Love And Genetics: Darwin’s Personal Experiment

Introduction

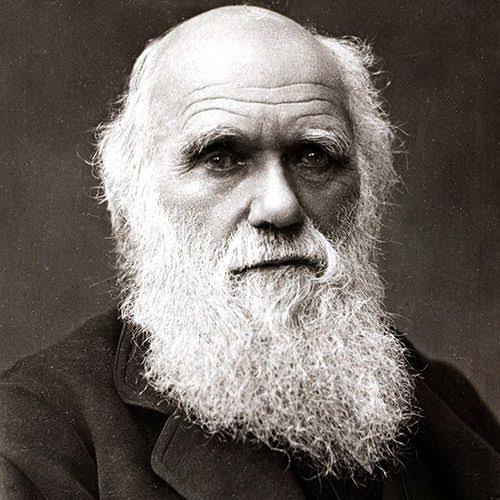

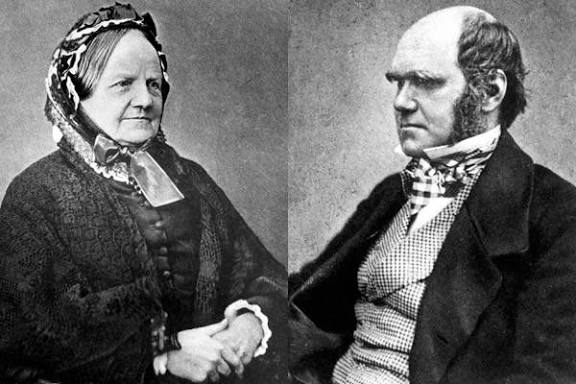

Charles Darwin is remembered for revolutionizing biology, reshaping humanity’s understanding of evolution, and laying the foundations for modern genetics. Yet, behind the grand theories and groundbreaking studies, there was a deeply personal story—one intertwined with family, marriage, and loss. Darwin married his first cousin, Emma Wedgwood, in 1839, and together they had ten children. But the joy of family life was tempered by tragedy: three of their children died before reaching ten, and several others faced health complications. These personal hardships, some historians argue, may have shaped not only Darwin’s intellectual curiosity but also his pioneering investigations into the effects of inbreeding.

This raises a curious question: would Darwin have conducted his experiments on inbreeding if his own family had not experienced such health challenges? Was the cornerstone of genetics partly born from personal grief and familial observation?

Darwin’s Marriage: Love, Loss, and Scientific Curiosity

Darwin’s marriage to Emma Wedgwood was a union of affection and family ties. In 19th-century England, cousin marriages were not uncommon among certain social classes. They were often motivated by the desire to preserve wealth, status, or familial alliances. Darwin himself was deeply in love with Emma, and their relationship was a genuine partnership of minds and hearts.

Yet, the union also brought personal sorrow. The premature deaths of three children and the chronic illnesses of others placed Darwin in a position many parents dread: witnessing the fragility of life within his own household. Notably, his son Leonard struggled with fertility issues and never had children, despite marrying another cousin later in life. These patterns of ill health and reproductive difficulty were not lost on Darwin, who was both a keen observer and a methodical thinker.

Darwin’s personal experiences may have prompted him to ask scientific questions others might have overlooked: Does marrying within a close family affect the health and survival of offspring? Or maybe not and if so, how, and why? His curiosity was not merely academic; it was deeply personal.

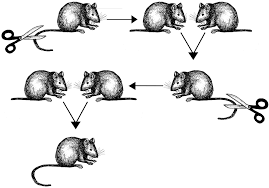

Inbreeding and “Inbreeding Depression”: Scientific Insights from Pain

Darwin extended his familial observations to scientific experiments, notably with plants. By studying the effects of self-fertilization, he documented what came to be known as “inbreeding depression”, a reduction in biological fitness due to closely related parents. Darwin’s experiments demonstrated that progeny from closely related parents tended to be weaker, less fertile, and more susceptible to disease than those from genetically diverse pairings.

These findings had profound implications. Not only did they illuminate fundamental principles in genetics and evolution, but they also contributed indirectly to the understanding of human reproductive health. It is intriguing to consider that these insights, which have influenced generations of biologists and medical researchers, may have been partially inspired by the misfortunes within his own household.

It leads one to wonder: if Darwin had not faced health challenges in his children, would he have pursued these experiments with the same vigor? Could it be that the foundations of genetics were partly shaped by personal grief, a curiosity born from the intimate sphere of family life? The question blurs the line between personal experience and scientific objectivity, illustrating that even the most rigorous scientific investigations are, at times, inseparable from human context.

Family, Culture, and the African Perspective

Across much of Africa, the idea of marrying a close relative, particularly first cousins is often met with caution or outright taboo. While cultural norms vary from one ethnic group to another, many African societies discourage intra-family marriages due to the perceived risks of health complications, genetic disorders, and social disruptions.

Anthropologists note that these prohibitions are often reinforced by traditional knowledge systems, which emphasize the health of the offspring and the stability of extended family networks. In societies where family cohesion is paramount, the risks associated with consanguineous unions are seen as a threat not only to the individuals directly involved but also to the broader social fabric.

This African lens highlights an intriguing contrast with Darwin’s context. In 18th-century England, cousin marriages were socially acceptable and sometimes strategically advantageous. In much of Africa, however, the cultural ethos prioritizes genetic diversity within family structures, even when love is present. The tension between personal choice and societal expectation is especially pronounced when affection defies cultural boundaries.

Does True Love Defy Genetics?

Darwin’s marriage raises an age-old question: can true love, when it crosses familial boundaries, justify potential risks to offspring? History shows that love and attraction do not always align with genetic prudence. Across time and geography, couples have faced this dilemma.

Yet, the African perspective underscores that love cannot exist in isolation from communal and cultural responsibilities. Marriages are not purely private affairs; they carry implications for children, families, and communities. When love intersects with genetics, the stakes are high, particularly in societies with limited access to advanced medical care.

Darwin’s situation illustrates a delicate balance: his affection for Emma was genuine and profound, yet it came with unforeseen consequences for their children. It is a reminder that love, while powerful, does not exempt us from biological realities. In African societies, such awareness is woven into cultural practices, reinforcing the principle that the well-being of offspring must be prioritized alongside the happiness of parents.

Also while many may argue that love may defy genetics, the outcome of this relationships are usually palatable, imagine two individuals with with both genotype of AS, it is only by some miracles that they don't give birth to a sickle cell child, but the possibility of it happening is certain; so does true really defy genetics

The Legacy of Personal Experience in Science

Darwin’s exploration of inbreeding exemplifies a broader truth in science: personal experience often catalyzes inquiry. Observing health challenges among his children may have sharpened his curiosity about heredity and biological fitness, motivating experiments that would later inform evolutionary biology, genetics, and medicine.

Consider the broader implications. Many scientific discoveries are inspired, in part, by personal encounters with disease, social issues, need to make life easier or familial patterns. The human experience, our joys, sorrows, and observations provides the raw material for questions that drive research. Darwin’s life reminds us that science is not conducted in a vacuum; it is intimately connected to the lived experiences of researchers.

Ethical Reflections: Balancing Love, Culture, and Genetics

Darwin’s story also invites ethical reflection. If one were to transpose his situation to modern Africa, questions about cousin marriages would emerge in a sharper light. Would health authorities, family elders, or cultural norms intervene? How would communities balance the couple’s emotional bond against the potential risks to their children?

These questions are particularly relevant in Africa, where traditional knowledge and modern medical understanding often coexist in complex ways. While genetic counseling and medical advice can mitigate risks, cultural values still strongly influence marriage decisions. Darwin’s experiences thus offer a lens through which we can explore how societies navigate the tension between personal freedom, familial love, and biological responsibility.

Charles Darwin’s marriage to Emma Wedgwood, and the health challenges they faced, reveal a fascinating intersection of love, culture, and science. While Darwin’s experiments on inbreeding laid the groundwork for genetics and medicine, one cannot help but ponder whether personal hardship catalyzed his scientific curiosity.

In Africa, where cousin marriages are often discouraged, Darwin’s story sparks reflection on the complex interplay between cultural norms, personal choice, and biological realities. True love, as history shows, does not always conform to genetic prudence. Yet societies have long recognized the importance of balancing emotional desire with communal and familial responsibilities.

Darwin’s legacy, therefore, is twofold: he contributed foundational knowledge to science, and he offered a human story that reminds us how personal experience can inspire profound discovery. His life encourages curiosity about the origins of scientific inquiry, the ethics of family, and the ways in which culture shapes our understanding of love, responsibility, and health.

In the end, Darwin’s tale is a curious lens on humanity itself—where love, loss, science, and culture intersect to produce insights that transcend time and geography.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...