Is It Wrong to Expect Our Leaders to Be Angels?

We don’t vote for angels; we vote for human beings. And yet every election season, across Africa and beyond, we audition leaders for sainthood. We assess not just their policies but their purity: Will they resist corruption? Will they be humble, tireless, and incorruptible? If they are not, we feel betrayed, as if we were promised a halo and got only a haircut.

When we elect leaders in Africa, or anywhere in the world, we don’t just hand over power; we hand over hope. We expect them to be visionaries, saints, and problem-solvers all rolled into one. We want competence, but we also want character. We want them to deliver roads, schools, and hospitals, but we also demand they do it with pure hands, untainted by greed or scandal.

But here’s the unsettling truth: expecting angelic leaders often makes our politics worse. It sets up emotional cycles of messiah worship and total disillusionment, while distracting us from the dull, necessary work of building institutions that protect the public from anyone’s flaws.

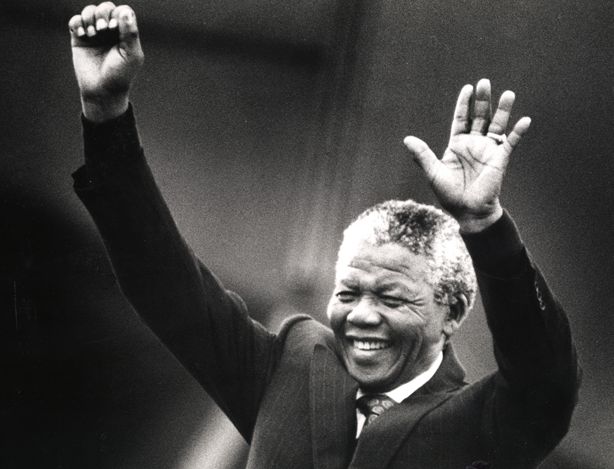

The question isn’t whether it’s wrong to long for angels; hope is human. The real mistake is designing our politics as though angels are coming. Even icons push back against sanctification.

Photo Credit: Pinterest | Nelson Mandela famously said he was “not a saint, unless you think of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying.”

Why we keep reaching for halos

There are understandable reasons. Many African countries have suffered leadership failures so deep that citizens naturally equate change with moral rebirth. When you’ve lived through state capture, manipulated procurement, or public funds vanishing into private hands, the instinct is to demand not just a competent manager, but a moral saviour.

Data shows that public trust in political institutions has eroded across the continent, with citizens trusting religious leaders, the army, and traditional leaders more than elected officials. That trust decline fuels a longing for singularly “good” leaders who can cleanse the system through personal virtue.

But if politics is designed around extraordinary virtue, it fails under ordinary frailty. And humans—even good ones—are frail.

The danger of angel-worship

First, it breeds cynicism. When angels fall (and they always do), people don’t just lose faith in a politician; they lose faith in democracy itself. Afrobarometer has tracked a worrying slide in trust toward political leaders and institutions, a trend that correlates with fatigue and apathy, especially among youth.

Second, it scares away talent. Who wants to enter public service if the job description reads: “Perfect or perish”? High-integrity professionals may avoid politics altogether because one misstep, an unguarded quote, a botched procurement reform, an overzealous ally, can trigger moral panic.

Third, it neglects system design. Saints don’t need guardrails; humans do. The assumption that personal goodness can substitute for public architecture is precisely how nations drift into fragile governance.

Photo Credit: AI generated |The myth of the flawless leader; we keep searching for halos in politics

Proof from history: when virtue isn’t enough, and when systems work

South Africa’s hard lessons on personality vs. institutions.

The post-apartheid promise collided with a grim reality during the “state capture” era. The Zondo Commission later documented, in extraordinary detail, how networks of political and private sectors entrenched corruption and hollowed out state capacity, showing how institutional vulnerabilities, not just individual vices, enable systemic rot. The commission’s six-part reporting provides a blueprint for accountability, precisely because it is institutional rather than personal.

Earlier, South Africa learned another searing lesson about the cost of moral misjudgment at the top: HIV/AIDS denialism in the early 2000s. A Harvard-led analysis estimated more than 330,000 preventable deathsdue to delays in providing antiretroviral therapy and prevention of mother-to-child transmission during that period, evidence that a leader’s ideological blind spot, unchecked by institutional resistance, can be catastrophic.

Kenya’s Supreme Court: institutions over halos.

In 2017, Kenya offered a different kind of headline. Its Supreme Court annulled a presidential election, ordering a fresh poll and signaling that rules, not personalities, would decide the highest stakes. You don’t need an angel in the State House if you have a court brave enough, and independent enough, to enforce the Constitution.

It was the first time a court in Africa invalidated a presidential result, and it changed what citizens elsewhere could imagine about the power of institutions.

Tanzania’s pandemic pivot: when policy changes, outcomes change.

During the COVID-19 crisis, Tanzania initially embraced public denial, halting data releases and shunning mainstream prevention measures. After a leadership transition in 2021, policy shifted: scientific advisory capacity was restored and engagement with global health guidance resumed. The point isn’t to canonize or demonize individuals; it’s to observe that systems that allow course correction, expert committees, transparent data, and independent media can tame the damage of bad calls and accelerate better ones.

The numbers don’t lie: corruption remains systemic

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2024 again ranks Sub-Saharan Africa as the lowest-scoring region globally, with an average of 33 out of 100 and 90% of countries below 50 out of 100, a sobering reminder that the problem is structural. This isn’t a handful of fallen angels; this is a landscape of weak safeguards.

If corruption is systemic, then moral charisma is not a strategy. Architecture is. Budgets that are published and trackable. Procurement that is open by default. Whistleblowers who are protected, not punished. Courts and audit offices that can bite, not just bark.

Photo Credit: AI |Without strong institutions, even “angelic” leaders can be crushed by corruption.

What “strong institutions” actually look like (with African examples)

1) The right to know, backed by law.

Countries that operationalize transparency, not just preach it, change the incentives. Ghana’s Right to Information Act (2019) operationalizes a constitutional right and created a commission to oversee implementation, slow, imperfect, but a legal shift from secrecy to disclosure. Nigeria’s Freedom of Information Act (2011) similarly makes public records accessible, empowering journalists and citizens to interrogate spending and policy. These are not silver bullets, but they move power from personalities to procedures.

2) Courts with a spine.

Kenya’s 2017 precedent didn’t make Kenya angel-proof, but it raised the cost of impunity. Political actors now calculate with the court in mind. That is what institutions do: they change behaviour before a crisis, not just punish after it.

3) Commissions that investigate and publish, not bury.

The Zondo process was painful and politically messy. Yet by naming names, describing networks, and recommending reforms, it turned suspicion into a public record—a foundation for prosecutions, corporate reform, and administrative changes, even if implementation remains contested.

4) Open money, from procurement to performance.

Transparency International’s findings underline that anti-corruption efforts succeed where budgets are open, procurement is competitive, and civil society can monitor. Publishing line-item budgets, e-procurement portals, beneficial ownership registers—these are the unglamorous tools that protect a nation from anyone’s worst day.

The youth factor: expectations vs. engineering

Africa is the youngest region on earth, about 70% of sub-Saharan Africans are under 30, and they carry both the hope and the heartbreak of public life. Young citizens are rightly demanding leaders who are honest and effective. But youth activism achieves more, faster, when it channels moral energy into institutional engineering: FOI requests; budget monitoring clubs on campuses; citizen dashboards that track campaign promises and service delivery; civic tech that scrapes procurement data for red flags; strategic litigation to expand access to information and protect journalists.

Put differently: youth movements win when they design systems that force leaders to behave better, rather than waiting for leaders who were born better.

Photo Credit: AI | Stronger institutions, not angelic leaders, are what safeguard democracy.

A more realistic standard for leadership

If not angels, what should we ask for?

Humility over halo. We need leaders who can say “I was wrong,” and correct course. That requires an ego small enough to listen and a team fearless enough to disagree.

Competence with constraints. Great leaders invite constraints—inspections, audits, and public scorecards—because they know performance improves under scrutiny.

Coalition-builders, not cult leaders. Leaders who spread decision-making across institutions leave fewer choke points for corruption or collapse.

A bias for transparency. Publish the budget. Livestream the tenders. Report the metrics monthly. Routine sunlight beats sporadic revelations.

What citizens can do this year

You can’t summon angels. You can strengthen guardrails:

Use the laws you have. File an RTI request in Ghana or an FOI request in Nigeria to obtain contract details, project milestones, or budget performance reports for your local hospital or road. The more citizens use these tools, the harder it becomes for officials to ignore them.

Watch the money, not the speeches. Follow the procurement notices, auditor-general reports, and performance dashboards. Post simple explainers on social media: “₦2.5bn for boreholes—how many drilled? Where?” Accountability thrives on specificity.

Back the referees. Defend the independence of courts, auditors, electoral commissions, and anticorruption bodies—regardless of which party benefits today. Tomorrow it could be yours.

Normalize course corrections. Reward leaders who reverse bad decisions. We can’t say “we want leaders who learn” and then punish every U-turn as weakness.

Invest in civic data. Support organizations and startups that clean, visualize, and publish public data (spending, procurement, school results, clinic stock-outs). Information is oxygen for accountability.

Reframing the national conversation

Imagine a political culture where the headline question isn’t “Is she a saint?” but “What happens if she isn’t?” If the budget is online, tenders are open, and courts are unafraid, then even a flawed leader can’t do lasting harm. Conversely, even an angel becomes a liability in a system that runs on secrecy, arbitrary discretion, and personal loyalty.

That reframing doesn’t cheapen our ideals; it protects them. It shifts our energy from curating personalities to constructing guardrails. It accepts that leaders are temporary and human, while institutions can be durable and impartial.

The uncomfortable paradox

Angel expectations can be a form of escapism. They let us outsource our civic responsibilities to a single figure. But democracy is not a spectator sport. It is a habit: reading budgets, filing requests, voting in local races, supporting civil society, defending independent media, insisting on the boring procedures that make theft hard and honesty easy.

If we keep praying for angels, we will keep getting humans—and keep being disappointed. If we build for humans, we may finally get the outcomes we always associated with angels: clean government, fair rules, predictable justice.

Closing argument

So, is it wrong to expect our leaders to be angels? It isn’t wrong to wish it. Hope is a feature, not a bug, of citizenship. But it is dangerous to design our politics around that wish. The safest country isn’t the one that elects a saint; it’s the one that can survive a sinner.

Build systems that assume human error, human weakness, human ambition—and channel them toward public good. Then, if an angel does show up, wonderful: they’ll thrive inside institutions that make goodness effective. And if they don’t (and they usually won’t), the nation will still be fine.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...