Thebe Medupe and Africa’s Astronomical Heritage: Mapping the Stars Through Science and Story

While ancient African astronomy was traditionally preserved through oral history, ritual, and architecture rather than credited to individual astronomers, Dr. Thebe Medupe, a modern South African astrophysicist, has become a defining voice in recovering and celebrating the continent’s vast celestial legacy. His career connects the ancient and the modern, blending indigenous African sky knowledge with cutting-edge astrophysics to tell a fuller story of Africa's scientific contributions.

Ancient African Astronomy: A Legacy in the Stars

Long before telescopes, Africans studied the night sky with profound insight. Astronomy in Africa was a collective cultural achievement, deeply interwoven with timekeeping, agriculture, navigation, and spiritual life.

Key Uses of Astronomy in Ancient Africa

Timekeeping and Seasonal Cycles: Communities like the Nilotic peoples of East Africa aligned their calendars with the heliacal rising of Sirius, which foretold the annual flooding of the Nile, critical for agriculture

Navigation: Nomadic and pastoral groups, especially in the Sahara and Sahel, used star constellations to orient themselves across vast, featureless terrains (Royal Museums Greenwich).

Cultural and Ritual Timing: Lunar and stellar cycles marked planting seasons, fertility festivals, and ancestral rituals. The Khoisan of southern Africa, for instance, told stories linking the Pleiades to the arrival of rain (South African Journal of Science).

Monuments to the Stars: Ancient Astronomical Sites

Nabta Playa, Egypt

Located in southern Egypt, Nabta Playa is one of the world’s oldest known astronomical sites, situated in the Nubian Desert approximately 100 kilometers west of Abu Simbel. Dating back more than 7,000 years—predating Stonehenge by nearly 2,000 years—this prehistoric site contains a complex array of megalithic structures, stone circles, and burial mounds created by nomadic pastoralists.

The most striking feature of Nabta Playa is a stone circle believed to function as a calendar device, with several stones aligned to mark the summer solstice sunrise. Scholars have proposed that some of these megaliths also align with Orion’s Belt, a significant constellation in both ancient Egyptian cosmology and indigenous African sky lore. These alignments suggest a sophisticated understanding of astronomical phenomena, possibly used to predict seasonal changes, plan ceremonial events, and coordinate cattle migrations and rainy-season survival strategies.

Excavations by archaeologist Fred Wendorf and astronomer Thomas Brophy have uncovered ceramic artifacts, burial tumuli, and evidence of ritual activity, indicating that Nabta Playa was not just a practical tool for timekeeping but also a sacred site for early religious or cosmological practices. Its builders are believed to have influenced later developments in Pharaonic Egypt, including their solar and stellar cults.

Today, Nabta Playa stands as a monument to prehistoric African innovation, challenging the idea that advanced science and astronomy began only with Western civilizations.

Great Zimbabwe

An image showing what the Great Zimbabwe looked like in 1350

An image showing what it looks like now

In Great Zimbabwe, the monumental stone city built between the 11th and 15th centuries, the iconic soapstone birds have sparked deep historical and symbolic interest. These carved figures, perched atop tall monoliths, are believed by some scholars to represent celestial totems or ancestral spirits, possibly tied to sky worship or astronomical symbolism (British Museum – Soapstone Bird). Though the exact meaning remains contested, there are compelling theories suggesting that parts of the city's architectural layout may align with cardinal directions and solar events such as the solstices.

Built by the Shona people, Great Zimbabwe is a remarkable testament to precolonial African engineering, urban planning, and cultural sophistication. Some archaeologists have proposed that the Great Enclosure, with its massive dry stone walls and mysterious conical tower, may have served not only political or ceremonial purposes but also acted as a cosmic compass, aligning with the seasonal movement of the sun

While definitive astronomical interpretations are still being studied, the possibility that Great Zimbabwe encoded celestial knowledge reinforces the idea that ancient Africans were deeply observant of the natural and cosmic world, not just as a spiritual domain but as a scientific guide for agriculture, rituals, and governance.

The Dogon and Sirius

The Dogon people of Mali are renowned for their intricate oral traditions and cosmological knowledge, particularly regarding the star system Sirius. According to Dogon mythology, Sirius (Sigi Tolo) is accompanied by a dense, invisible companion star, known as Po Tolo, which modern science identifies as Sirius B, a white dwarf star that orbits Sirius A. Remarkably, Sirius B was only officially confirmed by Western astronomers in the 19th century, using telescopic and spectroscopic technology.

Some scholars and researchers argue that the Dogon may have had advanced astronomical knowledge about Sirius B’s existence, orbital period, and even its invisibility to the naked eye, long before it was documented in Western science. This possibility was famously popularized in the 1970s by French anthropologists Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, who claimed the Dogon knew Sirius B had a 50-year elliptical orbit, matching modern measurements.

Thebe Medupe: Africa’s Modern Stargazer

Born in 1973 in Mafikeng, South Africa, Thebe Medupe grew up in a modest rural village where electricity was often unavailable. But those nights offered something extraordinary: a pristine, unpolluted view of the night sky. It was here, beneath these vast cosmic canvases, that Medupe’s love for astronomy was born.

At just 13 years old, a once-in-a-lifetime celestial event transformed his curiosity into passion. When Halley’s Comet passed Earth in 1986, he watched it with wonder, not through a telescope, but with the naked eye and a deep hunger for understanding. Determined to explore further, he ingeniously built his telescope using cardboard tubes and lenses, an act that foreshadowed a future career in world-class astronomy.

Academic Journey

Medupe’s academic path led him to the University of Cape Town, where he pursued physics and went on to earn a Ph.D. in astrophysics. His research focused on stellar atmospheres and pulsations — a field concerned with how stars vibrate and evolve internally. These are not just esoteric concepts; they help explain how stars are born, live, and eventually die.

After completing his doctorate, Medupe broke barriers by becoming one of South Africa’s first Black astrophysicists. He took on key leadership roles, including chairing the National Astrophysics and Space Science Programme (NASSP), a collaborative initiative aimed at building a skilled astronomical community across Africa. He also became an executive in the African Astronomical Society (AfAS), helping shape the continent’s scientific future.

Cosmic Africa: Reconnecting Science and Culture

In 2002, Medupe directed and starred in the documentary Cosmic Africa — a groundbreaking project that took him on a journey through Egypt, Namibia, Mali, and South Africa. In the film, he engages with elders, rituals, and local sky traditions that reveal how deeply African communities have observed and interpreted the stars for thousands of years.

The documentary doesn’t just celebrate ancient knowledge — it challenges the Western narrative that views science as a purely European endeavor. Instead, it frames African cosmology as systematic, empirical, and logical, rooted in close observation of natural phenomena.

“Our ancestors weren’t just storytelling romantics,” Medupe explains in the film. “They were keen observers of natural patterns.”

Through this lens, Cosmic Africa becomes both a scientific exploration and a cultural reclamation, offering African audiences a new way to see themselves as inheritors of a rich scientific tradition.

The Timbuktu Manuscripts: Astronomy on Paper

While much of Africa’s astronomical heritage is preserved through oral tradition, Medupe also turned his attention to written sources, particularly the Timbuktu manuscripts. These centuries-old texts, many of which date from the 13th to 17th centuries, are written in Arabic and African languages, and contain diagrams of the stars, planetary motion charts, and notes on eclipses and calendar systems.

With support from preservation and research bodies, Medupe helped digitize and study these fragile documents. His work proved that African scholars were writing about astronomy in a sophisticated manner at a time when much of Europe was still emerging from the medieval period. These manuscripts offer evidence of a structured, scholarly tradition in African astronomy that goes beyond oral narratives.

Global Impact and Inspiration

Medupe’s influence extends far beyond his research. He is passionate about science education, especially in underserved communities. Through public lectures, curriculum reform, and mentorship programs, he has inspired hundreds of students across Africa to pursue careers in science. His efforts were profiled in the journal Astronomy & Society, where he emphasized the importance of connecting science to identity and culture.

He also contributes actively to academic research, particularly in the field of stellar pulsations — work that has been published in leading journals like The Astrophysical Journal and used in developing better models of how stars function.

Just as importantly, Medupe has helped Africans — especially young people — reclaim their place in the story of science. He argues that understanding traditional African astronomy allows youth to see that science is not a foreign concept imposed from outside, but a field their ancestors actively contributed to.

Conclusion: A Legacy Written in the Stars

Thebe Medupe stands as a bridge between the ancient stargazers of Africa and the modern astrophysicists shaping the future. While Western science often overlooks African contributions to astronomy, Medupe’s life and work reveal a vibrant, often hidden history — one where African societies not only observed the cosmos, but built knowledge systems around it.

By merging ancestral sky wisdom with the tools of modern astrophysics, Medupe is ensuring that Africa is not just a footnote in scientific history but a thriving voice in its ongoing evolution.

Though some experts question the accuracy and interpretation of these findings, suggesting cultural contamination or miscommunication during fieldwork, the Dogon’s rich sky lore continues to intrigue astronomers, anthropologists, and skeptics alike. Whether myth or misunderstood memory, the story of Po Tolo challenges assumptions about the limits of indigenous African knowledge systems and their potential astronomical depth.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

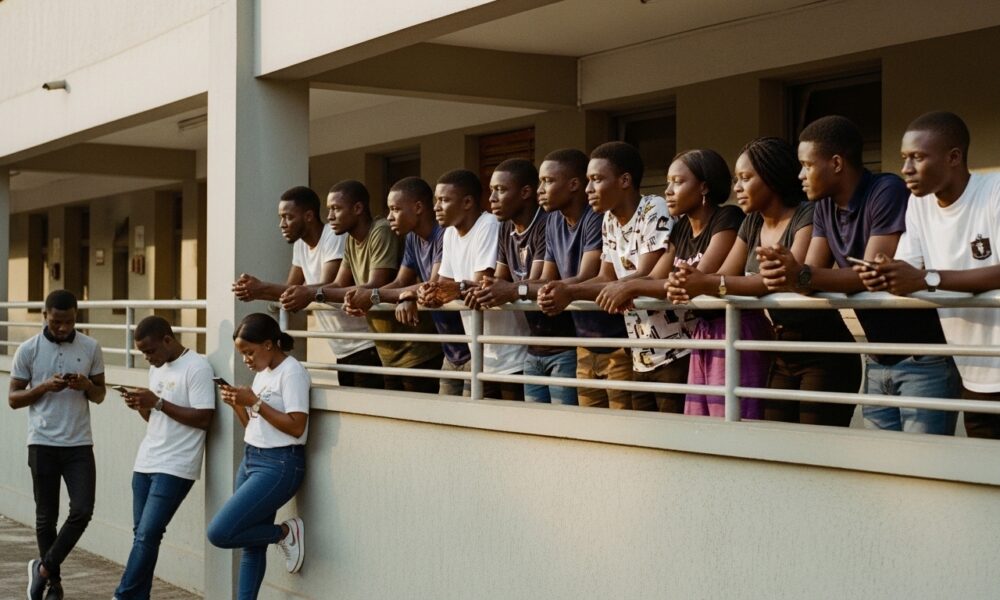

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...