How a “Wrong” Admission Helped Ifeoluwa Garba Tap Into a $45.15 Billion Industry

When Ifeoluwa Garba lost his chance to study Mechanical Engineering at the University of Ibadan, he assumed the opportunity had slipped away for good. What he did not realise was that his placement into Wood and Biomaterial Engineering would position him inside a global industry projected at $45.15 billion. That unexpected path led to Ecobag Mart, a student led venture converting waste grass and agricultural residue into durable, biodegradable paper bags.

At first, the change of course felt like a consolation prize. Wood and Biomaterial Engineering sounded unfamiliar and, to him, less glamorous than the mainstream engineering disciplines he had dreamt about in secondary school.

But as the semesters went by, laboratory sessions, field assignments, and hours spent poring over research articles slowly reshaped his perspective. He began to see that the discipline sat at the crossroads of sustainability, manufacturing, and material science, a place where small innovations could ripple outward into global supply chains and everyday consumer products.

From Campus Fair to Constant Pitching

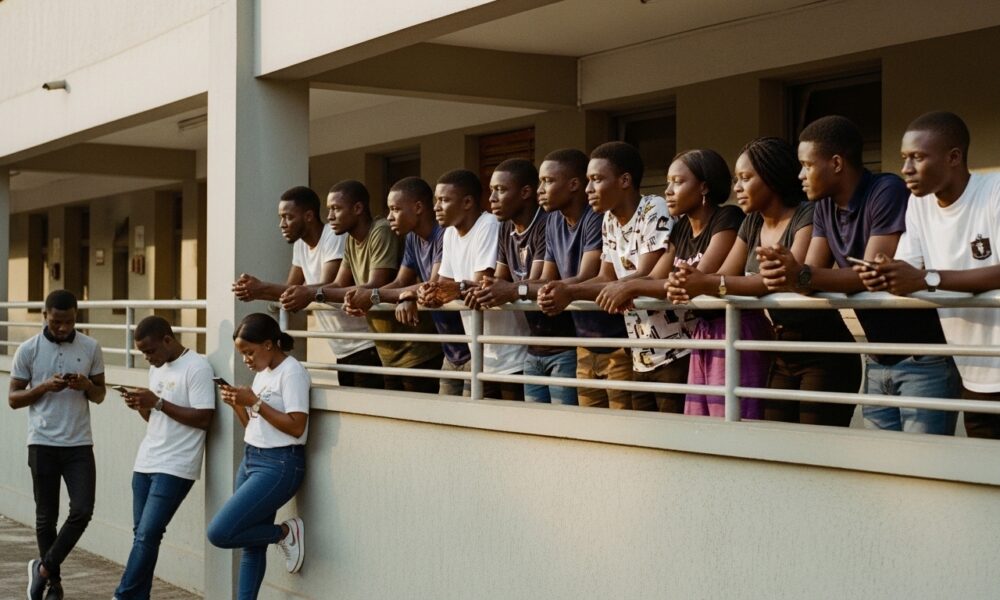

Eme Agbor, Tech Cabal, wrote that she met Garba at the University of Ibadan SME Fair in November 2025, moments after he concluded yet another pitch to a crowd of students, investors, and industry observers. Presenting Ecobag has become second nature to him.

The fairground buzzed with the kind of energy only student entrepreneurs seem able to create, with makeshift stands, improvised banners, hastily printed flyers, and prototypes laid out on plastic tables. While some teams pitched software apps and fintech tools, Garba’s corner smelled faintly of paper and dye.

He stood with a stack of brownish green bags in front of him, answering questions from anyone willing to listen and repeating his story with the same calm intensity each time.

Ecobag’s origins are rooted in Garba’s frustration with the scale of waste around him and the rising cost of packaging materials. His motivation took sharper shape after attending Afrotalks, a platform focused on African innovation and identity. The event reinforced his conviction that African solutions must be built with clear intentionality.

“Africans in the diaspora are returning home trying to understand and build value here. I realised it was already happening,” he said.

Afrotalks, for him, was more than a conference, it was a mirror. He listened to founders building clean energy solutions in rural Kenya, designers rethinking textiles using local fabrics, and economists challenging imported development models. Sitting in the audience, he felt a quiet but insistent question forming in his mind, What problem around you are you willing to dedicate years of your life to solving? That question lingered long after the event lights dimmed.

A Medical Outreach that Changed Direction

Garba traces the beginning of his sustainability journey to 2022, during a medical outreach to Epe village in Osun State. The trip was eye opening.

It was meant to be a straightforward humanitarian visit, with screenings, basic treatments, and health education. He joined primarily because he wanted to volunteer and see a bit more of the country beyond campus. But as the bus left the main roads and moved deeper into the village landscape, the scenery shifted from familiar to unsettling.

“As we travelled deeper, we saw massive drilling machines and large pits,”

He said.

“Yet the village itself was impoverished, malnourished children, crumbling buildings, no infrastructure. Even the Baale lived in a deteriorating house.”

The contradiction stayed with him. It strengthened his belief that Nigeria extracts immense value from rural communities while leaving those communities underdeveloped.

He returned to school with more questions than answers. How could there be such visible evidence of resource extraction and, at the same time, such visible neglect.

Why did development seem to move in one direction, out of the village and into distant cities or foreign accounts. Those images of children playing near dusty pits and broken buildings quietly rewired his understanding of value, ownership, and justice.

From Grass Experiments To a Patent

The idea for Ecobag did not begin with a search for a business model. It began when Garba stumbled on a video showing how dried grass could be transformed into a sheet of green paper.

He attempted to replicate the process but discovered that the type of grass used significantly affected the outcome. He tested multiple grasses, adjusting binders, refining mixtures, and challenging long standing academic assumptions about which fibres were suitable for papermaking.

In his small hostel room and on crowded laboratory benches, he turned bowls, buckets, and old trays into experimental equipment. Some days, the mixture would come out too soggy, on others, it would dry into uneven, brittle sheets.

He logged each experiment in a notebook, noting dates, ratios, types of grass, and drying times, slowly building a personal database of failures and partial successes. Classmates sometimes teased him about his “grass obsession”, but a few offered to help him collect samples from lawns, fields, and roadside patches.

His lecturer advised him to use a conventional variety of grass, but Garba’s experiments proved that the alternative he preferred could achieve the results he wanted. The challenge, however, was not only technical. Sourcing sufficient volumes of cut grass would require building a network of gardeners and landscapers, a complex and inefficient system for a small company trying to scale.

He sketched crude supply chain diagrams, tried to map who cut grass where, and even approached some landscaping workers outside estates to ask what they did with their clippings. The answers were predictable, they burned them, dumped them, or left them to rot. Turning that loosely organised waste stream into a reliable industrial input quickly revealed itself as a logistical nightmare.

This bottleneck pushed him toward agricultural waste, which proved easier to collect consistently. After several iterations, he finalised a workable formula and eventually secured a patent for it.

The shift to agricultural residue unlocked new possibilities. Rice husks, corn stalks, and other crop remnants began to replace the unpredictable flows of lawn clippings. Farmers, initially skeptical, warmed up when they realised they could earn a little extra from material they would otherwise burn or discard. The patent, when it came through, was a quiet personal victory. It was proof that his tinkering had crossed into the realm of genuine innovation, something recognised and protected by law, not just admired by friends.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Building capacity with very limited resources

Scaling production posed a new obstacle. The manual process of converting grass into pulp and paper was too slow and too labour intensive. With little access to capital, Garba improvised.

“We built a low budget mini factory and bought machines that could improve the process compared to what I was doing by hand,” he said.

The “factory” is a modest space on the outskirts of town, more workshop than industrial plant. Second hand equipment sits beside handmade contraptions welded together by local artisans.

Buckets of pulp, drying racks, and stacks of experimental sheets compete for space with notebooks, tape measures, and improvised safety gear. During peak periods, music plays from a small speaker as they work, helping to make the long hours slightly more bearable.

The operation remains partly manual, but the growth required a stronger team.

Olawale Omofojoye, a close friend with a mechanical engineering background, joined to oversee raw material sourcing and technical improvements.

Christabel Egbegi, a childhood friend with a master’s degree in Environmental and Land Contamination, came in from the UK to support advisory and investment discussions.

Bringing them in changed the company’s rhythm. Omofojoye began sketching machine upgrades on scrap paper and thinking through how to increase output without drastically increasing costs. Christabel pushed the team to tighten their documentation, develop a clearer sustainability narrative, and prepare properly for conversations with investors who would eventually ask difficult questions about margins, regulations, and impact.

Garba admits forming the team was one of his most difficult transitions as a founder. “I knew I couldn’t continue handling production, pitching, and development alone. I needed people who understood what I was trying to build.”

Letting go of control was not easy. He had to learn to trust others with core parts of the work, accept feedback on ideas he was emotionally attached to, and define roles clearly instead of simply asking friends to “help”. Team meetings, sometimes held late at night over video calls or in noisy cafeterias, became spaces where they argued, refined strategies, and reminded one another of the bigger vision.

Testing the Product in Real Conditions

During my visit, I tested an Ecobag prototype. The texture was coarse, an effect of the current processing machine, and the bag had slim, paper based handles. On a market run, it carried groceries without tearing. Over the next few days, I used it alternately as a lunch bag, a shopping bag, and an extra carry on. After nearly a week, the handles began to loosen slightly due to perspiration from my hands.

He said to Eme Agbor.

Using the bag in real life brought the trade offs into sharp relief. It lacked the glossy finish and smoothness many city shoppers have come to associate with imported kraft paper, yet it felt sturdier than it looked. Market sellers examined it with curiosity, squeezing the sides, tapping the base, and asking how much it would cost compared to the nylon bags they were used to. A few asked if their shop logos could be printed on it, others simply nodded and said that at least this one would not choke the gutter.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Garba explained that the rough surface is a temporary limitation of their machinery.

“We’ll achieve smoother textures once we acquire better equipment,” he noted.

The handles, he emphasised, are intentionally made from paper because the goal is complete biodegradability.

He talked about the tension between aesthetics and ethics, and how easy it would be to add a bit of plastic reinforcement to the handles or coat the surface to make it shinier. Those tweaks would make the bags more attractive to some buyers, but they would also undermine the very principle of the project, which is creating packaging that can return safely to the environment after use.

Visibility, Demand, and Alternative Funding Routes

One short Instagram video significantly boosted Ecobag’s visibility. The clip, originally created for a competition, attracted enquiries from individuals and businesses looking for cheaper, eco friendly packaging.

The video was simple, a quick montage of agricultural waste being shredded, pulped, pressed, and finally emerging as a functional bag. Garba’s voiceover explained the basic process in under a minute.

Within days, the comments section filled with questions, such as “Can this carry hot food”, “How much per pack”, and “Do you ship outside Ibadan”, along with encouragement from people delighted to see a tangible sustainability product built locally.

At the Global Exhibition event this year, several food and cosmetic companies expressed interest, confirmation that there is demand for a cost effective alternative to imported kraft paper bags.

Those conversations were early stage and exploratory, but they hinted at a future in which Ecobag might supply packaging not just to small vendors but to established brands seeking to reduce their environmental footprint. Some of the companies wanted custom sizes, others asked about printing, moisture resistance, and how quickly Ecobag could scale if they signed a contract.

Competitions and events have also strengthened Ecobag’s profile. In March 2025, Garba won Innotech 3.0 as the overall champion. At the Cleva App Business Challenge (YC 2024) in July 2025, he earned the Most Innovative Award and a 250 dollar prize. These platforms have helped the company build credibility in the sustainability and manufacturing space.

The cash prizes were modest compared to the capital required for industrial machines, but they were symbolic boosts. They paid for new blades, replacement parts, transportation to yet another demo, and, just as importantly, they helped the team believe that Ecobag was not just a school project. Judges’ feedback from these competitions often pushed them to refine their business model, think through unit economics, and articulate how their impact could be measured beyond feel good language.

Behind The scenes: The Difficult Part No Audience Sees

Despite the public recognition, Garba keeps returning to the long, difficult work required to build a real company. In mid 2025, he registered for an 8 week programme sponsored by the British Council and King Trust International in Abeokuta. The timing clashed with his exams, and attending required commuting between Ibadan and Abeokuta multiple times a week.

His co founder, Omofojoye, contributed funds to make the trips possible. With no accommodation, Garba often slept on the floor under a staircase in a building just to arrive early for classes.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

The programme sessions covered topics like financial modelling, market validation, legal structures, and leadership. Surrounded by other founders who were also juggling day jobs, schoolwork, or family responsibilities, he realised that sacrifice was a constant theme in entrepreneurship.

On particularly exhausting days, hunched over his notes on the staircase floor, he wondered if it would be easier to pause Ecobag until after graduation. Each time, conversations with his team and the memory of Epe village drew him back.

What Comes Next

Ecobag Mart is now focused on moving from prototype phase production to a scalable system, refining the paper’s appearance, improving its texture, and increasing output. For Garba, the goal is straightforward, prove that local ingenuity can tackle global challenges such as waste, pollution, and sustainable packaging.

The roadmap involves more than just buying better machines. It includes building a tighter network of agricultural suppliers, investing in quality control, and partnering with designers who can help make the bags visually appealing without compromising their biodegradability.

There is also a growing interest in exploring other product lines, such as tissue, packaging inserts, or simple stationery, using the same agricultural waste stream.

From missing an engineering admission to building a patented eco innovation, Garba’s story reflects a growing movement of African students creating solutions grounded in necessity, resilience, and resourcefulness. Across campuses and communities, young innovators like him are asking hard questions about how things are made, who benefits, and what happens when products reach the end of their life cycle.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...