African Tattoos and Scarification: Ancient Ink, Living Identity

Tattoos are more than just ink on skin. Around the world, they serve as badges of identity, belonging, memory, and transformation. But when it comes to African tattoos and scarification, the meanings run even deeper. These body markings are cultural blueprints, spiritual codes and social scripts passed down through bloodlines and ceremonies. They tell stories of survival, love, bravery, status, and heritage. And unlike the modern trend-driven ink of the West, African tattoos are often sacred, a living archive etched into the skin.

In this feature, we’ll journey across Africa to explore some of the continent’s most fascinating tattoo and scarification traditions. From the sands of the Sahara to the rainforests of Central Africa, these practices reflect Africa’s vast ethnic diversity and ancestral wisdom.

Tifinagh Tattoos: Ancient Letters of the Tuareg

In the Sahara Desert, the Tuareg people, a Berber ethnic group, are famed for their use of Tifinagh script, one of the oldest alphabets still in use today. For over 2,000 years, this script has been a mark of identity and mysticism.

Tuareg women traditionally receive facial and hand tattoos during initiation ceremonies. These tattoos often include Tifinagh characters and are believed to offer protection during desert journeys, symbolize purity, and confirm a young woman’s transition into adulthood.

An image showing Tifinagh characters

These tattoos are not random decorations; they are spiritual and linguistic emblems — a way of wearing one’s language, heritage, and power. According to scholars, these designs were also used to ward off evil spirits and preserve health during childbirth.

Adinkra Tattoos: Symbols of Soul Wisdom

Originating among the Akan people of Ghana and Ivory Coast, Adinkra symbols were once reserved for royalty, printed on cloth worn during funerals and spiritual gatherings. Each symbol holds a philosophical meaning, from courage and perseverance to community and divine order.

Over time, Adinkra symbols moved from fabric to skin. Today, many Ghanaians and diaspora Africans tattoo Adinkra icons as personal mantras or moral guides.

For instance:

The Eban, also called Iban, simplifies security, love, and safety; the Dwennimmen represents humility and strength, while the Fawohodie signifies freedom and emancipation. These tattoos are visual proverbs — poetic, profound, and deeply personal.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Fulani Facial Tattoos: Grace in Geometry

Among the nomadic Fulani people, who span countries like Nigeria, Senegal, and Mali, facial tattoos are small yet significant. Often made up of dots and lines arranged around the cheeks, eyes, and forehead, these tattoos convey messages about marital eligibility, fertility and tribal affiliation

Fulani facial tattoos are typically given to girls as they reach puberty, often passed down from mothers and grandmothers. The application is both painful and celebratory, and the outcome is seen as a symbol of beauty and strength.

Today, some Fulani women still proudly wear these marks, while others reimagine them in modern tattoo art.

Nuba Scarification: Wounds That Speak

An image showing what the Nuba tattoo would look like

The Nuba people of Sudan practice one of the most intricate forms of scarification. Using razors or sharp stones, geometric patterns are cut into the skin, often on the chest, shoulders, or back. These scars are not random, as each design tells a life story.

Common meanings behind the marks include: coming of age, readiness for battle, achievements, or status within the tribe

The raised skin, formed through careful healing techniques, becomes a kind of body armor, both symbolic and aesthetic. Scarification is often accompanied by dance and chanting, turning pain into a communal rite of resilience.

Maasai Warrior Marks: Blood and Bravery

For the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania, scars are symbols of bravery. At the heart of their warrior culture is Emuratare — a male initiation ceremony that includes circumcision and sometimes scarification.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Geometric scars on the face or arms mark a boy’s journey to warriorhood. These marks are done without anesthesia and under strict silence, teaching stoicism and emotional control.

During Maasai festivals, these scars are often accentuated with red ochre body paint, beads, and feathers, celebrating both cultural pride and masculine identity.

Berber Tattoos: North African Mysticism

The Berber (Amazigh) people of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia have used tattoos for millennia. Traditionally applied using charcoal and sharp needles, Berber tattoos carry multiple meanings, which include Spiritual protection includes marital eligibility, fertility, or tribal alignment.

Women typically receive tattoos on their chins, foreheads, and hands. Patterns include stars, crosses, and zigzags, which are symbols linked to Islamic, pre-Islamic, and indigenous beliefs.

Modern Berber women are reviving these tattoos, fusing ancient designs with new body art aesthetics as a way to reclaim Amazigh identity and resist cultural erasure.

Igbo Ichi Scarification: Signs of Nobility

Among the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria, Ichi scarification is historically reserved for the elite. Men belonging to title societies (such as the Nze na Ozo) receive symmetrical facial markings carved into the cheeks and forehead.

These marks symbolize: spiritual authority, social leadership and ancestral continuity

While largely discontinued in contemporary Igbo life, Ichi remains a revered part of the cultural memory, a reminder of pre-colonial systems of governance and respect.

Dogon Scarification: Maps of the Cosmos

The Dogon people of Mali are known for their rich cosmology and deep philosophical traditions. Scarification plays a role in spiritual rites, often mimicking celestial bodies or mythological motifs.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Marks on the torso, arms, or face are linked to ancestral spirits, clan lineage, and personal rites of passage

For the Dogon, these marks are more than cultural — they’re spiritual contracts, connecting the body to the cosmos and the ancestors.

San People’s Healing Tattoos

The San people (also known as Bushmen) of southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest surviving cultures. Their tattoos and scarifications are minimalist, often linked to healing dances or trance rituals.

Small incisions filled with ash or pigments are believed to release spiritual energy, treat illness, and open pathways to ancestors.

These marks are personal and functional — part of a larger belief system that sees the body as a spiritual vessel.

Kwele Body Marks: Sacred Mask Rituals

The Kwele people of Central Africa are best known for their striking wooden masks, but their body markings are equally symbolic. Tattoos are applied during initiation rituals and often echo the shapes of their ceremonial masks.

These marks represent ancestral protection, moral transformation, and community acceptance

Kwele tattoos are living extensions of their spiritual art, linking the body with the sacred symbols of the forest and spirit world.

Edo Scarification: Royal Bloodlines

The Bini (Edo) people of southwest Nigeria are globally recognized for their rich dynastic history and exquisite bronze artistry. Lesser known, but equally significant, is their cultural tradition of Iwu, a form of body scarification that symbolizes pride, strength, beauty, and the transition to adulthood.

Unlike many Nigerian tribes that emphasize facial tattoos, the Edo people traditionally place these marks on the stomach, sides, and torso.

Iwu is performed by a specialist known as the Osiwu (or Owisu, depending on dialect), the traditional body-sculpting surgeon of Edo society.

The standard markings consist of seven strokes for males and sixteen for females, while royal children, sons and daughters of the Oba (king), receive one fewer mark, symbolizing their distinct social status.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Beyond maturity rites, Iwu also served aesthetic and identity functions, distinguishing Edo indigenes from outsiders. As such, non-indigenes and enslaved individuals were not permitted to receive Iwu, reinforcing its role as a mark of cultural belonging.

Why These Tattoos Still Matter

African tattoos and scarifications like Iwu were never just about aesthetics — they were living symbols of identity, honour, and belonging. Each line told a story: of lineage, of bravery, of becoming. For the Edo people and many others, these marks were milestones — signifying adulthood, ancestry, social standing, and cultural pride.

Though the tools have changed and the meanings have evolved, the essence remains. These tattoos still matter because they represent more than skin; they are memories made visible. They are quiet declarations of who we are, where we come from, and the legacies we carry forward.

In every blade-stroke and ink line lies a truth: to mark the body was to mark a life. And in reclaiming these traditions today, we honour the past not by preserving it in glass, but by wearing it with purpose.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

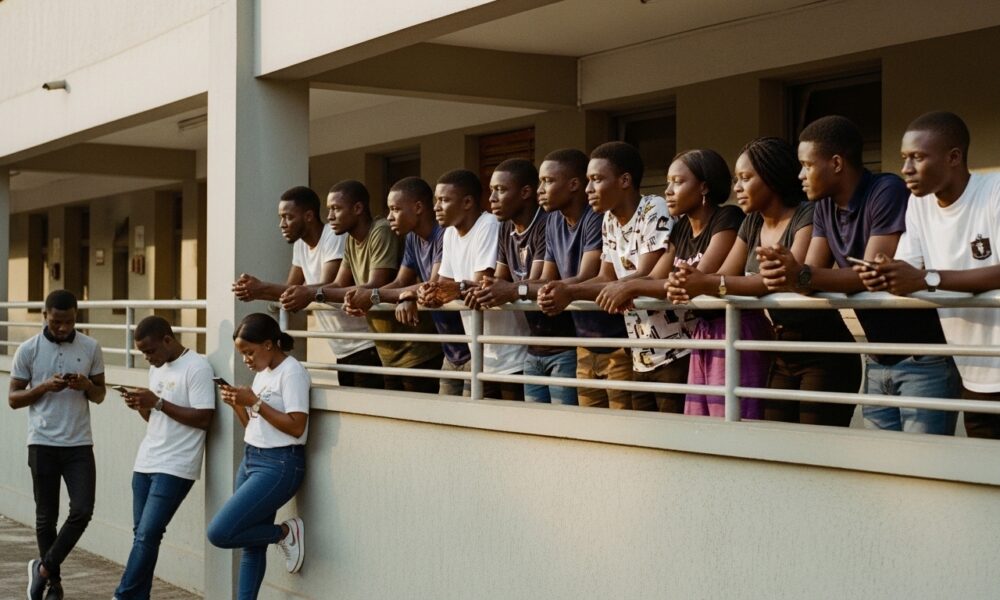

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...