Africa's Greatest 'What If': When the Continent Tried to Become One Country

Could Africa have become a single country—one flag, one government, one destiny? This was not just a rhetorical question in the 20th century.

For many African leaders and thinkers, especially in the wake of colonialism, the idea of a united Africa wasn’t a fantasy—it was a political goal.

From bold speeches to continental summits, the ambition to create a "United States of Africa" once stirred the hearts of a generation.

The Pan-African Vision: One Africa, One Nation

Pan-Africanism, the movement for the unity of African people worldwide, gained traction in the early 20th century, championed by intellectuals and leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and later, Kwame Nkrumah.

For them, unity was the only shield against neocolonialism, foreign domination, and the economic fragmentation left by European powers.

Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), proposed a “Back to Africa” movement and envisioned a global Black empire.

His ideas, while controversial, deeply influenced African nationalists. Du Bois, an African-American scholar and activist, pushed for Pan-African congresses in the early 1900s that brought African leaders and diaspora intellectuals together to strategize Africa’s political future.

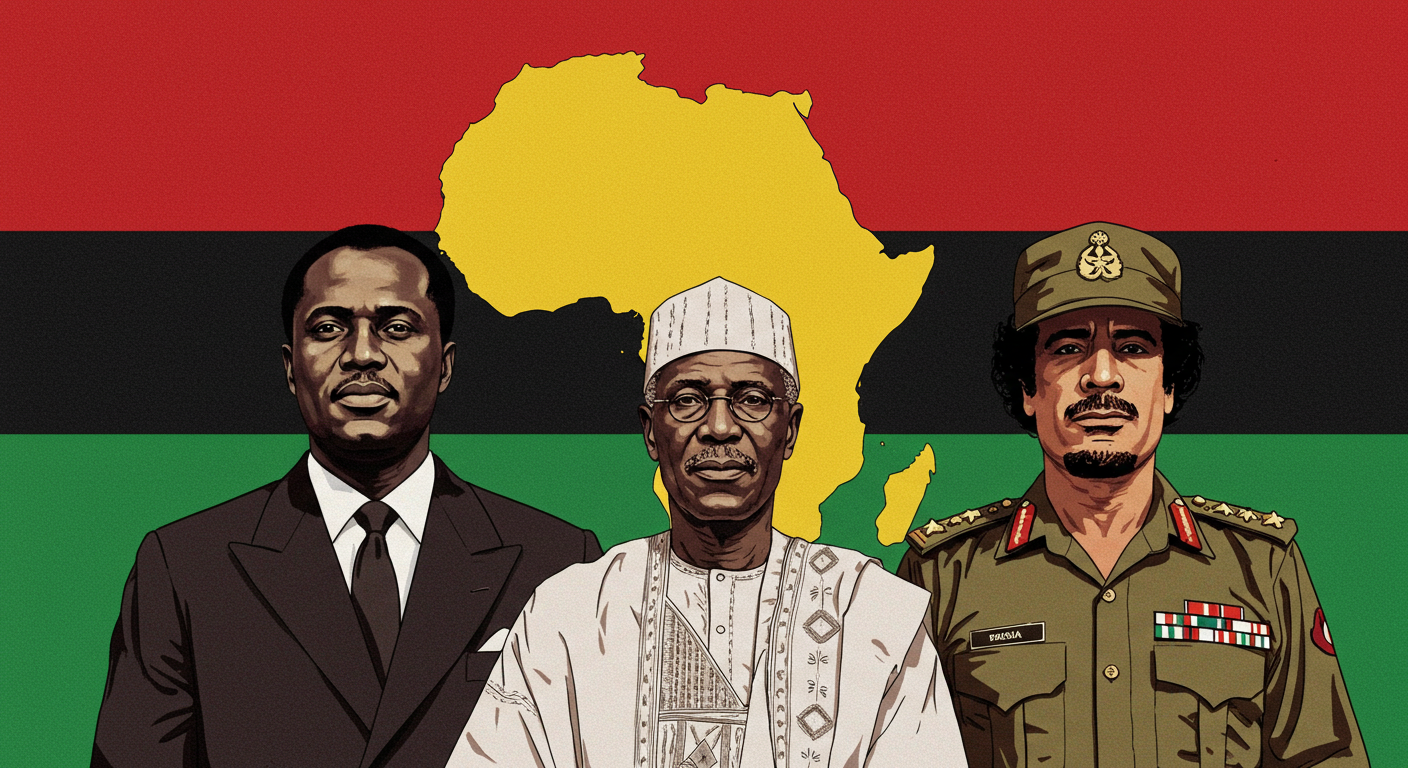

Kwame Nkrumah: The Architect of African Unity

No leader believed in African unity more passionately than Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah. After leading Ghana to independence in 1957—the first sub-Saharan country to do so—Nkrumah quickly set his sights on continental liberation.

In 1963, at the founding summit of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa, Nkrumah declared:

“Africa must unite or perish.”

He proposed an immediate political federation: one army, one currency, one central bank, and one foreign policy. For Nkrumah, only a united Africa could resist Western economic manipulation, build strong institutions, and develop at scale.

He believed that fragmentation weakened the continent, making it vulnerable to foreign powers and economic exploitation.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

To him, Africa’s wealth—its gold, oil, cocoa, bauxite, and workforce—was being siphoned off by outsiders precisely because African states were too divided to act in their collective interest.

But not everyone agreed.

The Casablanca vs. Monrovia Bloc: A Continental Split

At the heart of the disagreement were two ideological camps:

The Casablanca Group: Led by Nkrumah, Sekou Touré (Guinea), and Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), this group pushed for immediate union and a single continental government.

The Monrovia Group: Including Nigeria, Liberia, Senegal, and others, this bloc favored a more gradualist approach, respecting national sovereignty and focusing on cooperation, not merger.

The Monrovia group won out. The OAU, founded in 1963, became a platform for coordination, not a supranational government. Its emphasis was on sovereignty, non-interference, and solidarity against colonialism, especially in Southern Africa.

Though Nkrumah was deeply disappointed, the OAU did help African nations support liberation struggles in Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. However, the dream of a politically unified Africa remained elusive.

Julius Nyerere and Philosophical Pan-Africanism

Another strong advocate of African unity was Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere, a leader of calm wisdom and socialist ideals.

Unlike Nkrumah, Nyerere preferred a bottom-up approach. He famously delayed Tanzania’s independence to allow a broader East African federation.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

In 1967, he helped form the East African Community (EAC) with Kenya and Uganda, hoping it would serve as a building block for continental unity. Although the EAC collapsed in 1977 due to political and ideological differences, it was later revived and expanded.

Nyerere often argued:

“Unity will not make us rich, but it can make it difficult for Africa to be disregarded and humiliated.”

Gaddafi’s Revival of the Dream

Fast forward to the early 2000s, and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya reignited the idea of a United States of Africa.

At numerous AU summits, he championed radical proposals:

A single African military to defend against Western interference.

A common African currency, the “Afro,” to challenge the dominance of the dollar and euro.

A continental passport and parliament.

Gaddafi even paid the AU membership dues of poorer African nations and funded pan-African media. In 2009, he became the Chairperson of the African Union and declared himself the “King of Kings of Africa. He invited hundreds of traditional rulers to Libya to swear allegiance to his vision.

However, many African leaders viewed Gaddafi’s ambitions as self-serving. Nigeria, South Africa, and Ethiopia—all regional heavyweights—remained skeptical. The 2011 NATO-led intervention in Libya, followed by Gaddafi’s death, ended his unification campaign.

African Union and the Realism of Integration

The African Union, established in 2002 as the successor to the OAU, represents a more pragmatic vision of Pan-Africanism. Rather than aiming for a single African nation, the AU focuses on deepening economic, diplomatic, and developmental cooperation among member states.

Its major achievements include:

African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA): Launched in 2021, it creates a $3.4 trillion market across 54 countries.

Agenda 2063: A strategic framework to transform Africa into a global powerhouse by 2063.

Silencing the Guns initiative: Aimed at ending all wars on the continent by reducing armed conflict and promoting stability.

It also established the Pan-African Parliament, though its powers are currently advisory rather than legislative.

Why Africa Didn’t Become One Country

Several deep-rooted challenges prevented full political unification:

Colonial Boundaries: The arbitrary borders drawn at the 1884-85 Berlin Conference ignored ethnic, linguistic, and cultural realities.

Ethnic and Linguistic Diversity: With over 1,500 languages and thousands of ethnic groups, cultural cohesion was difficult.

Ideological Differences: Post-independence governments ranged from socialist to capitalist to military juntas.

Fear of Hegemony: Smaller states worried about domination by powerful ones like Nigeria, Egypt, or South Africa.

Economic Disparities: Rich nations hesitated to share resources with poorer neighbors.

Foreign Interference: Former colonial powers and Cold War rivalries influenced and divided African leaders.

These factors made the dream of a single African state logistically and politically difficult.

Cultural and Economic Integration: The Silent Revolution

Despite the failure of full political unification, African countries are increasingly intertwined:

Afrobeats and Nollywood dominate continental entertainment markets and are now global phenomena.

Tech ecosystems in Lagos, Nairobi, and Kigali are driving digital innovation across borders.

Intra-African trade, though still low (about 17%), is growing with AfCFTA implementation.

African identity among youth is stronger than ever. Social media has created a pan-African consciousness where Gen Z and millennials identify more as “African” than their parents did.

A study by Afrobarometer in 2022 showed that nearly 63% of Africans under 30 support stronger continental integration.

Lessons from the European Union

Many Pan-Africanists looked to the European Union as a model. The EU began as a coal and steel community and evolved into a powerful bloc with a shared currency, parliament, and trade policy. Could Africa replicate this?

While the EU’s homogeneity and economic parity helped its integration, Africa’s diversity and underdevelopment make such a transition harder, but not impossible. Regional blocs like ECOWAS, EAC, and SADC are experimenting with open borders, shared currencies, and peacekeeping forces.

Conclusion: One Africa, Many Paths

Africa may not have become one country, but the dream of unity still pulses through its politics, culture, and economics. The vision of a “United States of Africa” is a reminder of what the continent could achieve when it thinks beyond borders.

In an era of globalization, climate crises, and shifting geopolitics, unity is not just symbolic—it is strategic. Africa’s collective future may depend not on becoming a single country, but on acting as one people.

Even if there is no single African president, no common passport (yet), and no continental anthem playing on loop, the idea of one Africa still inspires—and guides—leaders, artists, and citizens across the continent.

As Nkrumah warned, unity is not an option—it is survival. The dream hasn’t died. It has simply evolved.

More Articles from this Publisher

What’s Really in Your Pepper? FIIRO Warns of Toxic Grinding Machines

Heavy metals from common market grinding machines may be entering everyday meals, with FIIRO linking the exposure to ris...

High-Income Careers That Don’t Require Traditional University Paths

Some of the highest-paying careers don’t care where you studied. Skills, results, and execution now open doors that dipl...

Was Santa Claus Really Copied from African Masquerades?

Was Santa Claus copied from African masquerade traditions? The claim sounds bold, but the historical record tells a diff...

How Many Mudashiru Ayenis Have We Buried, Or Tagged As "Mad"?

He built a robot at 20. Instead of applause, Nigeria sent him to psychiatrists. This is the story of Mudashiru Ayeni, th...

7 Countries Where Valentine’s Day Isn’t February 14

Valentine’s Day isn’t always February 14. Some countries mark love on entirely different dates, and the traditions behin...

Countries That Have Restricted Valentine’s Day Celebration

Valentine’s Day is global but not universally accepted. In some countries, February 14 has been restricted, discouraged,...

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...