The Strange African Myths That Still Live Today

There are stories whose teeth never dull. Passed down beside cooking fires, whispered across river crossings, sung into the roots of ancient trees; these myths don't belong only to the past. They live in the way people name storms, treat the sick, make art, and warn their children. Below are seven of the strangest African myths that still pulse through the continent today; not as quaint curiosities but as living, changing forces that shape behavior, belief and culture.

1. Mami Wata — the irresistible water spirit that travels and transforms

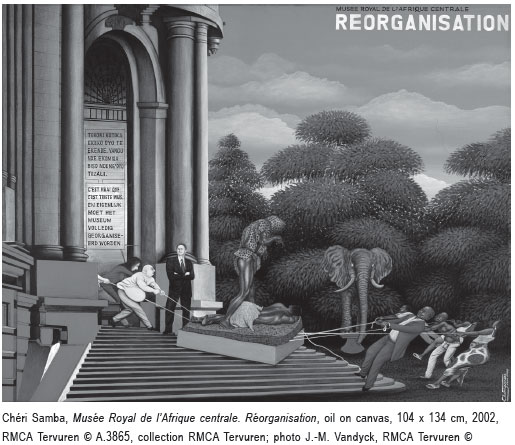

Walk the markets of West and Central Africa, or step into an African art museum, and you’ll find Mami Wata’s face: a woman half-water, half-mystery, combing her hair in a mirror. Mami Wata is not a single goddess but a syncretic family of water spirits whose forms and meanings shift with time and place.

She can be a seductress who lures traders and fishermen, a protector who blesses healers and merchants, or a jealous force demanding offerings and fidelity. Her iconography; long hair, a mirror, sometimes a mermaid tail, absorbs influences from European mermaids, Indian deities, and local water traditions.

That pliability is her power: as communities changed under trade and colonization, Mami Wata adapted and expanded, becoming a transnational figure across West and Central Africa and their diasporas.

Today she appears in sculpture, high-fashion shoots, Pentecostal critiques, and shrine rooms; artists and curators point to her as proof that African religious life has long been porous, creative, and globally entangled.

2. Anansi — the trickster who crossed oceans and time

Anansi the spider is the compact, cunning storyteller of the Akan people of Ghana, a creature who survived slavery and the Middle Passage by changing costume.

In West Africa, Anansi is a trickster archetype: he is small but clever, stealing stories, besting larger animals, and teaching moral curiosities through mischief. When Akan people were captured and dispersed across the Caribbean and the Americas, Anansi went with them.

In the New World he became Anansi, and later echoes appear in Br’er Rabbit tales and other trickster figures. That migration of a character, oral, elastic, and mischievous, is one of the clearest examples of how African myth adapted to new worlds and remained relevant.

Modern novels, films, and pop culture (from children's books to blockbuster movies that invoke pan-African mythology) keep Anansi’s DNA alive: sly, teachable, and stubbornly instructive.

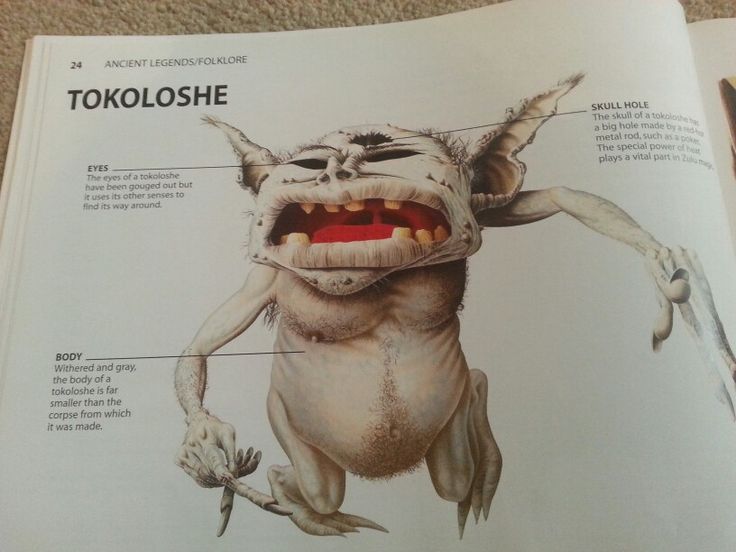

3. The Tokoloshe — the night visitor that reshapes behavior and health narratives

In southern Africa a small, mischievous, even vicious, creature creeps into conversations about sleep, mental illness and social anxieties: the tokoloshe (also spelled tikoloshe).

Described in many accounts as a short, hairy, sometimes sexually transgressive goblin, the tokoloshe is said to be conjured by witchcraft to harass enemies ; stealing, assaulting, or simply terrorizing people while they sleep.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

The belief can be deeply practical: in overcrowded urban townships people build beds on bricks to keep the tokoloshe out of reach, and accusations of tokoloshe activity can stand in for conflicts over land, jealousy, or social exclusion.

Contemporary research finds that tokoloshe narratives also intersect with mental-health experiences: sufferers and families sometimes frame nightmares, sleep paralysis, or psychosis through the tokoloshe lens, which affects help-seeking and community response. Whether one treats the tokoloshe as metaphor or monster, its sociocultural footprint is real, shaping homes, medicine, and social blame.

4. The Adze — a firefly that explains malaria and misfortune

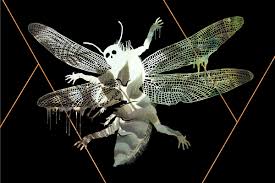

Among the Ewe people of Togo and Ghana lives a particularly eerie myth: the adze. In its insect form the adze is said to be a tiny winged thing, a firefly-like shape that slips through cracks to suck the blood of sleepers.

In human form the adze becomes a witch who possesses people, brings famine or illness, and creates suspicion within families. Anthropologists and historians read this story as a cultural response to airborne and insect-borne threats: the adze may once have been a way to explain the sudden deaths and fevers that came with malaria and other diseases, invisible killers that enter houses at night.

The tale also functions socially: labeling someone an “adze-host” can be a way of explaining envy, sudden wealth, or unexplained loss, and thus it polices social behavior and redistributes blame. Today the adze appears in journalism and online essays as a haunting example of how myth and disease-history entwine.

5. Leopard-men and the law of shadow justice

In parts of West and Central Africa, particularly during the colonial and early post-colonial years, tales circulated of leopard-men, secret societies whose members purportedly donned leopard skins and terrorized communities.

These groups were said to conduct ritual punishments that left victims mangled as if by a beast. Historians and anthropologists argue that these stories often reflect political resistance, secret policing, and the anxieties of times when formal law was absent or hostile to local customs. Leopard-society imagery traveled too: in the Americas, cults and diasporic secret societies carried similar symbol-languages.

Today the leopard-man myth persists less as literal practice and more as a narrative shorthand for hidden power, clandestine violence, and the uncanny blending of human and animal moral economies. Researchers caution against romanticizing these groups; in many cases, “leopard” stories were sewn into colonial court records, rumor networks, and struggles over land and law.

6. Sasabonsam — the forest enforcer who keeps nature in balance

From the Akan forests of West Africa comes the sasabonsam: a monstrous tree-dweller with iron teeth and hook-like feet that dangles from branches to punish trespassers.

Far from being a mere bogeyman, the sasabonsam embodies a rule: leave the forest alone some days, or respect ritual restrictions, and the land will renew itself. Anthropologists point out that such myths functioned as ecological taboos — cultural ways to conserve game, allow fallow cycles, or preserve spiritual sites.

Today Sasabonsam’s terrifying visage appears in travel essays and art pieces that reframe the creature as an early conservationist, a mythic guardian with blunt methods. In a time when deforestation and land disputes are urgent, these old stories offer a subtle reminder: myth and environmental stewardship were once the same conversation.

Why these myths survive

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Stories survive when they do work. These myths still live because they do at least three things:

They explain the unexplained. When medicine, science or the state failed to explain sudden death, disease, storms or missing children, myth stepped in with a narrative people could use. (Think adze and malaria; tokoloshe and sleep-related events.)

They teach social rules. Myths police behavior. The Ninki Nanka keeps children from swamps; Sasabonsam enforces forest rest days; Anansi models cunning (and the consequences of greed).

They adapt and travel. Myths that are porous — that absorb other cultures, trade goods, saints, or modern media — survive better. Mami Wata and Anansi are the poster children of cultural mobility: they change shape without losing story-cores.

Modern life, modern forms

These myths are not fossils. They reappear in plastic as souvenirs, as hashtags, in blockbuster nods, and in the moral panics of urban neighborhoods. A Mami Wata sculpture might hang in a Lagos gallery beside a Pentecostal critique, Anansi pops up in children’s books and Afro-futurist fiction, and tokoloshe stories influence how parents manage fear and how clinics address trauma and sleep disorders. Even treasure-hunting “dragon expeditions” and cryptid podcasts feed back into local economies and global imaginations, reframing old tales as modern attractions.

That mixture — reverence, reinvention, and occasionally exploitation — is the modern life of African myth. The stories survive not because we keep them frozen but because we keep retelling them for new reasons.

A final thought: believe, or learn the lessons anyway

It’s easy for an outsider to scoff at these myths. But to do so misses their function. Myths are shorthand: compact maps of social memory, environmental practice and moral imagination. Whether you treat the tokoloshe as a literal creature, an illness metaphor, or a social accusation, you must reckon with its effects — the bricks under the bed, the local healer consulted, the family torn by accusation. Whether Mami Wata is “real” matters less than the economies she shapes: healing businesses, artistic inspiration, shrine economies and the gentle choreography of gifts and demands.

These myths are, in short, still alive because people still need them — to explain, to warn, to protect, to remember. And as long as communities continue to narrate the edges of the known world, new myths will be born from old ones, each one strange, useful, and stubbornly persistent.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

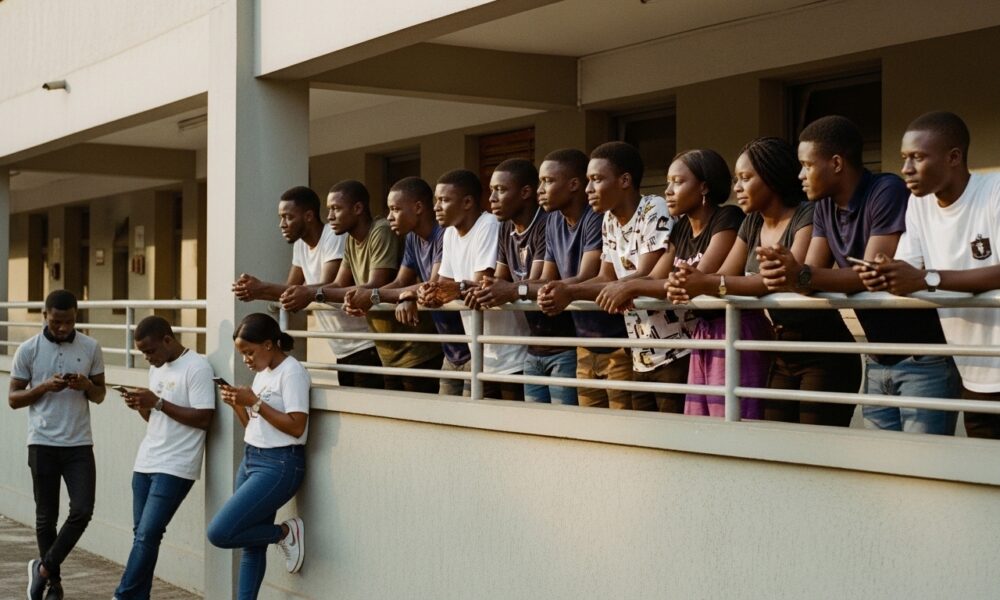

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...