Was Santa Claus Really Copied from African Masquerades?

If a red suited man who flies across the sky can be accepted without question, why does a masked ancestral figure rooted in centuries of African cosmology provoke fear, doubt, or dismissal?

I came across a comment while scrolling through an article that was posted on Naira land on the 20 year old inventor that was sent to a psychiatric hospital. The response wasn’t curiosity. It wasn’t even disagreement. It was mockery.

And that difference isn’t random.

It’s not about who is smart. It’s not about who is ignorant. It’s about who decides which beliefs are normal and which ones must be laughed at.

Before we start shouting, let’s be clear about what we’re really dealing with: history, culture, and who has been in charge of the story for a long time.

The Historical Roots of Santa and the Myth of Theft

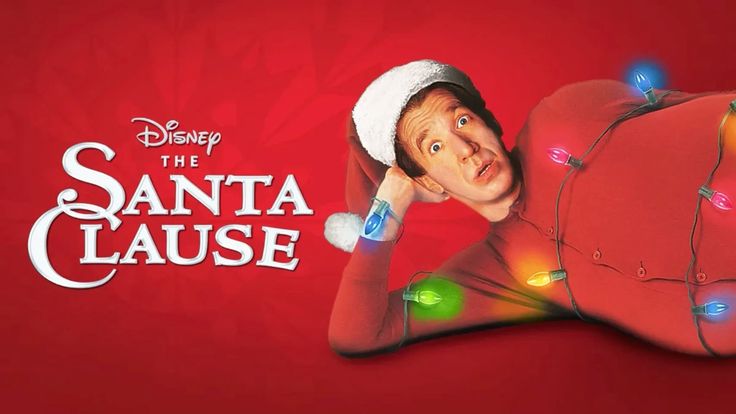

When you think of Santa Claus, this is the figure you usually have in mind: an older, white-haired, bearded and chubby man in a red and white fur suit.

But why has this image become so popular and who invented the character in the first place? Although it is a widespread myth, Coca-Cola did not create Santa Claus, but shaped his modern image and spread it further.

The modern Santa Claus did not descend from West African masquerade traditions. His origins trace back to Saint Nicholas, a fourth century Christian bishop from Myra in present day Turkey.

Over centuries, European folklore reshaped this figure. In the nineteenth century, writers in the United States popularized a jolly, gift bearing version of him.

According to Coca-Cola, the illustrator Haddon Sundblom, who was commissioned by the company, coined the image of a warm-hearted, corpulent man in a red and white coat from 1931, using Clement Clark Moore's 1823 poem "A Visit From St. Nicholas" (commonly called "'Twas the Night Before Christmas").

This image, which was distributed internationally in advertisements and posters, subsequently became the standard visual version.

There is no credible historical line linking Egungun or Mmanwu to Santa Claus. Their origins, meanings, and religious foundations are different. Saying one was stolen from the other sounds dramatic, but it doesn’t stand on evidence, and weak arguments weaken the point.

But rejecting theft doesn’t end the conversation.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

What happened wasn’t direct copying. It was ranking; one story was lifted while the other was pushed down.

European Christian folklore moved with ships, missionaries, colonial administrations, printing presses, and eventually Hollywood.

African spiritual systems did not travel under the same protection. In many places, they were labelled pagan, backward, or dangerous.

Santa expanded with empire, commerce, and global advertising.

Masquerade traditions stayed rooted in their communities, and were often preached against or outlawed.

That gap didn’t happen by coincidence.

Masquerade as Spiritual Infrastructure

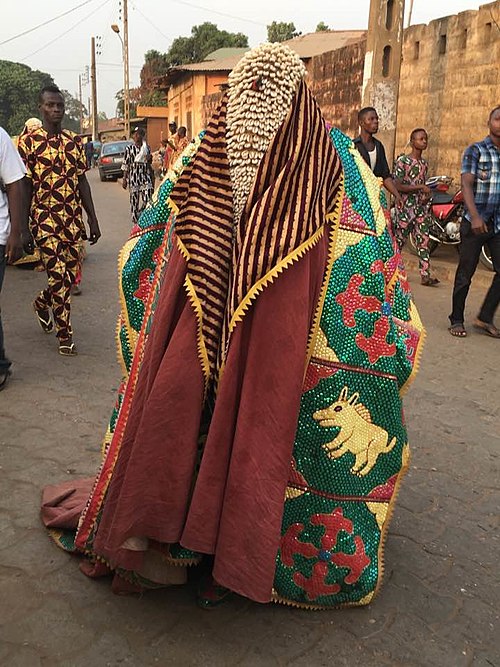

Across West Africa, masquerades are not fair y tale characters. They function as moral regulators, ancestral embodiments, and community institutions.

Among the Yoruba, the Egungun represents ancestral spirits returning to guide the living. Among the Igbo, Mmanwu can perform judicial, ritual, and communal functions. These traditions predate European contact by centuries.

They are embedded within lineage systems, metaphysical frameworks, and communal authority. They are not seasonal entertainment figures.

Yet in many modern African cities, a child is more likely to be told that Santa brings gifts than to be taught the philosophical depth of Egungun.

This is not stupidity. It is actually conditioning.

Colonial education systems replaced indigenous cosmologies with European religious instruction. Mission schools labelled local spiritual systems as pagan or demonic. Over time, a hierarchy formed inside the imagination.

European myth became harmless magic.

African spirituality became dangerous superstition.

The result is not simply religious conversion. It is epistemic displacement. One system is framed as cultural heritage. The other is framed as backwardness.

That hierarchy shapes how belief is distributed.

Cultural Hegemony and the Architecture of Belief

The Italian thinker Antonio Gramsci described cultural hegemony as the process by which dominant groups shape what is considered normal and civilized. Power does not only control armies. It controls legitimacy.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

When European expansion reshaped Africa, it did not need to erase every indigenous system physically. It needed to reposition them symbolically. Through church authority, state power, and later media export, European frameworks became defaults.

Santa is marketed as magic.

Masquerade is framed as fetish.

One appears in malls, cartoons, movies and global advertising.

The other appears in anthropological documentaries or cautionary sermons.

The disparity is not theological. It is structural.

This is where thinkers like Frantz Fanon become relevant. Fanon wrote about internalized colonialism, about how colonized societies can absorb narratives of inferiority.

When a child grows up seeing Western symbols celebrated in school plays and African symbols ridiculed in sermons, the mind organizes value accordingly.

Over time, external validation becomes the measure of truth.

It is not that Africans are incapable of believing in their own systems. Many communities continue to protect and practice masquerade traditions with seriousness and reverence.

Global power decides which stories are universal and which are local curiosities.

Symbolic Hierarchy and the Politics of Legitimacy

The real issue is not Santa versus Egungun,it is symbolic hierarchy.

Why does one circulate as harmless fantasy while the other is often portrayed as primitive? Why does one attract corporate sponsorship while the other invites suspicion?

Because power precedes belief.

Educational curricula, religious institutions, and media ecosystems shape imagination. When those institutions are influenced heavily by external frameworks, the imagination of children reflects that influence.

A child in Lagos accepts Santa easily not because the child is foolish, but because Santa arrives through cartoons, Christmas decorations, school plays, and global marketing. Egungun often arrives through whispered caution or religious warning.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Narrative legitimacy is institutionally produced.

If African cosmologies were taught with academic rigor, presented without ridicule, and amplified through film, literature, and commercial media at the same scale as Western folklore, belief patterns would shift. Not necessarily toward worship, but toward respect.

This does not require rejecting Christianity or Islam. It requires refusing symbolic inferiority.

The danger is not in believing in Santa. The danger is in unconsciously absorbing a hierarchy where foreign myth is culture and indigenous cosmology is superstition.

Historical precision strengthens this argument. Santa was not stolen from masquerade systems. But masquerade systems were displaced in prestige by institutions backed by imperial power.

The deeper question is who decides which narratives deserve dignity.

When belief systems travel with economic dominance, military power, and media saturation, they become normalized. When belief systems are confined to marginalized spaces, they become exoticized or demonized.

Until African epistemologies are treated as intellectual frameworks rather than cultural relics, the imbalance will persist.

Children believe what their environment authorizes.

If the environment authorizes Western folklore as universal and African cosmology as suspect, the hierarchy sustains itself.

Changing that requires more than outrage. It requires institutional redesign. It requires curriculum reform. It requires media investment.

It requires intellectual honesty that neither romanticizes nor demonizes tradition.

Power shapes imagination. Imagination shapes belief. Belief shapes identity.

The question is not whether Santa exists.

The question is whether African narratives will ever receive equal legitimacy in the architecture of the modern mind.

You may also like...

Football World Erupts: Vinicius Jr. Racism Row Ignites Calls for Lifetime Ban

)

Kylian Mbappé has called for a lifetime ban for a Benfica player accused of racially abusing Vinícius Jr during a Champi...

Colbert Blasts CBS Over Blocked Interview, Cites Network's FCC Fears

Stephen Colbert publicly challenged CBS for barring an interview with Texas Rep. James Talarico, citing preemptive netwo...

Paramount Sale Heats Up: Rival Suitor Talks, Misinformation Claims Rock Industry

A fierce takeover battle for Warner Bros. Discovery is unfolding, with Netflix and Paramount Skydance vying for control....

A Giant's Legacy: Civil Rights Icon & Grammy Winner Rev. Jesse Jackson Passes Away at 84

Reverend Jesse Jackson, a pivotal figure in American civil rights and politics, has died at 84 after a battle with a neu...

Bad Bunny's Unprecedented Latin Chart Takeover: Makes History With Top 25 Clean Sweep!

Bad Bunny achieves a historic sweep across Billboard charts, setting a new record with 29 simultaneous titles on Hot Lat...

Benedict Umeozor's Academic Marvel: The Path to a Perfect 5.00 CGPA at University of Lagos

Discover the meticulous strategies and unwavering commitment that led Benedict Umeozor to achieve a perfect 5.0 CGPA. Th...

Football Explodes! NFF Fights FIFA Verdict in Nigeria-DR Congo Dispute!

The Nigeria Football Federation has debunked claims of a FIFA verdict regarding its protest against the Democratic Repub...

AU Declares Samia Suluhu Hassan: A Champion for Africa!

President Samia Suluhu Hassan has been appointed as the AU Champion for reproductive, maternal and child health, a role ...