When the Moon Was a Calendar: Africa’s Forgotten Timekeepers

Before the clock, there was the sky. Before the calendar, there was the moon; soft, cyclical, and unrelenting in its rhythm. Across Africa, long before the Gregorian system arrived, time was measured not in dates but in stories, songs, and shadows. To many communities, the night sky was not a mystery but a mirror, reflecting their connection to the divine, the seasons, and one another.

The First Calendar Was Written in the Sky

Thousands of years ago, in what is now Uganda, the Bachwezi people observed lunar phases to plan harvests, rituals, and migrations. Similar practices existed across the continent: in West Africa, the Yoruba calendar relied on a 28-day lunar cycle tied to market days and spiritual observances, while the Dogon people of Mali built entire cosmologies around the movement of Sirius, the brightest star visible from Earth. To them, the universe was an intricate dance, and time was its rhythm.

In these societies, keeping time wasn’t about precision but it was about balance. The moon’s glow marked moments of fertility, rest, and renewal. Communities sang under its light, married beneath its crescents, and prayed during its eclipses. The concept of time was sacred, circular, and deeply human.

Counting Time Before Numbers

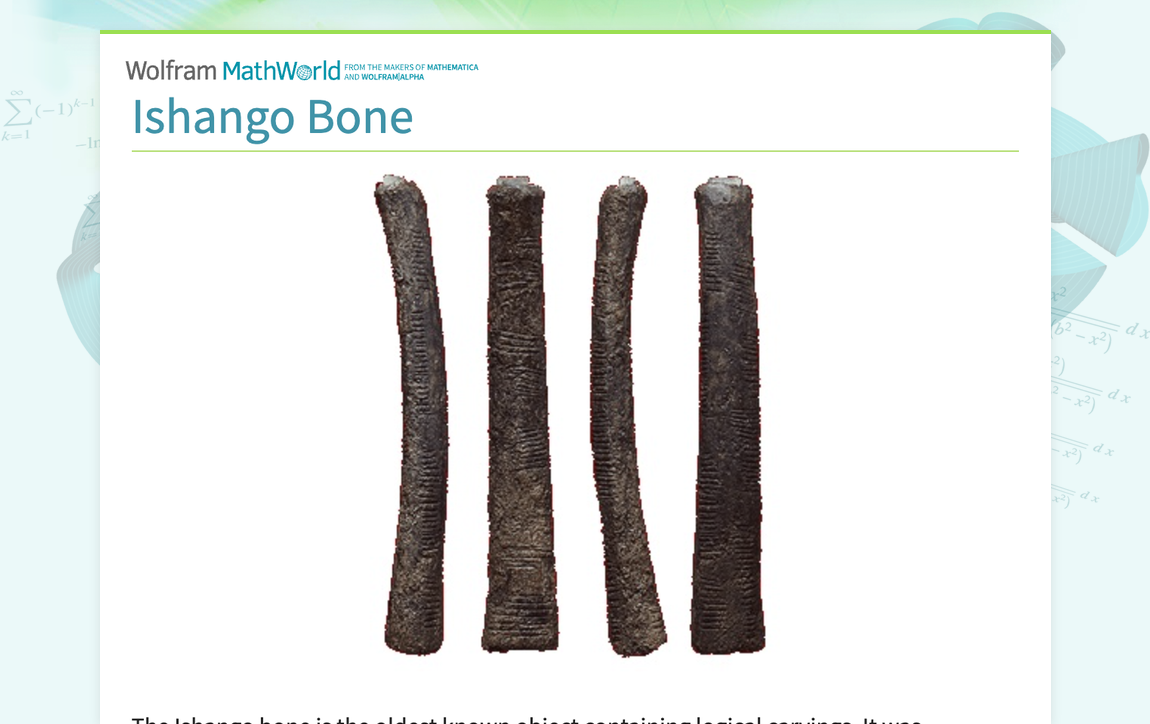

Archaeologists have traced one of the oldest known lunar calendars to Ishango, near the headwaters of the Nile in modern-day Congo. There, a 20,000-year-old bone, the Ishango Bone which is etched with notches believed to correspond to moon cycles. Long before Egypt’s pyramids or Rome’s empire, African peoples were already recording the passage of time with purpose and precision.

In ancient Egypt, timekeeping became monumental. The Egyptians aligned their calendar with the annual flooding of the Nile, guided by the heliacal rising of Sirius. This early solar-lunar system would later inspire Greek and Roman chronologies, though its African roots are often overlooked. It was Africa’s skywatchers, it was not Europe’s scholars, who first treated time as both a science and a spirit.

The Moon, the Market, and the Month

In Yoruba towns, market women once followed a four-day calendar which were ‘‘Ojo Awo, Ojo Ogun, Ojo Jakuta, and Ojo Obatala’’ and each of them linked to a deity and economic rhythm. It was a living calendar that synced with the moon’s phases. Traders knew which days were lucky, farmers knew when to plant, and priests knew when to sacrifice. The system was local yet universal and they are what anthropologists now call indigenous timekeeping, rooted in nature and necessity.

Even the Swahili calendar used along the East African coast mixed Arabic lunar reckoning with Bantu sensibilities. Months were named for rains, harvests, or winds. Time was practical, it was a dialogue between human life and environmental rhythm.

This relationship between time and environment wasn’t merely cultural; it was ecological. When the moon waned, fishers rested. When it waxed, they sailed. The stars dictated when to sow millet or when herders could move their cattle. It was astronomy woven into survival.

Time as Story, Not Schedule

Colonialism disrupted these rhythms. European missionaries and administrators brought the Gregorian calendar, dismissing local systems as “primitive.” Time, once cyclical and sacred, became linear and mechanical. Church bells replaced drum signals; wristwatches replaced moonlight. Yet fragments of older systems survived in rituals, in language, in memory.

Among the Igbo of Nigeria, for instance, the traditional Izu (week) still divides time into four market days. The Akan people of Ghana name children after the day of the week they were born, Kojo for Monday, Afua for Friday and this was preserving a sense of identity tied to cosmic rhythm. Even today, African time is often mocked as “elastic,” but beneath that joke lies an ancient philosophy: that time should serve life, not the other way around.

When Astronomy Was Spiritual

The Dogon’s cosmology, documented by anthropologists like Marcel Griaule in the 20th century, describes celestial knowledge that predates Western astronomy. They knew of Sirius B, a companion star invisible to the naked eye, long before telescopes could confirm it. While this claim remains debated, it underscores a truth that African cosmology treated science and spirituality as one.

In Northern Africa, the Berbers of the Sahara also kept lunar-solar calendars tied to agricultural cycles. Nomadic tribes read stars as guides across endless deserts. Time, to them, was not an abstraction but it was navigation. Every constellation was a compass, every moon a map.

The Science Beneath the Myth

Modern researchers are rediscovering the sophistication of these systems. Scholars at the University of the Witwatersrand have studied ancient rock engravings in South Africa’s Blombos Cave, linking them to early astronomical observation. The carvings are estimated to be over 70,000 years old, suggesting that Africans were charting celestial patterns tens of millennia before written history.

Similarly, in Ethiopia, the Ge’ez calendar which is still in use today runs seven years behind the Gregorian system and includes 13 months. It remains one of the world’s oldest continuous time systems, proving that Africa’s temporal logic was neither broken nor backward, merely different and deeply embedded in worldview.

The Return of Cosmic Wisdom

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Today, as technology reshapes how we measure and manage time, there’s a quiet resurgence of interest in indigenous knowledge systems. African astronomers, like those at the South African Astronomical Observatory, are reinterpreting traditional sky lore alongside modern data. Apps are emerging that document local star names and moon traditions, bridging ancient wisdom and digital innovation.

In a world where everyone is racing against the clock, Africa’s ancient timekeepers offer a radical alternative; a slower, cyclical, and communal rhythm of life. They remind us that time can be something to live within, not to chase.

A Rhythm Worth Remembering

As cities sprawl and neon lights outshine the stars, it becomes easier to forget that time once lived in the sky. Yet somewhere in the quiet of a rural night, an elder still raises their head and notes the moon’s face knowing, as their ancestors did, what season is coming. The future may belong to atomic clocks and satellites, but the past still hums in every lunar glow. Africa once measured time by memory, moonlight, and meaning and perhaps, it still does.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...