Born to Live Less? The Global Life Expectancy Map and What It Says About Africa

Why Some Lives Are Longer Than Others: A Global Mirror with an African Frame

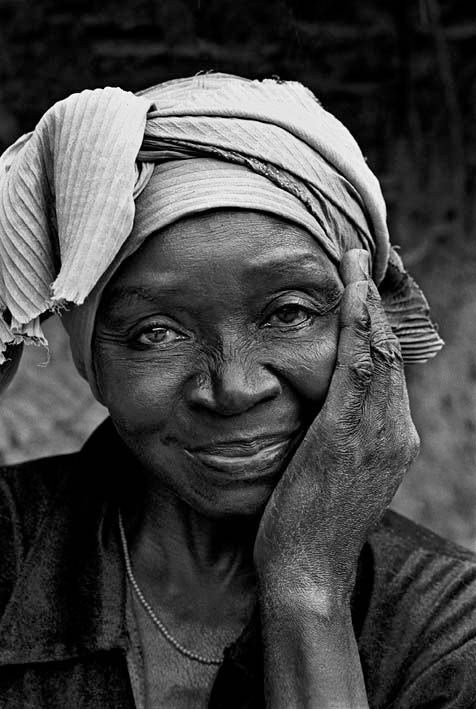

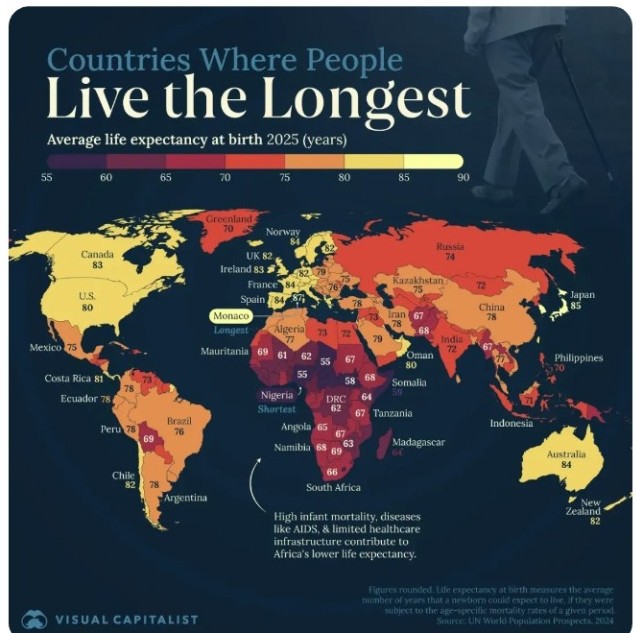

When a child is born in Monaco, they can expect to live nearly 90 years in a world where, just decades ago, reaching 40 was considered fortunate. But in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, a newborn may face a harsh reality — the expectation of living barely past 55. These stark contrasts are laid bare in a Visual Capitalist map released in mid‑2025, which colours countries by average life expectancy at birth.

Far from being mere numbers, these lifespans represent diverse histories, policies, cultures, economies, and access to healthcare. The map doesn’t just chart life expectancy; it forces an uneasy reflection on what it means for our place of birth to determine our chances in life. For us in Africa, it’s an urgent call to reimagine public health, shift policy from survival mode to sustainability, and challenge the assumption that long life is a Western luxury.

While global average life expectancy reached 73.49 years in 2025, according to MacroTrends and UN World Population Prospects, Africa still struggles at the bottom of the ladder. IHME projects a five-year global gain by 2050, but will Africa be part of that success story?

Copenhagen to Kano: Where Long Life Lives and Where It Doesn’t

At the top of the ladder, Monaco leads with a jaw-dropping 90-year life expectancy. Close behind are Japan (85 years), Switzerland, Iceland, and Norway, all boasting universal healthcare, low violence, well-paying jobs, and clean air. These are societies built to support aging well, physically, mentally, and financially.

Even mid-tier nations like Canada (83), New Zealand (84), and Costa Rica (81) are showing that smart policy can buy time. Their longevity isn't magic; it's governance with a human soul.

Meanwhile, back home, only a few African nations like Tunisia (77), Mauritius (75), Cabo Verde (76), and Algeria are nudging the global average. As Intelpoint’s 2024 data shows, these countries prove that Africa’s life expectancy problem isn’t destiny — it’s policy.

Contrast that with Nigeria (56 years), Chad (55), South Sudan, and Somalia. Nigeria, with all its oil wealth, remains last in global rankings, as highlighted by the Africa Health Report. The problem isn’t money; it’s mismanagement, poor healthcare access, and weak insurance coverage. Barely 5% of Nigerians have health insurance.

The African Angle: Why the Continent Can’t Afford Shorter Lives

Africa is the youngest continent in the world, bursting with potential, yet bleeding time. The low life expectancy isn’t just a health crisis; it’s a productivity nightmare, a talent tragedy, and a loss of generational wisdom. Every year that is shaved off our collective lifespan is a year stolen from innovation, governance, and culture.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

It also widens inequality. While countries in the Global North plan for centenarian populations with pension funds and robot caregivers, Africa grapples with malaria, maternal mortality, and poor sanitation. In Nigeria, a pregnant woman faces a higher risk of dying in childbirth than her counterpart in Scandinavia does of dying at 80.

But it’s not all gloom. Rwanda’s healthcare model, Ghana’s digitized NHIS, and Ethiopia’s community health extension workers show that African nations can build life-extending systems with limited resources. We need to scale what works and stop romanticizing resilience. Africans deserve to live long, not just survive long enough to bury their dreams.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

The Future of African Life: From Data to Dignity

Data tells us something deeply human: where you are born determines how long you’ll live. But it doesn’t have to stay that way.

To close the gap, Africa needs more than sympathy; we need systems. More investment in primary healthcare, smarter malaria control, and universal vaccination. We need to fund hospitals before elections and build policies that survive after them.

Education, especially female education, is a proven health booster. Similarly, this includesnutrition,clean energy, andtransportation. Governments should not just promise reforms; they must audit every budget to assess its impact onlife expectancy.

The final hope? That in a decade or two, a child born in Ibadan, Nairobi, or Kigali will have the same life odds as one born in Zurich. And that when the next Visual Capitalist map is published, the red fade of short life won’t blanket Africa anymore, but shimmer with golden years earned, not borrowed.

Because in the end, long life is not a luxury; it’s a right. And that right belongs everywhere, including here.

Cover Photo: From Pinterest

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...