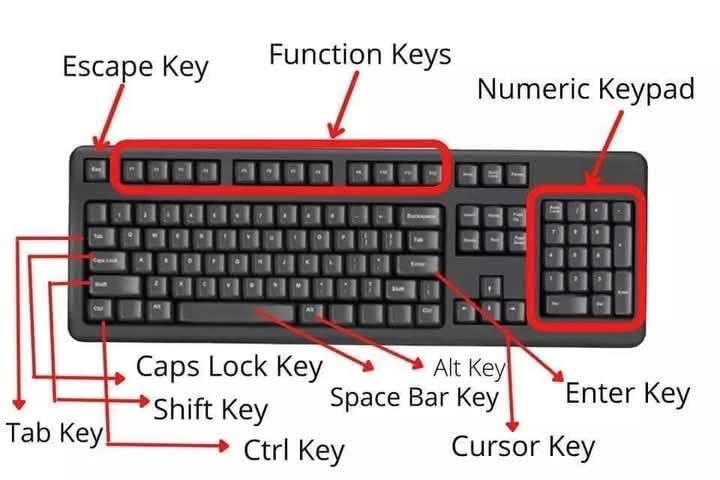

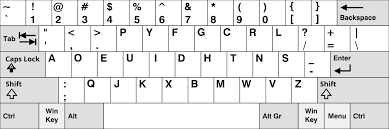

Why Is the Keyboard Not Arranged in Alphabetical Order?

The first lie most of us were told about intelligence is that order equals logic. Alphabetical order feels natural. It feels fair. It feels like how things should be. Yet every day, billions of people place their fingers on a keyboard that openly defies the alphabet without question.

A, B, C never stood a chance. Instead, we accepted QWERTY as normal, memorized its chaos, and built entire careers around it. The real story of why the keyboard is not alphabetical is not about convenience or design elegance.

It is about machines that kept breaking, decisions made under pressure, and how one workaround quietly shaped modern communication forever.

The Alphabet Was Never the Goal

When early inventors worked on typing machines in the 19th century, they were not trying to make writing easier for humans. Their concern was mechanical survival. The earliest typewriters used metal type bars that swung upward to strike ink onto paper.

Each letter had a physical arm. When two commonly used letters were placed too close together and typed in quick succession, those arms would collide and jam.

Alphabetical layouts made this problem worse.

English has predictable patterns. Letters like T and H or E and R appear together constantly. On an alphabetical keyboard, these letters sat side by side.

The faster a typist became, the more frequently the machine failed. Jams slowed work, damaged equipment, and frustrated users. The problem was not user error. It was structural.

Designers quickly realized that the alphabet was mechanically dangerous.

So the goal shifted. Instead of logical order, inventors prioritized separation. Letters that appeared together in common words were deliberately pushed apart.

This forced typists to slow down just enough to keep the machine functional. The keyboard became less intuitive, but the machine became usable.

In this moment, alphabetical logic lost to mechanical necessity.

How QWERTY Was Engineered to Be Awkward

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Christopher Latham Sholes, one of the key figures behind the modern typewriter, did not accidentally scramble the keyboard. The QWERTY layout was carefully constructed through trial and error. Early prototypes went through multiple revisions as engineers studied which keys caused jams most often.

The solution was counterintuitive. Instead of grouping similar letters, they scattered them.

This is why:

Frequently paired letters were separated

Typing rhythms were intentionally disrupted

Certain keys were harder to reach on purpose

The keyboard was designed to introduce friction.

Contrary to popular myth, QWERTY was not created to slow typists for productivity control. It was created to keep machines from destroying themselves. Speed was sacrificed for reliability. Once this layout proved stable, it gained commercial backing.

In 1873, Remington, a major manufacturer, adopted the QWERTY layout. That decision mattered more than any design principle. Once typewriters entered offices, schools, and newsrooms, muscle memory became currency. Typists trained for months. Businesses standardized equipment. Changing the layout now meant retraining an entire workforce.

The keyboard stopped being a tool and became an institution.

The Moment Alphabetical Keyboards Failed

Alphabetical keyboards did not disappear quietly. They were tested repeatedly. Educators proposed them as beginner friendly alternatives. Early calculators experimented with them. Some teaching devices even used alphabetical layouts for children.

But data did not lie.

Alphabetical keyboards performed poorly in real typing conditions. Studies and practical tests showed that they:

Increased finger travel

Reduced hand alternation

Slowed experienced typists significantly

Increased physical fatigue over time

Typing is not about knowing letters. It is about rhythm, flow, and motor efficiency. Alphabetical order ignores how language actually works. It treats letters as isolated units rather than part of predictable patterns.

In professional environments, alphabetical keyboards simply could not compete.

Once speed, accuracy, and endurance were measured, alphabetical layouts lost every serious test. Efficiency favored layouts designed around language frequency, not childhood learning tools.

Better Systems Existed but Timing Won

By the 1930s, researchers had already identified flaws in QWERTY. The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard was developed using studies of English letter frequency, finger strength, and hand balance. It reduced finger movement dramatically and increased typing comfort.

Colemak and other modern layouts followed similar principles decades later.

From a purely scientific perspective, QWERTY is inefficient.

So why did nothing change?

The answer is not ignorance. It is economics.

By the time better layouts appeared:

Millions of typists were already trained

Employers valued compatibility over improvement

Hardware manufacturers avoided fragmentation

Software defaults reinforced QWERTY dominance

Switching layouts required collective action. No single institution could force it globally. The cost of transition outweighed the benefits for most organizations. People adapted to inefficiency because it was familiar.

QWERTY survived not because it was the best, but because it arrived first and scaled fast.

The Keyboard as a Lesson in Technological Inertia

The modern keyboard is a fossil. It carries the imprint of a mechanical problem that no longer exists. Computers do not jam. Touchscreens have no moving parts. Voice input bypasses keys entirely.

Yet the same 19th century layout governs emails, codebases, social media, and global communication.

This persistence reveals something deeper about technology adoption.

Once humans internalize a system, logic becomes secondary. Muscle memory is powerful. Infrastructure resists change. What begins as a workaround can quietly become law.

The keyboard is not alphabetical because efficiency is contextual, not intuitive. It was built for machines before it was refined for humans. And once society synchronized around it, the cost of correction became too high.

Every time your fingers search for letters that should logically sit together but do not, you are touching a decision made to protect fragile metal arms over 150 years ago.

The alphabet lost. History won.

And we kept typing anyway.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

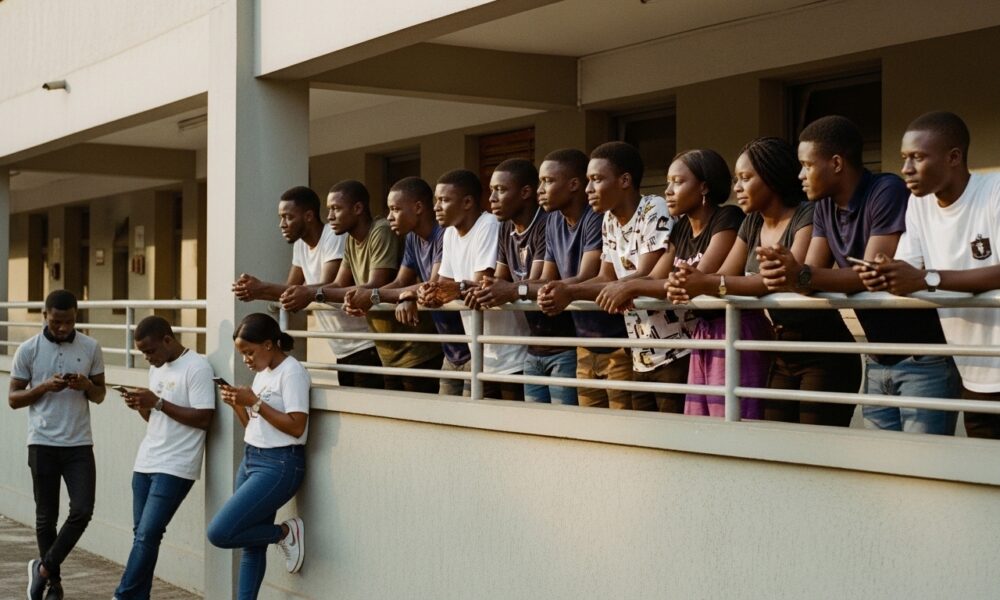

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...