NanoFilter: The Tanzanian Invention Turning Dirty Water into Life

Introduction

Across rural Tanzania, the morning rituals were usually predictable: girls and women shouldering buckets and cans, tracing dirt tracks to riverbanks while the sun rose. Moving and struggling along different paths with water that shimmered like a promise, but in all of this, there was an invisible danger: bacteria, parasites, heavy metals, and disease. It is a picture that is painfully familiar not only in Tanzania, but in rural communities across all of Africa. Yet from that everyday struggle, an invention was born, with the quiet power of a revolution: the NanoFilter, the low-cost, locally adapted water purifier developed by Tanzanian scientist Dr. Askwar Hilonga.

The NanoFilter’s story is both plainly human and quietly scientific, a blend of childhood memory and laboratory rigor. For millions, it is the difference between a week of bartered medicine and a week of healthy school attendance. For development actors, it is proof that African problems can be solved with African ingenuity.

A Childhood Promise Turns Into Purpose

Askwar Hilonga was born in a place where access to clean water was not guaranteed. He watched families fall sick. He watched opportunity shrink when illness struck the working age. That childhood view, that safe water should not be a luxury, became the foundation for his life’s work.

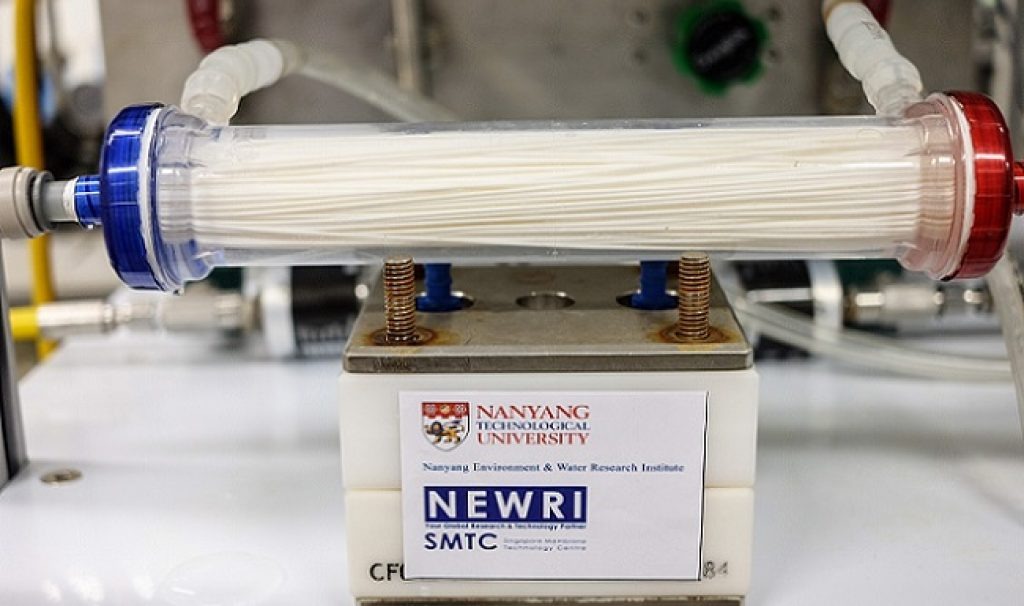

After receiving an education in chemical engineering and nanotechnology, Hilonga returned to Tanzania and focused on a practical question that plagued his community: how to design a water-treatment system that costs little, uses locally available materials, and can be tuned to the contaminants actually found in local wells and boreholes. The result: the NanoFilter, which combines traditional filtration materials with engineered nanomaterials that target specific toxins and microbes. The system is not a glossy import; it is built to fit local needs.

How NanoFilter Works — Science That Fits the Village

At the very basis, the NanoFilter is an innovation that is a layered approach. Sand and activated carbon remove sediment and large impurities; nanomaterials, tiny engineered particles measured at billionths of a meter, adsorb or neutralize contaminants such as bacteria, viruses, fluoride and heavy metals like arsenic. The trick is precision: the filter can be customized depending on what tests of local water reveal.

Unlike many solutions that fail because they require expensive replacement parts or complex maintenance, NanoFilter kiosks are designed for modest upkeep using locally sourced components. The technology can meet WHO drinking water guidelines for contaminants when properly operated, and the kiosks are run as community water points or micro-enterprises so local residents can afford safe water without unsustainable subsidies.

The Human Impact: Health, Dignity, Opportunity

Technology without human effect is only a novelty. With NanoFilter, the effect is immediate and measurable in daily life. With the assurance of safe water at various communities, the first visible result was fewer reports on diarrhoea and typhoid. Children missed fewer school days; household spending on medicine fell. Mothers described a freed rhythm: less time spent on ill children, more time for income-generating work.

Public health agencies long emphasize that safe water and sanitation are foundational to health. UNICEF and the World Health Organization consistently underline that access to clean drinking water reduces child mortality, improves nutrition, and increases school attendance. The NanoFilter doesn’t solve all problems at once, but it addresses one of the most basic determinants of well-being: reliable, clean water close to home.

Hilonga didn’t limit his vision to a lab prototype. He built a model for scale: community water distributions run by local entrepreneurs, often women, who are trained not only in filter maintenance but in basic business skills. Charging a token fee per container, usually far less than the combined daily cost of fuel, medicine, or transport, made kiosks financially sustainable while putting ownership in local hands.

That micro-franchise model matters. It transforms recipients into stewards. Women who run kiosks earn income and gain social standing. Local technicians learn to service units. The system becomes part of the local economy, not an external charity that dries once donor attention wanes.

Recognition And New Realities

The NanoFilter’s success brought recognition, it's a proof that Africans can provide solutions that meet their local needs and do not need to be dependent on foreign aids. Hilonga won prestigious innovation awards that raised the profile of the invention internationally. Yet recognition alone does not solve the tougher problems of scaling manufacturing, securing long-term finance, and integrating solutions into national water strategies. Hilonga’s journey shows the classic arc of African innovation: bright ideas, local proof, and then the struggle to scale within ecosystems that still favour imported solutions.

On that front, the NanoFilter faces familiar barriers: fragile supply chains, limited local manufacturing capacity for nanomaterials, and the need for investment to reach remote communities. There’s also a knowledge gap: national water ministries and donors must be convinced not just by prototypes but by long-term monitoring data on health outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

Why This Matters for Africa, Beyond a Single Invention

Why celebrate one filter? Because the NanoFilter represents a change in narrative. For too long, the story of development in Africa has been told as a top-down tale: western experts diagnosing, foreign technology rescuing. NanoFilter flips that story: a Tanzanian scientist draws on personal experience and technical skill to create a solution that fits the social, cultural and economic reality of his country.

Moreover, the filter model highlights a critical principle for development: contextualization. A technology that works when it is shaped by the people who will use it and operated by them, has far better odds of lasting impact. In practical terms, that means designing for local maintenance, using local materials where possible, training local technicians, and embedding solutions in livelihoods.

The Health Imperative — WHO and UNICEF’s Signal

Large global health bodies repeatedly remind us that safe water, sanitation and hygiene are not optional extras; they are essential. WHO and UNICEF report that contaminated water contributes to a significant share of diarrhoeal disease and child mortality worldwide, and that improvements in water quality are among the most cost-effective health interventions. Those institutions also stress that sustainable water access must go hand-in-hand with community ownership and behaviour change, the exact priorities the NanoFilter model embraces.

When international agencies say that water is life, inventions like NanoFilter show how that life can be protected, starting with low cost, locally governed interventions that close the gap between policy rhetoric and daily reality.

Real Challenges: Maintenance, Finance, and Trust

No innovation is a magic wand. For NanoFilter to reach millions, systems must be in place: reliable supply chains for replacement media, financing for kiosk rollout, quality control to ensure each unit delivers safe water, and community education to prevent unsafe recontamination.

Trust is another hurdle. Communities that have been burned by failed interventions and doubts in local inventions are understandably cautious. Hilonga’s approach, training locals to run the kiosks and making the operation transparent, helps build trust, but scaling trust is slow work.

The NanoFilter story offers lessons for policymakers. First, invest in local R&D and make it easy for innovators to prototype and manufacture at home. Second, link health outcomes to innovation policy: prioritize technologies that address immediate public health burdens. Third, design procurement and financing systems that favour locally adapted solutions, including social enterprise models that combine impact with sustainability.

If ministries and investors took such steps, the continent could accelerate solutions developed for its own realities rather than importing mismatched technologies.

Conclusion: One Drop, A Thousand Ripples

When people drink safely from a NanoFilter kiosk, they are not just hydrating. They are accessing dignity, opportunity and time. A mother who no longer spends money on repeated clinic visits can start a small business. A child who misses fewer school days gains a chance at education. These are the cascading returns of a small but powerful idea.

The NanoFilter is more than an engineering success. It is a moral argument: that local genius, applied to local problems, can outcompete the best-meaning foreign prototype. Hilonga’s invention reminds us that the future of development may well be found in the innovation of our hands and in the tenacity of inventors who refuse to accept the unacceptable.

If Africa wants to change the everyday realities of its people, it must do more than celebrate innovations, it must build the ecosystems that let those inventions breathe, scale and last. Otherwise, life-saving ideas will remain sparks rather than flames.

For now, in village after village, the NanoFilter is doing what great inventions do: quietly improving lives, one drop at a time.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...