The Rotten Mold That Saved Millions: How Alexander Fleming’s "Mess" Changed Medicine Forever

Sometimes, history is not written in the careful pages of a well-kept notebook or in the polished lab of a Nobel-winning genius. Sometimes, it is scribbled in the margins of a cluttered desk, growing quietly on a forgotten dish. That’s how the world’s first true antibiotic—penicillin—was discovered. And it all began with a curious man, a holiday, and a patch of mold.

Today, penicillin is credited with saving over 200 million lives. Yet the moment of discovery was so ordinary it could have gone unnoticed. Had Alexander Fleming been a little neater, a little faster to clean up, or a little less curious, the course of medicine might have taken a very different path.

Setting the Scene: A Time Before Antibiotics

To truly understand the significance of Fleming’s discovery, one has to imagine a world without antibiotics. Before the 20th century, infections were a death sentence. Soldiers wounded in battle often died from infected wounds rather than their injuries. Childbirth, surgeries, or even a simple scratch from a rose bush could lead to sepsis—a systemic infection with no cure.

Diseases like pneumonia, syphilis, gonorrhea, scarlet fever, and strep throat claimed countless lives. Doctors were virtually helpless against them. Treatments ranged from herbal remedies to arsenic-based compounds, often doing more harm than good.

The medical world was desperate for a substance that could kill bacteria without harming the human body. But no such “magic bullet” had been found.

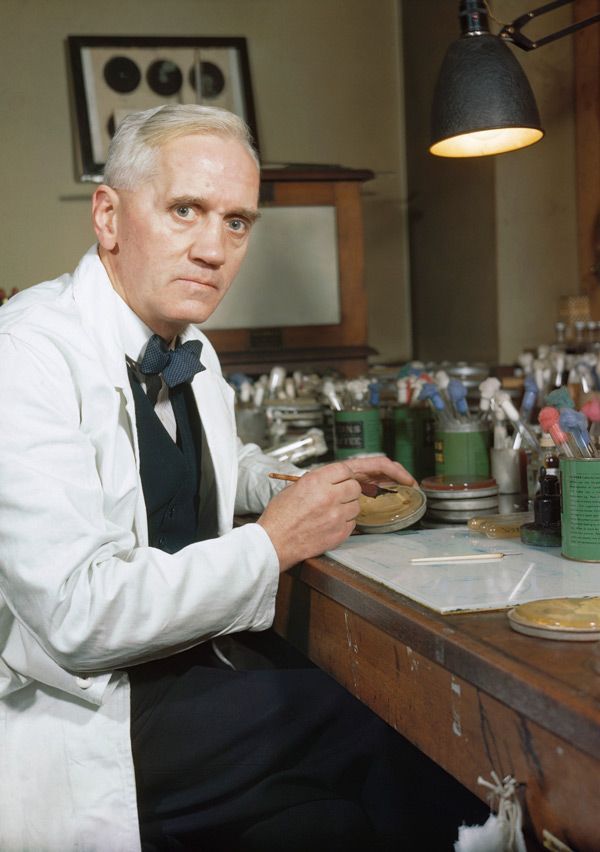

The Curious Scotsman: Who Was Alexander Fleming?

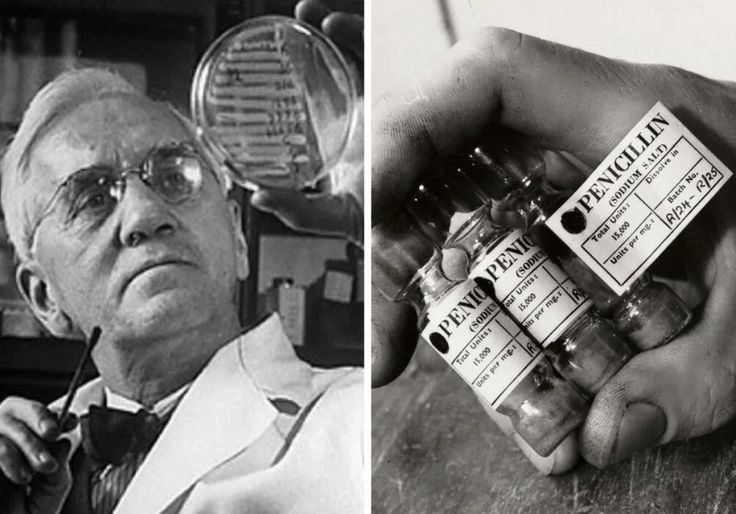

Born in 1881 in rural Scotland, Alexander Fleming was a quiet, observant child raised on a farm. He went on to study medicine in London, eventually specializing in bacteriology. By the 1920s, Fleming was working at St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School, part of the University of London.

Though known for his sharp mind, Fleming was also famously disorganized. His lab bench was often cluttered with petri dishes, cultures, and test tubes, many left unwashed or unlabeled for days. Some colleagues joked that he never cleaned anything until mold forced him to.

But that messiness, paired with an unusually inquisitive mind, would one day change history.

The Accident: Mold, Vacation, and a Forgotten Dish

In the summer of 1928, Fleming left London for a two-week vacation. Before leaving, he had been working on experiments involving staphylococcus bacteria, trying to understand ways to combat infection. Dozens of petri dishes were left on his lab bench, some of them exposed to the open air.

Upon returning on September 3, 1928, Fleming began sorting through his dishes. Most were as expected—bacteria had grown in predictable patterns. But one dish was different.

A spot of bluish-green mold had formed. Around this mold, a strange thing had occurred: the bacteria had been completely dissolved, creating a clear, ring-shaped halo.

This dish could easily have been tossed out as contamination. But Fleming, instead of discarding it, paused.

“That’s funny,” he reportedly muttered.

And with that moment of curiosity, the future of medicine tilted.

Penicillium Notatum: The Mold That Changed the World

Fleming identified the invader as Penicillium notatum, a strain of mold. He carefully cultured it and began experimenting. What he discovered was remarkable:

The mold secreted a substance that killed a broad range of harmful bacteria.

It was non-toxic to animal tissue.

It worked even in diluted form.

It did not kill all microbes, only specific bacteria—particularly Gram-positive ones like streptococcus and staphylococcus.

Fleming named the substance penicillin, after the Penicillium mold.

He realized the potential immediately. In his 1929 paper published in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, he wrote that penicillin was “a powerful antibacterial agent.” However, he couldn’t isolate or stabilize it in a form suitable for human treatment.

To the scientific world at large, Fleming’s paper was largely overlooked. The impact of his discovery would take more than a decade to be fully realized.

The Missing Link: Enter Florey, Chain, and Heatley

The breakthrough came in 1940, thanks to a group of researchers at the University of Oxford. Howard Florey, Ernst Boris Chain, and Norman Heatley revisited Fleming’s 1929 paper. Intrigued, the team began investigating penicillin. They faced enormous challenges: the mold was fragile, grew slowly, and the yield of penicillin was tiny. But through trial and error, they developed techniques to extract, purify, and concentrate the antibiotic.

By 1941, they had tested penicillin on mice and one human patient. The patient’s improvement was dramatic, but he died when the team ran out of penicillin. The message was clear: the drug worked. They just needed more of it.

War, Industry, and the Penicillin Boom

World War II provided the urgency—and funding—that penicillin needed to become a reality. The Allies saw it as a strategic asset: a way to save soldiers, reduce amputations, and win the war against infection.

The U.S. government partnered with pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer to find a way to mass-produce penicillin. Scientists eventually discovered that a strain of Penicillium found on a moldy cantaloupe in a Peoria, Illinois market produced far more penicillin than Fleming’s original.

By 1944, penicillin was available in abundance. The Normandy invasion (D-Day) was the first military campaign in which thousands of wounded soldiers were treated with antibiotics. Deaths from battlefield infections plummeted.

Fleming’s Nobel Prize and Final Warning

In 1945, Alexander Fleming, Howard Florey, and Ernst Chain shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Fleming was now hailed as a hero. Yet he used his newfound fame not to gloat, but to warn.

“The greatest possibility of evil in self-medication is the use of too-small doses… exposing bacteria to non-lethal quantities may make them resistant.”

His words were prophetic. Today, antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health, fueled by the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture.

Impact on Medicine and Humanity

The discovery of penicillin didn’t just save lives—it transformed medicine:

Infections that once killed became treatable.

Complex surgeries became safer.

Childbirth-related deaths plummeted.

Organ transplants and chemotherapy became possible due to the ability to prevent post-op infections.

By conservative estimates, over 200 million lives have been saved since penicillin’s discovery.

Entire families, generations, and communities exist today because one man didn’t throw away a contaminated petri dish.

The Mystery and Irony of Discovery

Fleming’s story is as much about humility and curiosity as it is about science. He did not invent penicillin. He discovered it. Nature had always made it—Fleming just happened to notice.

His discovery is a case study in serendipity—but also in the importance of recognizing potential, following the evidence, and sharing findings even when no one’s paying attention.

The irony? Fleming’s disorganization—long considered a flaw—played a pivotal role. Had he been more diligent, he might have cleaned that dish before the mold had time to grow.

Penicillin Today: Still a Pillar, but Under Threat

Penicillin remains a cornerstone of modern antibiotics. Variants like amoxicillin, ampicillin, and methicillin are widely used. However, the rise of multi-drug-resistant bacteria—or “superbugs”—now threatens the effectiveness of antibiotics.

According to the World Health Organization, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) could lead to 10 million deaths per year by 2050 if not addressed.

We are, in some ways, returning to a world where basic infections could once again become untreatable. The need for new antibiotics, better stewardship, and global cooperation has never been more urgent.

Conclusion: The Power of Noticing the Unnoticed

In a time when the world looks to technology, billion-dollar labs, and AI to solve its biggest problems, the story of penicillin reminds us of something powerful:

Sometimes, world-changing ideas don’t start with a breakthrough. They start with a mess. A mistake. A curious glance. A single question:

“What’s this mold doing here?”

In Fleming’s moldy dish was not just bacteria-eating fungus. It was the beginning of modern medicine. A quiet revolution that continues to echo through every hospital, clinic, and pharmacy today.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...