The Next Big Discovery Might Be Growing in Someone’s Backyard

In a quiet village in Kenya, a young botanist bends over a patch of wild herbs. To most eyes, it’s just another weed sprouting through red soil after the rains. But to her, it’s a clue, a species that might hold the next breakthrough in natural medicine. Across the world, from suburban backyards in Texas to small farms in Ghana, a new truth is emerging: innovation no longer lives only in laboratories. Sometimes, the next great scientific leap begins in the most ordinary of places; someone’s backyard.

The Science Hidden in Plain Sight

Throughout history, the boundary between the natural world and the laboratory has been porous. The penicillin that revolutionized modern medicine came from mold on a petri dish. The CRISPR gene-editing system, one of the most powerful discoveries in biology, was inspired by a natural bacterial defense mechanism. Science has always borrowed from what the earth offers but now, a new wave of researchers and citizen scientists are rediscovering what might be the greatest lab of all: nature itself.

In Nigeria, researchers at the National Biotechnology Development Agency (NABDA) have been studying native plants for compounds that could treat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Across the border in Ghana, scientists at the Centre for Plant Medicine Research are blending traditional herbal knowledge with clinical trials to identify natural antivirals. These are not grand research parks or billion-dollar facilities; they’re modest spaces where curiosity meets patience and sometimes, breakthroughs happen.

As global research funding tightens, more innovators are turning to what they already have their surroundings. The rise of DIY science and community labs has democratized experimentation. In Cape Town, the open lab BioRoboTech offers local enthusiasts access to microscopes and mentorship, proving that scientific curiosity doesn’t require a PhD, just persistence.

According to Dr. Katlego Mogale, a molecular biologist at the University of Pretoria, “We’re entering a period where the citizen scientist has power. What once required a university can now begin at home with the right discipline and data.”

Her point underscores a quiet revolution. From backyard composting experiments that uncover new soil microbes to homegrown aquaponics systems improving food sustainability, backyards have become the incubators of discovery.

WorkAfrica’s landscapes are overflowing with potential, often under-researched and undervalued. According to a report from the African Academy of Sciences, less than 1% of global research on medicinal plants focuses on African species, despite the continent hosting a third of the world’s biodiversity.

One striking example is the Artemisia annua plant. Native to China but cultivated in East Africa, it became the foundation of artemisinin, one of the most effective antimalarial drugs ever discovered, a reminder that the next cure might already be growing underfoot.

In Nigeria’s Niger Delta, scientists are now studying mangrove species for their potential to absorb heavy metals and purify polluted water. The goal isn’t just environmental recovery but sustainable chemistry, a bio-based future rooted in African ecosystems.

The Digital Age of Discovery

Technology has amplified what a backyard scientist can do. With smartphones capable of macro photography, soil-testing apps, and open databases like GBIF, data collection and sharing have become accessible to anyone with curiosity.

Citizen science platforms such as iNaturalist allow people to upload photos of plants, insects, and fungi, helping professional researchers identify and map species in real time. What once required institutional resources can now be achieved through crowdsourcing and collaboration.

Professor Lucy Kimani, an environmental scientist at the University of Nairobi, explains: “We’re seeing a new model of discovery decentralized and inclusive. Someone in a village can collect data that ends up in a global biodiversity report. That’s power.”

It’s a reminder that knowledge no longer flows in one direction from the lab to the world but in loops, from communities to data centers and back again.

When Tradition Meets Science

In many African communities, traditional healers have long been custodians of natural knowledge. The roots, leaves, and barks they use often hold real pharmacological potential only recently validated through modern methods.

The collaboration between traditional medicine and modern science is not new. The World Health Organization (WHO) has long supported integrating traditional knowledge into formal healthcare systems, provided there’s rigorous testing and documentation. But what’s new is the mindset: researchers are beginning to see these indigenous systems as sources of innovation, not superstition.

In Uganda, local communities are partnering with scientists to document indigenous plant use for climate resilience. Farmers are identifying drought-resistant crops based on ancestral knowledge, feeding data into research at the Makerere University College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

Some of today’s most surprising innovations began outside formal labs. The Aloe Vera-based biofuel developed by South African students started as a university garden project. In Kenya, a farmer experimenting with mushroom waste ended up discovering an eco-friendly alternative to styrofoam packaging.

Such grassroots projects illustrate a powerful truth: innovation isn’t always about cutting-edge technology. It’s about curiosity, persistence, and the willingness to observe.

In fact, a 2023 report from the UNESCO Science Report found that community-led research initiatives in Sub-Saharan Africa have grown by 40% in the past five years. This signals not just participation, but leadership a new form of discovery rooted in proximity and purpose.

The Economics of Everyday Innovation

For years, funding has been concentrated in elite institutions, but that’s beginning to change. Programs like the African Union’s Innovation Fund and Google’s AI for Social Good initiative are supporting small-scale inventors and researchers tackling local challenges.

These shifts matter because innovation doesn’t thrive in isolation. It needs ecosystems of policy, mentorship, and public trust. The fact that a backyard garden can yield a scientific paper or a patent shows how democratized knowledge has become.

Still, challenges remain: lack of funding, poor documentation, and limited access to research tools. But as the open science movement grows, so too does the possibility that the next breakthrough will come from somewhere unexpected.

The climate crisis has only heightened the urgency for local innovation. Scientists are now studying climate-smart crops like millet, cassava, and moringa plants that have adapted over centuries to harsh African conditions.

According to a 2024 study by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), backyard gardens and smallholder farms contribute more than 60% of Africa’s agricultural biodiversity. That makes them not just food sources, but living laboratories for climate adaptation.

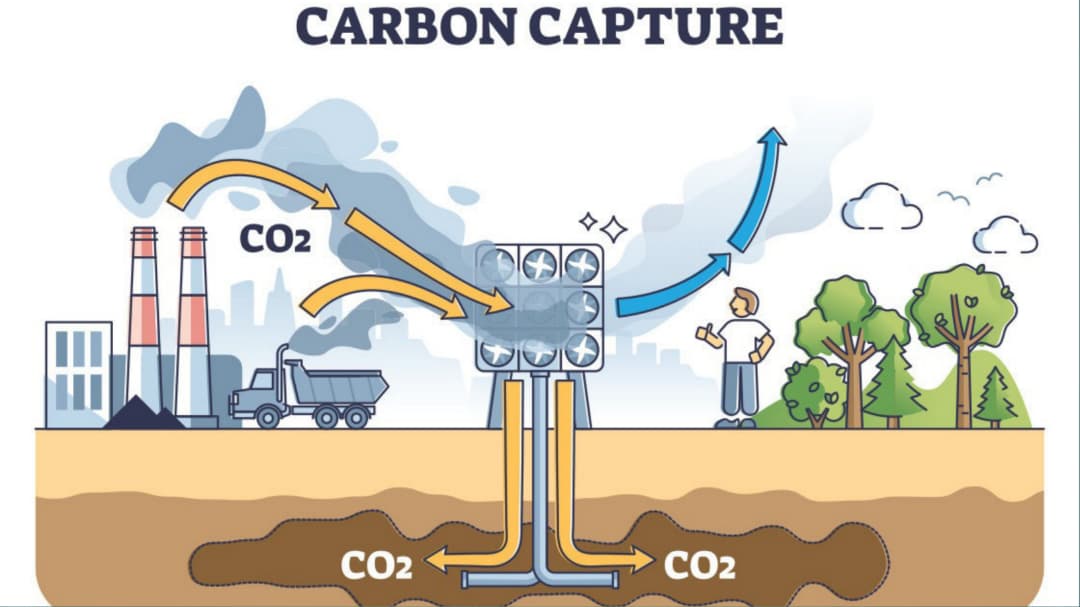

The next big agricultural discovery from carbon-sequestering crops to drought-tolerant species may already be germinating quietly behind someone’s house.

Redefining Who Gets to Be a Scientist

The myth of the lone genius in a white coat is fading. In its place, we’re seeing networks of teachers, farmers, students, and tinkerers people who see the world not as finished, but full of possibilities. The future of science isn’t locked away in research centers. It’s in communities. It’s in backyards. It’s in the hands of people who pay attention.

That’s perhaps the most radical idea of all; that the act of noticing, of being curious about the everyday, might be enough to change the world.

So the next time you walk through a garden, look at a weed, or glance at a patch of moss growing on the wall, remember: the line between ordinary and extraordinary has always been thin. The great innovations of tomorrow might not come from glass towers or billion-dollar budgets, but from the quiet persistence of observation in a backyard, a school garden, or a farmer’s field.

Because sometimes, the next big discovery isn’t waiting to be invented. It’s already here, growing in someone’s backyard.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...