How Many Mudashiru Ayenis Have We Buried, Or Tagged As "Mad"?

If Mudashiru Ayeni had been a white man with the same invention in 1971, tinkering in a dorm room, building what might politely be called a primitive robot assistant, his name would almost certainly be in the Guinness World Records, his story told in tech museums, and his photograph on posters in engineering schools.

He would be lionised as a visionary ahead of his time. But because he was a young Nigerian in a world that did not know how to see genius outside Western capitals, his brilliance was met with suspicion, not celebration, and a nation lost a chance to honour one of its earliest sparks of innovation.

This isn’t a fairy tale. What we do know, drawn from lived experience, collective memory, and what little remains documented, is about the raw hurt of being misunderstood, dismissed, and erased.

And beneath the surface of the Mudashiru Ayeni story lies a deeper wound at the heart of African innovation: a culture that too often looks down on its own achievements while celebrating the same accomplishments abroad.

The Unseen Inventor: When Curiosity Becomes a Curse

Walk with me as I picture a young Nigerian man in 1971, passionate about machines and the possibilities of intelligence written in wires and switches.

In an era when even the term “artificial intelligence” was on the lips of only the most daring technologists in the world, he built a battery‑powered machine that could respond to button presses with basic answers, an office assistant long before personal computers were common in Lagos offices or university labs.

For most of human history, those who dared to push boundaries were regarded with awe. But in Nigeria of the early 1970s, where the line between technical ingenuity and eccentricity was thin, and ignorance was deep, his invention was seen as odd, strange, and dangerous.

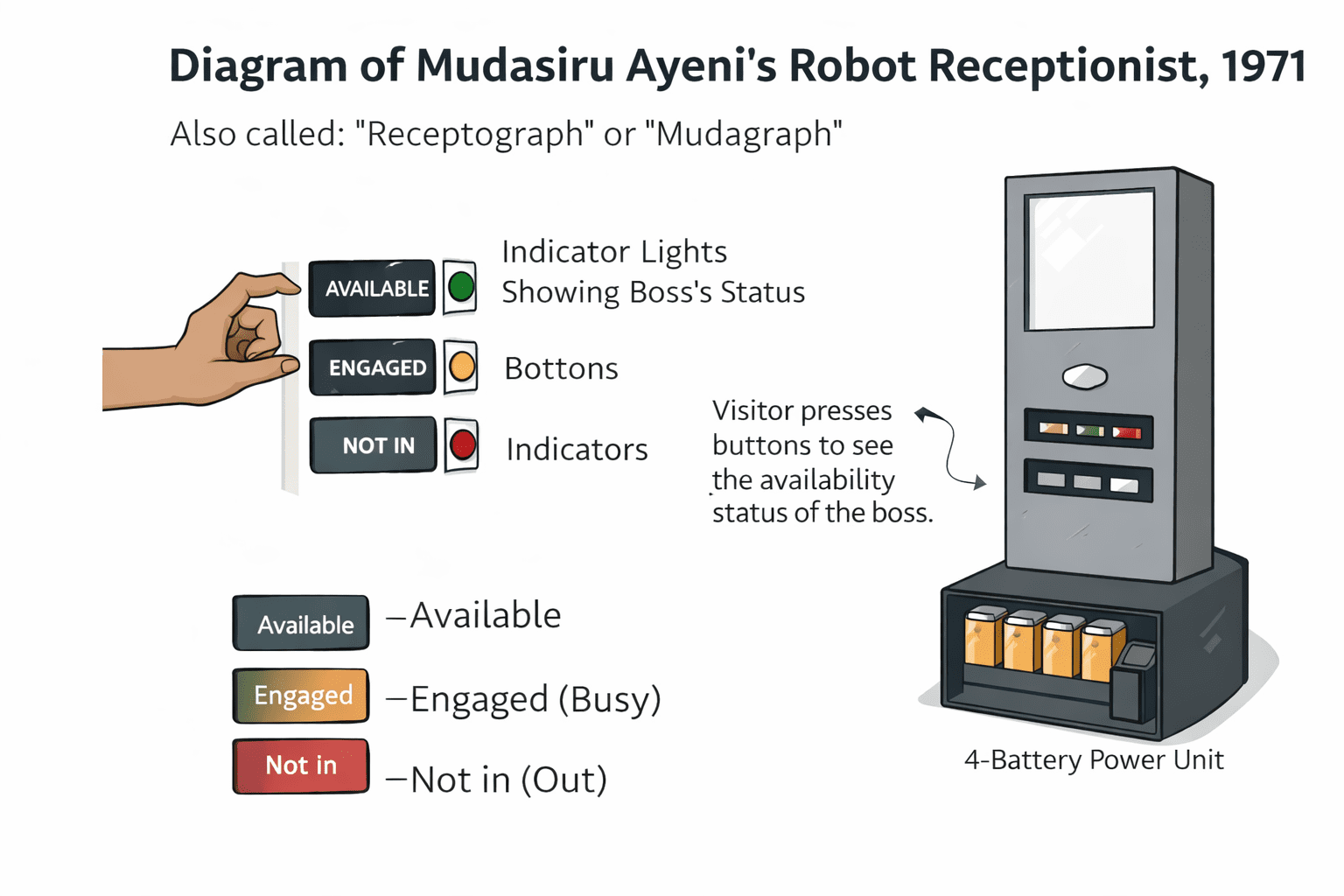

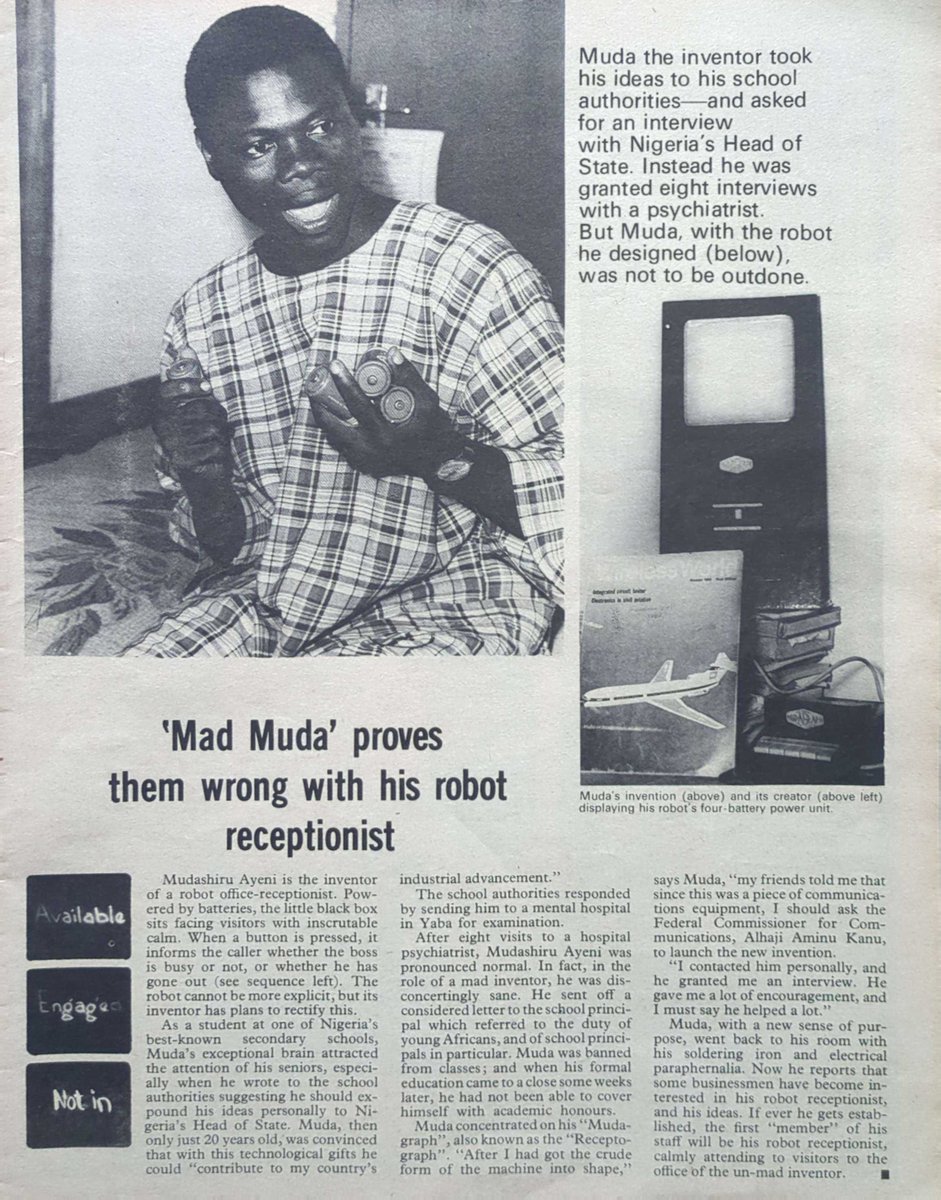

This is what actually happened: Mudashiru Ayeni, a young Nigerian student in the early 1970s, invented a battery-powered automated office device he called the “Muda-graph” or “Receptograph.” The machine functioned as a simple robot receptionist: when a visitor pressed a button, it indicated whether the boss was available, engaged, or not in.

Confident in his technological ability, Ayeni wrote to his school authorities requesting permission to present his ideas directly to Nigeria’s Head of State. Instead of supporting him, the school referred him to a psychiatric hospital for evaluation. After eight visits, psychiatrists declared him mentally sound. But the harm had already been done.

He was banned from classes. His education stalled. He left school without distinction, without honours, without the institutional backing that might have protected him. Nigeria had diagnosed curiosity as a problem.

Despite being banned from class and finishing school without academic distinction, Ayeni continued developing his invention. He later secured encouragement from Aminu Kano, who was Federal Commissioner for Communications at the time. Eventually, some businessmen expressed interest in his robot receptionist. Yeah, he started to see light at the end of the tunnel.

And that’s the end. No follow-up articles, no records of him being praised for his invention, no later interviews. There isn’t even an obituary or a biography. Just like that, his name, Mudashiru Ayeni, disappears.

His name only appears in scanned pictures of magazines.

It is impossible to measure exactly what he felt during those long days in that cold institution: the isolation, the shame, the confusion, but we can imagine the loneliness of a mind that had seen farther than those around him.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Pause for a moment: What does it do to a young man to be treated like his imagination was a symptom of sickness?

The Pain of Being Too Early, and Too African

There is a particular kind of ache that comes from being ahead of your time, and then having your own culture look at your breakthrough with scepticism instead of pride.

Look at how we speak about African achievements: Often, we wait for others to validate them. If a Nigerian engineer develops a technology that works, the headlines say “Inspired by a Scientist in the UK.”

If a Tanzanian filmmaker wins an award, the first question is, “Who else has won this before?”Do we ever pause long enough to just celebrate the win itself.

Now, how do you think Ayeni felt? He was a young man pushing the bounds of technology in a period when the world was just figuring out how to program mainframes.

In the United States and Europe, computer scientists were building the first rudimentary AI programs. Nigeria, still grappling with post‑independence challenges, had no dedicated research infrastructure for computing. Yet he saw possibilities where others saw oddity.

And when those around him recoiled, not out of malice, but out of ignorance and fear, he was left with a unique kind of heartbreak: the realisation that brilliance does not always find fertile ground in the soil where it is born.

This is the central tragedy of many African innovators: We too often fail to nurture genius from within, instead applauding it only after it is recognised abroad.

We ask our own to prove themselves time and again, to justify their dreams to people who already decided dreams like theirs are suspicious.

There is no official documentation of Ayeni’s invention in Nigeria’s archives, no academic paper preserved in a library, no patent filed in a government registry. But the story persists, whispered in tech circles and recycled in social media posts, because the pain it speaks to is real; the pain of brilliance dismissed.

A Mirror to Our Collective Insecurity

If you read the threads where this story is shared today, what you notice isn’t just fascination with the machine, it’s bitterness. It’s a collective wound.

The bitterness comes from asking a painful question: How many Mudashiru Ayenis did we lose because we didn’t believe in them?

When Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie talks about the danger of a single story, she points to what happens when a culture allows one narrative to dominate all others.

“Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.” — Chimamanda

The Mudashiru Ayeni story, unverified as it might be, becomes a metaphor for a broader truth: Africa doesn’t always treasure its own narratives until the world does first.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Hold on: Its not even that complicated. Ayeni might have dreamt of being a world-renowned scientist, or maybe he wanted to be the first black man to build the first African robot, not the one we see on TV with a metal body and an automated “Hey Siri” voice.

But an actual robot with black African skin. Guess we will never know. We can only imagine, but as for owning the narrative of who Ayeni could have been? It lies deep within our hearts.

Look at our headlines: We celebrate African tech only when foreign investors pour money into it. We centre African art only when Western galleries buy it. We fixate on African suffering, but too rarely pause to spotlight African innovation unless global media has already done so.

And so what does this do to young African minds today? It teaches them that brilliance must seek validation abroad. That dreamers must become asylum seekers for their own ideas. That genius must wear a passport stamped by the West to be taken seriously.

It is no wonder that so many young talents leave, not because they don’t love their home, but because they believe the world outside will see them more clearly than the people among whom they were born.

What It Would Mean If We Finally Saw Ourselves

Can we just have a Nigeria where the story of someone like Mudashiru Ayeni didn’t end in a psychiatric ward or a whisper online? I can’t stop thinking if what would have happened if his work had been documented, shared, and celebrated.

So what if, instead of ridicule, he found mentors, funding, and preservation.

Imagine a society that looks at its thinkers and says: We believe you. We will build with you. We will carry your name forward.

Such a change would not just honour a single inventor, it would transform a culture’s relationship with innovation itself.

Because the greatest tragedy in the Ayeni story isn’t that technology failed. It’s that a nation failed one of its own before the world even had a chance to recognise him.

If history ultimately records nothing about Mudashiru Ayeni beyond a few forum posts, then that record will tell us something profound, not about his abilities, but about our collective blindness.

Perhaps the most important question we should ask today is not whether he built a robot, but whether we as a society are willing to believe in brilliance before it is validated elsewhere.

If we remain incapable of that, then for every Mudashiru Ayeni lost in the archives of silence, there will be many more waiting in the shadows, their voices unheard, their potential unfulfilled.

And that would be the hardest loss of all.

More Articles from this Publisher

How Many Mudashiru Ayenis Have We Buried, Or Tagged As "Mad"?

He built a robot at 20. Instead of applause, Nigeria sent him to psychiatrists. This is the story of Mudashiru Ayeni, th...

7 Countries Where Valentine’s Day Isn’t February 14

Valentine’s Day isn’t always February 14. Some countries mark love on entirely different dates, and the traditions behin...

Countries That Have Restricted Valentine’s Day Celebration

Valentine’s Day is global but not universally accepted. In some countries, February 14 has been restricted, discouraged,...

What Exactly Is an African Man’s Business with Valentine?

Every February 14, love becomes loud, red and expensive. But what exactly is an African man’s business with Valentine’s ...

9 Ways to Survive Valentine’s Day As A Singlet

Single on Valentine’s Day? Forget the roses and rom-coms; here’s your perfect survival guide to survive the day and cele...

Africa’s Most Inefficient Industries, And Why They’re the Biggest Opportunities

Africa’s biggest opportunities aren’t in flashy tech; they’re in the messiest, slowest, most frustrating systems. Learn ...

You may also like...

Shockwave in Transfers: Manchester United Reportedly Eyeing Liverpool Midfield Maestro Mac Allister!

Football's summer transfer window is heating up with major European clubs eyeing key players. Manchester United is repor...

Klopp's Agent Drops Bombshell: Two Premier League Giants Vied for Jurgen Post-Liverpool Exit!

)

Jürgen Klopp's agent, Marc Kosicke, revealed that Chelsea and Manchester United pursued the German manager after his Liv...

Tom Hardy's Crime Saga Hits New Heights: Fans Rave Over Season 2 and Stellar Performance

Emmett J. Scanlan teases an "insane" Season 2 for Guy Ritchie's 'MobLand', promising heightened drama and the return of ...

Game of Thrones Spinoff 'A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms' Stirs Controversy and Celebration

<i>A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms</i> Episode 5, "In the Name of the Mother," earns accolades as the franchise's highest...

'The Rookie' Star Eric Winter on Why He Loves Chenford's Unpredictable Journey

The Rookie Season 8 sees Tim Bradford embrace his new watch commander role, facing managerial challenges while his roman...

Sarah Ferguson's Business Empire Collapses Amid New Epstein Scandal Revelations

Six businesses associated with Sarah Ferguson, the former Duchess of York, are being dissolved amid heightened scrutiny ...

Chaos at JKIA: Aviation Workers' Strike Grounds Flights, Stranding Thousands

Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi faced widespread chaos, delays, and flight cancellations as aviation work...

Outrage Erupts After Tragic Kitengela Rally Shooting, Family Demands Justice

Tragedy struck an ODM 'Linda Mwananchi' rally in Kitengela as 28-year-old Vincent Ayomo Otieno was fatally shot, alleged...