The Rookie FDA Doctor Who Saved Hundreds of America’s Babies From Birth Defect Catastrophe

Imagine a pill that feels like it could have its own aesthetic. Advertised as gentle, modern, science approved. Your doctor smiles and says it is totally fine, especially if you are pregnant and tired and just want to sleep through the nausea.

Now imagine finding out that same pill is quietly causing thousands of babies to be born with severe birth defects in dozens of countries.

In the middle of that storm, before most people even knew anything was wrong, one brand new doctor at the FDA in the United States looked at the data, saw the holes, and did something brutally simple. She refused to sign the approval form.

The doctor who protected an entire generation of children did it with one quiet, stubborn word: no.

The “Safe” Pill That Was Everything But Safe

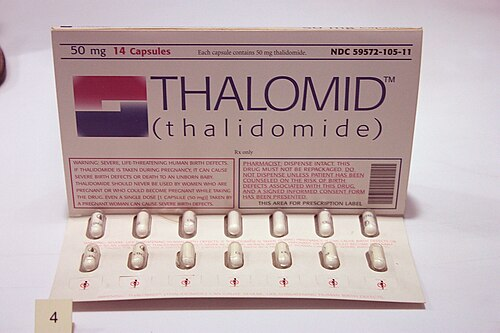

The drug was called thalidomide. It was first sold in West Germany in the late 1950s and quickly spread to 40 plus countries under names like Contergan and Distaval. It was pitched as a kind of miracle helper. Trouble sleeping, stressed, pregnant and constantly sick, thalidomide was marketed as the calm-in-a-capsule solution.

Back then, the rules around drug testing were way looser. A lot of people believed medicines could not cross the placenta, so if a pregnant woman took something, her baby was assumed to be safe by default. Animal tests focused on basic toxicity, not what happened to embryos. Nobody was checking for subtle damage to tiny developing limbs, hearts or eyes.

Drug companies leaned hard into that gap. The ads promised peace, rest and relief for “tension” and morning sickness. Doctors handed the pills to pregnant women because they were told it was “non addictive” and “exceptionally safe.” Pharmacies even sold it over the counter in some countries.

On the surface, everything looked chill. People slept better. Nausea eased. No one yet realized that timing was everything. Scientists later figured out that if a pregnant woman took thalidomide during a narrow window, roughly between days 20 and 36 after fertilization, the drug could derail the baby’s early development. Limbs might not form fully. Ears, eyes or internal organs could be affected. The results were devastating.

By the time the pattern became clear, more than 10,000 children around the world were estimated to have been harmed. About 40 percent of them died around birth. Survivors often lived with shortened or missing limbs, joint problems, and serious health issues. Entire families were changed for life because someone trusted a pill that had not been properly tested.

While Europe and other parts of the world were swallowing this “wonder drug,” an American company was getting ready to cash in too. Richardson Merrell, based in Ohio, wanted to sell thalidomide in the United States under the brand name Kevadon. They filed an application with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, expecting a quick yes.

On paper, this looked like a done deal. The drug was already huge overseas. The company’s warehouses were stocked with millions of tablets. Christmas marketing plans were lined up. The FDA had only a handful of physicians reviewing every drug for the entire country, so most companies assumed the process would be more of a formality than a cross examination.

They had no idea who was about to review their file.

The New FDA Doctor Who Hit Pause

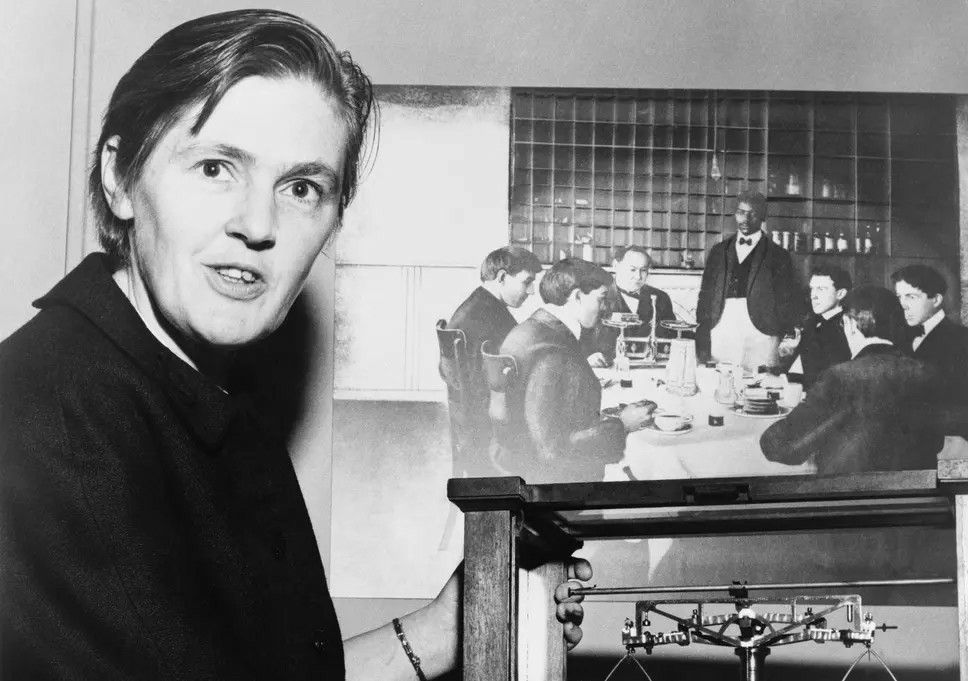

In 1960, Frances Oldham Kelsey walked into the FDA as a new medical officer. She had been there for barely a month when the thalidomide application landed on her desk. This was supposed to be her starter assignment. Other countries had already approved the drug, so her bosses expected a fast sign off.

Instead, she started reading, carefully.

The company claimed thalidomide was safe, but when Kelsey dug into the actual material, she found weak studies, messy animal data and almost nothing solid on pregnant women. Some of the glowing “evidence” looked more like marketing than real scientific evidence. There were no serious long term studies on fetuses at all.

Kelsey was not just some random bureaucrat nitpicking for fun. Years earlier, while working at the University of Chicago, she had studied how drugs travel through the bodies of pregnant animals and cross into embryos. She knew that medicine given to a mother could absolutely reach the baby. That knowledge sat in the back of her mind like a warning light.

So when she saw an application where a sedative was being pushed for pregnant women without strong data on unborn children, she got suspicious.

At the time, the law gave the FDA a weirdly short window. The agency had sixty days to raise objections. If nothing serious was raised, the drug could be approved by default. That meant speed usually benefited the companies.

Instead of rubber stamping the file, she sent the company a list of questions. She asked for more test results, more details on side effects, more proof that the drug was truly safe in pregnancy. The company sent back partial answers and testimonials. They leaned on the “but Europe is using it” argument.

Kelsey did not budge.

Every sixty days, when the clock was about to run out, she found legitimate reasons to ask for more information. Each time, the automatic approval was paused. Each time, company representatives grew more annoyed. They called her office constantly. They showed up in person. They complained to her supervisors that she was being unreasonable, that she was too rigid for a “rookie.”

She stayed calm. She stayed firm.

Then she saw something that made her even more uneasy. Reports were coming in from overseas doctors about patients who developed nerve problems after taking thalidomide for a while. Tingling, numbness, nerve damage in adults. If it could injure adult nerves, what would it do to a fragile developing baby brain and nervous system.

Kelsey asked for updated safety data. The company sent more positive stories instead of serious research. In their narrative, thalidomide was still the friendly sleep aid they wanted to flood across the United States.

She kept saying no.

This was not a movie style showdown. There were no dramatic speeches. It was one woman at a desk, reading files, writing letters, being pushed by a powerful company and choosing, again and again, to stick to the science she knew.

A Global Disaster, A Narrow Escape

While the arguments around Kelsey’s desk dragged on, the true horror of thalidomide was exploding in the rest of the world.

In Europe, Australia, Canada and other places where the drug had been fully approved, doctors started seeing more and more unusual birth defects. Babies were born with very short arms or legs, or missing limbs altogether. Some had issues with their ears, eyes or internal organs. The pattern took time to see, because these births were scattered across different cities and hospitals.

By the early 1960s, a few sharp doctors pulled the pieces together. They realized that many of the mothers had taken thalidomide early in pregnancy. What had been sold as a soothing pill for morning sickness had permanently changed the shape and health of thousands of children.

Countries scrambled to pull the drug off shelves. In West Germany and the UK, where it had been widely available, the scandal blew up into lawsuits, protests and intense public anger. People demanded to know how a supposedly safe medicine had been allowed into pharmacies without better testing.

Back in the United States, something strange stood out.

Almost no babies with thalidomide related defects were being born there.

Because Kelsey had never approved thalidomide, there was no nationwide rollout. There were no magazine ads loading it into every household. The drug was never legally on sale in American pharmacies.

That did not mean there was zero impact. While pushing for approval, Richardson Merrell had shipped out millions of sample tablets to more than a thousand U.S. doctors for “clinical trials.” Some pregnant women received the pills that way, even without formal approval. At least seventeen American children are known to have been born with defects linked to thalidomide. There were probably others who were never officially counted.

Still, compare that to thousands of affected children in 46 countries. The difference between American numbers and global numbers was dramatic. And it traced back to one doctor who refused to be rushed.

When journalists finally uncovered the details, the story blew up. A Washington newspaper ran a front page piece calling Frances Kelsey a hero who had quietly prevented a generation of damaged births. Regular people suddenly saw what someone inside a “boring” regulatory agency could actually do.

In August 1962, President John F. Kennedy invited Kelsey to the White House. In front of cameras and reporters, he awarded her the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service, the highest honour a civilian federal employee could receive. She was only the second woman ever to get it.

But the impact of her stubborn refusals went way beyond a medal.

The thalidomide crisis forced governments to admit that their old systems were not enough. In the United States, Congress passed the Kefauver Harris Amendment in 1962.

This law basically told drug companies: “Prove it.” From then on, they had to show that a new medicine was not just non lethal but actually effective and truly safe through solid clinical trials. They had to report side effects and use informed consent with people in studies.

Kelsey helped shape and enforce those rules. She later led teams that inspected drug trials and dug into sketchy data. Investigators who worked for her earned the nickname “Kelsey’s cops” because of how tough they were on sloppy science and hidden risks.

Instead of just stopping one dangerous pill, she helped redesign the entire game.

What Frances Kelsey Still Teaches Us

Kelsey stayed with the FDA until 2005, finally retiring at around ninety years old. By then, the landscape of medicine looked totally different from the world where thalidomide was first sold. Countries across the globe had tightened their drug approval systems, often directly because of the thalidomide scandal and the example set by people like her.

Ironically, thalidomide itself never completely vanished. Scientists eventually discovered that, under very controlled conditions, it could help treat certain cancers like multiple myeloma and serious complications of leprosy.

In the late 1990s, the FDA actually approved it for specific uses, but this time under intense safety rules. Patients have to enroll in special programs, use strict birth control, and take regular pregnancy tests. The same drug that once slipped onto shelves with barely any oversight is now locked behind layers of protection.

That shift is part of Kelsey’s legacy.

Her story also changed how we think about including women in research. For a while after the thalidomide disaster, regulators overcorrected and pushed women of “childbearing potential” out of early clinical trials. That caused its own problems, because medicines ended up being tested mostly on men and then prescribed to everyone. Eventually, policies changed again, pushing to include women in research responsibly, with better safeguards instead of exclusion.

Through all of that, Kelsey’s core principle stayed relevant. Do not let hype replace evidence. Do not confuse corporate confidence with actual safety. Do not assume that something is fine just because it is being used somewhere else.

She never invented a life saving drug. She did something less flashy and maybe even more important. She read the paperwork. She questioned the gaps. She refused to sign when the science was weak, even when that made her unpopular with powerful people.

You probably will not sit at an FDA desk deciding the fate of a global medicine. But you will face pressure to go along with the crowd, trust what is trending, or ignore your own sense that something does not add up.

Kelsey’s life is a quiet reminder that real courage can look like slowing down when everyone else is in a rush, asking boring questions, and saying no until the facts are clear.

Because she did that, thousands of children who would have been born with preventable injuries instead arrived in the world with healthy bodies and untouched futures.

Her story lives inside every prescription bottle that went through a real trial, every warning label that exists because someone refused to be fooled, every regulation that forces a company to test its claims before selling them.

The doctor who protected an entire generation of children did not save them with a miracle cure. She saved them with standards, with science, and with a word that most people hate to hear but absolutely need sometimes.

She said no. And for countless families, that small word made an entire lifetime of difference.

More Articles from this Publisher

What’s Really in Your Pepper? FIIRO Warns of Toxic Grinding Machines

Heavy metals from common market grinding machines may be entering everyday meals, with FIIRO linking the exposure to ris...

High-Income Careers That Don’t Require Traditional University Paths

Some of the highest-paying careers don’t care where you studied. Skills, results, and execution now open doors that dipl...

Was Santa Claus Really Copied from African Masquerades?

Was Santa Claus copied from African masquerade traditions? The claim sounds bold, but the historical record tells a diff...

How Many Mudashiru Ayenis Have We Buried, Or Tagged As "Mad"?

He built a robot at 20. Instead of applause, Nigeria sent him to psychiatrists. This is the story of Mudashiru Ayeni, th...

7 Countries Where Valentine’s Day Isn’t February 14

Valentine’s Day isn’t always February 14. Some countries mark love on entirely different dates, and the traditions behin...

Countries That Have Restricted Valentine’s Day Celebration

Valentine’s Day is global but not universally accepted. In some countries, February 14 has been restricted, discouraged,...

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...