The Population Plot Twist: What Really Changed in OECD Countries Since 1990?

Let’s say you wake up tomorrow and one out of every four people in your country was born somewhere else. Not visiting; living there. Working, paying rent, raising kids, arguing about the same sports teams, standing in the same grocery lines.

In several OECD countries, that is not a thought experiment. It is the lived reality, and it arrived fast enough that many people feel like it happened “to” them rather than “with” them.

The OECD produces regular, data-heavy reports on international migration flows, migrant labour, skills mobility, integration outcomes, and the fiscal impact of migration. One of its flagship publications is the International Migration Outlook, released annually, which tracks who is moving, where they are going, why, and how host countries are responding.

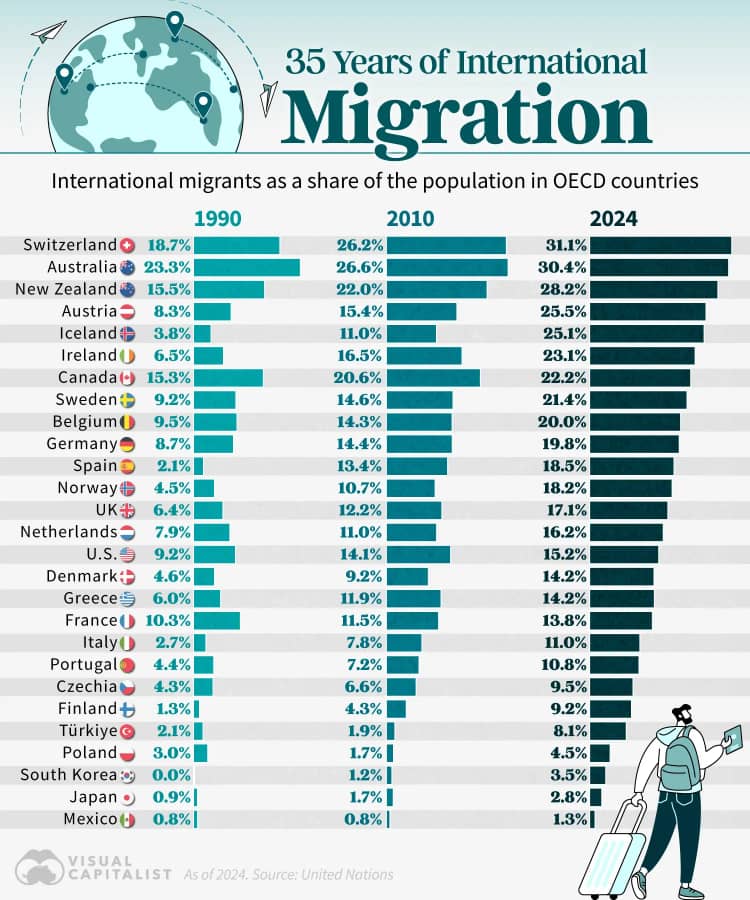

The Visual Capitalist infographic tracks the foreign-born share of the population in selected OECD countries across 1990, 2010, and 2024, using UN estimates.

The headline numbers are the kind that stick in your brain. Switzerland at 31.1% in 2024, Australia at 30.4%. New Zealand at 28.2%, Ireland at 23.1%. Germany at 19.8%, and Spain at 18.5% after being 2.1% in 1990.

You do not have to be “pro” or “anti” anything to recognize what that implies. That scale of change rewrites daily life. It changes what employers can do, what landlords can charge, what politicians promise, what schools need, and what the word “we” even means in practice.

Here is the provocative part, backed by the numbers: migration is no longer a side topic for many rich democracies. It is one of the main ways they are deciding what their future population and workforce will look like. The public argument, however, still treats it like a temporary border drama, or a morality play, or a culture war. That mismatch is exactly why the debate stays angry.

The Number That Sneaks Up On You

First, what are we actually counting?

The UN “international migrant stock” generally refers to people living in a country other than the one where they were born, based mainly on censuses and population registers. It is a stock measure, meaning it is a snapshot of who lives there, not a count of who crossed a border this year.

The OECD often uses a similar core concept when it reports on immigrants: the foreign-born population, regardless of citizenship. That distinction matters more than people realize.

When someone hears “migrant,” they may picture someone who arrived recently. But a foreign-born share includes the nurse who moved 15 years ago and is now a citizen. It includes the classmate who arrived at age two.

It includes the engineer recruited by a company, the student who stayed, the person who joined family, and refugees who were resettled. This is not a measure of legality or “newness.” It is a measure of how internationally mixed a country’s resident population has become.

Now zoom out.

Diaspora Connect

Stay Connected to Home

From Lagos to London, Accra to Atlanta - We Cover It All.

Globally, the UN estimates about 304 million international migrants in mid-2024, about 3.7% of the world population. If you stop there, migration sounds small. The trick is concentration. A small global share can still mean very large national shares in particular countries, especially wealthy, stable ones.

That is the first reason this topic feels so intense. People argue as if every country is dealing with the same situation. They are not. A country with 3% foreign-born is playing a different game than one with 30%.

The second reason is timing. The human brain is not great at noticing gradual shifts until they become obvious. Ten years pass. Suddenly the workforce, the classroom, and the neighborhood are visibly different. Then the debate starts, but it starts late, and it starts emotional.

That does not make anyone stupid. It makes them human.

Three Migration Stories Hiding Inside One Statistic

One number can still hide three completely different national stories.

Story one: “We have done this for a long time.”

Countries like Australia, Canada, and New Zealand have high foreign-born shares and long-standing systems for settlement and integration. The point is not that everything is perfect.

The point is that institutions have repetition. They have had to learn how to handle credential recognition, language learning, citizenship, and discrimination over decades, not just during spikes. The foreign-born share is part of how these countries work, not a surprise bolt from the sky.

Story two: “We changed fast, then argued about it later.”

Parts of Europe look like rapid transformers. Spain is the most dramatic example in the infographic: from 2.1% foreign-born in 1990 to 18.5% in 2024. Ireland also jumps sharply to 23.1%.

These are not gentle transitions. These are changes that happen within a single generation.

When change is that fast, it is not only about how many people move in. It is about whether housing, public services, and politics adapt at the same speed.

Europe also has a twist that confuses the debate: a lot of movement is within Europe. Under the UN definition, a person born in one European country and living in another counts as foreign-born, even if they moved under rules of free movement rather than a classic immigration system.

So some demographic change comes from mobility among neighbours, not only from far-away migration. The politics often ignores that, because the political story wants one simple villain.

Story three: “We stayed low, and paid a different price.”

Countries like Japan and South Korea remain low in the infographic, though their shares rise. Japan is 2.8% in 2024. South Korea is 3.5%. You can have a high-income economy without a huge foreign-born share, but you do not get that choice for free.

Low migration countries face sharper pressure from aging, tighter labour markets in certain sectors, and hard decisions about workforce participation and productivity.

Diaspora Connect

Stay Connected to Home

From Lagos to London, Accra to Atlanta - We Cover It All.

The OECD puts some of this in blunt terms: across the OECD, the foreign-born share is over 10% and rising in most members, with some countries far higher and a small group still below 3%. In other words, countries are not converging toward one model. They are making different demographic bets.

So the real question becomes: what are they buying with those bets, and who gets the bill?

The Real Fight Is Over Space, Not Passports

Migration politics often sounds like it is about identity. A lot of it is actually about scarcity.

If a city has enough housing, adding people is easier. If a city already has a housing shortage, adding people turns daily life into competition. Renters feel it first, even new graduates feel it.

Families feel it when the nearest school is full. Patients feel it when clinics are booked. If governments do not expand capacity, people experience migration as being pushed out of their own lives.

That is why the debate stays hot even when economists can show benefits in the aggregate. Benefits are often spread out, costs are often concentrated; and employers may love a larger labour pool. Homeowners may enjoy rising property values. But renters, lower-wage workers, and strained neighbourhoods absorb the friction.

There is also a credibility gap. When leaders say, “Migration is good for growth,” but the visible reality is “I cannot find an apartment,” the public hears the message as: “Your pain is the price of someone else’s plan.” That feeling is political gasoline.

And yes, there is a demographic driver underneath all this: wealthy societies are aging. Migration becomes one of the few levers that can change the working-age population faster than birth rates can. This is not a secret. It is one reason OECD migration flows have remained high in recent years, with mixes of work, family, humanitarian, and other channels.

The provocative claim that many people sense, but few say out loud, is this: in some places, migration has become a substitute for fixing deeper problems.

If a country underbuilds housing for 20 years, then increases population quickly, it gets chaos. If a country underinvests in training nurses and caregivers, then recruits abroad at scale, it patches the staffing crisis without repairing the pipeline. If a country avoids productivity reforms, migration can keep the economy looking “fine” in headline GDP while living standards feel stuck for many people.

None of this means migration is “the problem.” It means migration amplifies whatever a country refuses to fix.

So when people ask, “Why is the debate so bitter?” the honest answer is: because it is not only about who is arriving. It is about whether the system is fair and whether anyone is in charge.

Conclusion

Migration is not a weather event. It is a choice, or a series of choices, shaped by labour demand, humanitarian obligations, demographics, and politics. The last 35 years show that many OECD countries made big choices quietly, then fought loudly afterward.

Diaspora Connect

Stay Connected to Home

From Lagos to London, Accra to Atlanta - We Cover It All.

The next 35 years will be harder, not easier. Global displacement pressures, economic inequality, and aging populations are not fading away. The only way the debate becomes less toxic is if governments stop pretending migration is a temporary controversy and start governing it like the permanent reality the numbers already show.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...