From Palace to Glass Case: The Colonial Theft of the Benin Bronzes

In February 1897, the British Empire carried out one of the most brutal acts of cultural destruction in African history. The once-thriving Kingdom of Benin, located in present-day Edo State, Nigeria, was invaded by British forces under the pretext of “punishment.” What followed was a massacre, the burning of the royal palace, and the looting of thousands of sacred artworks now known as the Benin Bronzes.

These masterpieces, cast in brass and bronze and carved in ivory, were not merely decorative objects; they were royal archives, spiritual relics, and vessels of collective memory. Their theft stripped Benin of its cultural soul and scattered its treasures across European and American museums. Today, the Benin Bronzes stand at the heart of debates on colonial injustice and restitution.

This is the story of how Britain stole a kingdom’s soul.

A Kingdom of Bronze and Brilliance: The Benin Empire Before the Invasion

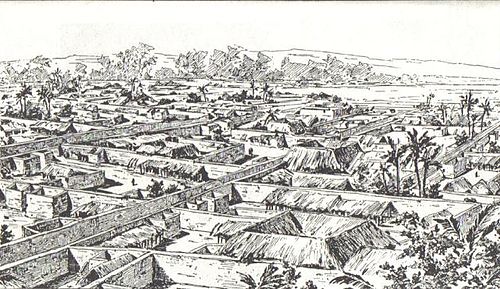

Long before colonial powers set their sights on West Africa, the Benin Kingdom was one of the most sophisticated states on the continent. Established around the 11th century, Benin flourished as a center of trade, art, and political organization. By the 15th and 16th centuries, it had become a dominant regional power, engaging in commerce with Portuguese traders who marveled at its urban planning and governance.

The Oba (king) of Benin was both a political ruler and a spiritual leader. His palace in Benin City was a sprawling complex, richly decorated with bronze plaques that chronicled dynastic history, significant battles, rituals, and the genealogy of the royal family. The walls of the city itself, stretching for over 16,000 kilometers in their entirety, were among the largest earthworks constructed before the mechanical age, larger even than the Great Wall of China when considered in total length.

READ ABOUT THE WALLS OF BENINHERE

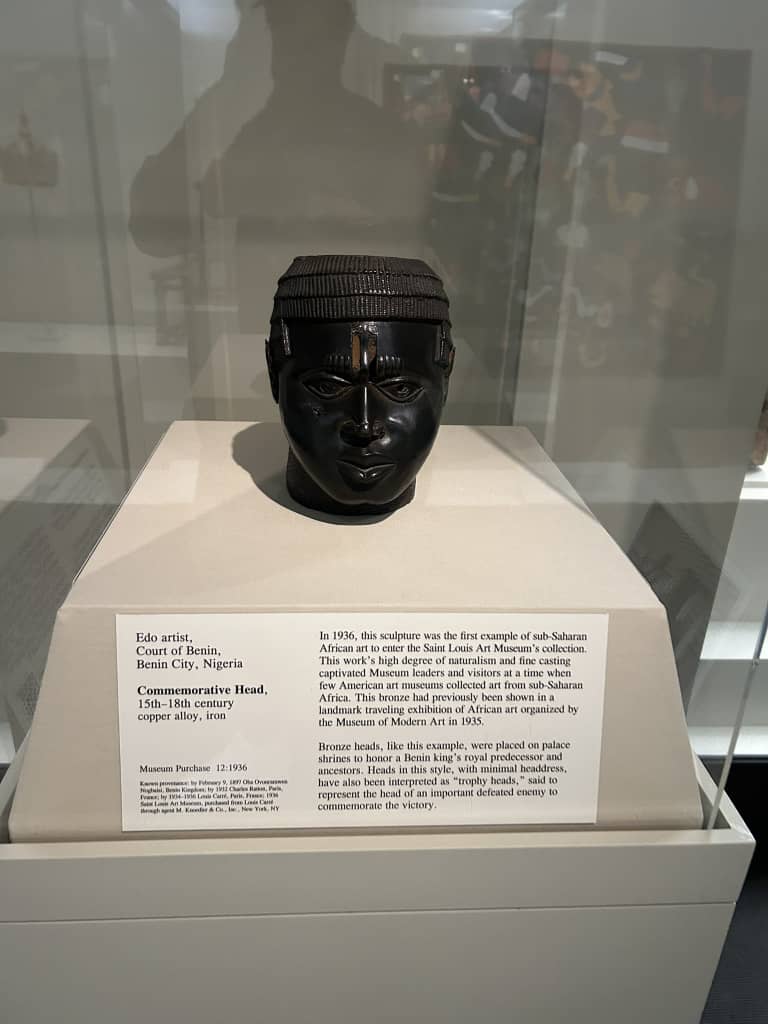

But it was Benin’s artistry that captured global attention. The so-called “Benin Bronzes”—a collective term for thousands of plaques, statues, and ceremonial objects made of brass, bronze, and ivory—were masterpieces of metalworking. They depicted scenes of court life, military power, and spiritual symbolism. These works were not merely aesthetic. They were historical archives, meticulously crafted to preserve collective memory and affirm the divine authority of the Oba.

The artistry of Benin was sustained by guilds, particularly the Igun Eronmwon (bronze casters’ guild), who served under royal patronage. Using the lost-wax casting method, they produced works of astonishing detail and durability. To Benin, these objects were not commodities—they were sacred, tied to the soul of the kingdom itself.

The 1897 Punitive Expedition: When Britain Brought Fire and Loot

The relationship between Benin and Britain began with trade in the 16th century. Over time, however, Britain’s appetite for control deepened. By the late 19th century, as European powers carved up Africa at the Berlin Conference (1884–1885), Britain sought total dominance over the Niger Delta’s lucrative palm oil trade. The Kingdom of Benin, under Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, resisted signing unfair trade treaties that would erode its sovereignty.

In January 1897, a British delegation led by Acting Consul General James Phillips attempted to enter Benin despite clear warnings from Benin chiefs that the Oba was engaged in sacred rituals and could not receive visitors.

The intrusion was seen as a provocation, and Benin warriors attacked the delegation, killing most of the party. Britain seized the opportunity, labeling the incident a “massacre” and launching a full-scale retaliatory campaign—the so-called Punitive Expedition.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

In February 1897, a British force of about 1,200 soldiers armed with Maxim guns marched on Benin City. What followed was a brutal invasion. The city was torched, thousands were killed, and the royal palace was reduced to ashes. Oba Ovonramwen was captured and later exiled to Calabar, where he died in 1914.

The destruction was accompanied by systematic looting. Soldiers stripped the palace of its treasures, over 4,000 bronzes, ivories, ceremonial masks, and royal regalia were seized. Many were taken as war booty by individual soldiers, while others were auctioned in London to cover the costs of the expedition.

What was framed by Britain as “punishment” was, in reality, an act of cultural plunder. The Punitive Expedition erased centuries of heritage in a matter of days, tearing the historical soul of Benin from its people.

Art as Identity: Why the Bronzes Were More Than Just Metal

To understand the magnitude of the theft, one must grasp the central role the Bronzes played in Benin’s cultural and spiritual life. These objects were not passive art pieces, they were living testaments to memory and power.

Each plaque or sculpture served as a royal archive, chronicling dynastic successions, military victories, and diplomatic encounters. Ivory tusks carved with intricate designs stood as symbols of continuity, while brass heads of former Obas were placed on royal altars to honour ancestors and sustain spiritual connections.

In Benin cosmology, bronze was imbued with spiritual power. It was believed to embody permanence and resilience, qualities linked to kingship itself. By casting the likeness of an Oba in bronze, the kingdom affirmed his eternal presence and divine legitimacy.

The looting of these artifacts was, therefore, more than material loss. It was cultural trauma. A people were stripped of their memory, their spiritual anchors, and their visual chronicles. The very objects that tied past to present were uprooted and shipped to foreign lands.

From Benin to British Museums: The Journey of Stolen Treasures

After the 1897 invasion, the stolen Bronzes began a long and fragmented journey. Many were auctioned in London to art dealers and collectors. The British Museum acquired over 200 pieces, making it the largest single holder of Benin Bronzes in the world. Others found their way to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the Berlin Ethnological Museum, and institutions across Europe and North America.

Photo Credit: Britannica | Palace plaques, brass relief sculptures by Edo artists in the court of the kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria), 15th–19th century; in the British Museum, London, which houses the largest collection of Benin Bronzes.

Today, more than 3,000 Benin Bronzes are scattered across the globe. Germany holds around 1,100 pieces, Britain about 900, while hundreds more reside in museums in the United States, France, and beyond. Only a fraction remain in Nigeria.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

The irony is stark: artifacts created to honour Benin’s kings are displayed in glass cases thousands of miles away, often with little acknowledgment of the violence that enabled their presence there. For decades, European museums justified holding these treasures under the guise of “preservation” and “universal heritage.” Yet, for the descendants of those whose ancestors crafted them, the absence of the Bronzes represents a wound that has never healed.

The Fight for Return: Decolonization, Restitution, and Justice

The call for the return of the Benin Bronzes began almost immediately after Nigeria’s independence in 1960. Successive Nigerian governments, scholars, and cultural advocates have pressed Britain and other nations to repatriate the artifacts.

For decades, these demands were met with resistance. Museums cited legal ownership, concerns over conservation, or the argument that the Bronzes had become part of “world heritage.” However, growing global awareness of colonial injustice has shifted the conversation.

In recent years, there has been tangible progress. In 2021, Germany announced it would return over 1,100 Bronzes to Nigeria. In the same year, The formal agreement established that ownership of the objects would be transferred back to Nigeria, following a 2021 memorandum of understanding, and that the return process would involve a roadmap developed over several months.

The first physical returns of these looted artifacts occurred in December 2022, with a portion of the bronzes being sent back to Nigeria to be housed in the new Edo Museum of West African Art.Jesus College, Cambridge, became the first UK institution to return a Benin Bronze, handing back a bronze cockerel.

The University of Aberdeen followed by returning a bronze head of an Oba. In 2022, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., returned 29 Bronzes to Nigeria.

Yet, the British Museum, holder of the largest collection, remains resistant. Bound by the British Museum Act of 1963, the institution claims it cannot legally deaccession its collection. Critics argue this is a convenient shield to avoid confronting the moral imperative of restitution.

Meanwhile, Nigeria has been preparing to house its returning treasures. Plans are underway for the Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA) in Benin City, designed by architect David Adjaye, which aims to become a world-class facility for showcasing the Bronzes in their cultural context.

The fight for restitution is not only about returning objects but about restoring dignity, memory, and history to a people denied their heritage for over a century.

Conclusion

The story of the Benin Bronzes is a story of beauty, violence, and resilience. It is the story of a kingdom whose artistry was unparalleled, whose sovereignty was violated, and whose treasures were scattered across the globe. The British Punitive Expedition of 1897 was not just a military campaign, it was an act of cultural theft that robbed a people of their soul.

Yet, the Bronzes endure. Their brilliance continues to dazzle museumgoers worldwide, but their true power lies in their origin. They belong to Benin, to Nigeria, to Africa. The global restitution movement is about more than art, it is about justice, healing, and reclaiming identity.

As nations reckon with the legacies of colonialism, the question remains: how long will the soul of Benin remain divided across foreign museums? The answer will define not only the future of the Bronzes but also the moral conscience of the modern world.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...