The Science of Why We Procrastinate

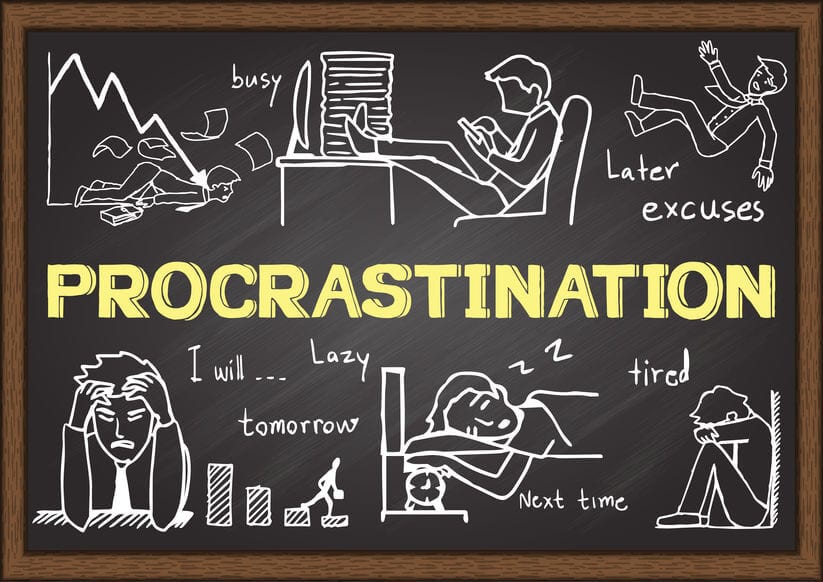

We’ve all sat down to work on something important, only to find ourselves scrolling through social media, checking emails, or staring blankly at the wall. It’s frustrating, sometimes embarrassing, and often leaves us wondering: Why do I keep putting things off? The answer is not simple, procrastination is a complex mix of brain wiring, emotional patterns, and environmental factors. Understanding the science behind it can turn this common struggle into an opportunity for greater focus, productivity, and even self‑compassion.

Why Our Brains Often Choose Delay

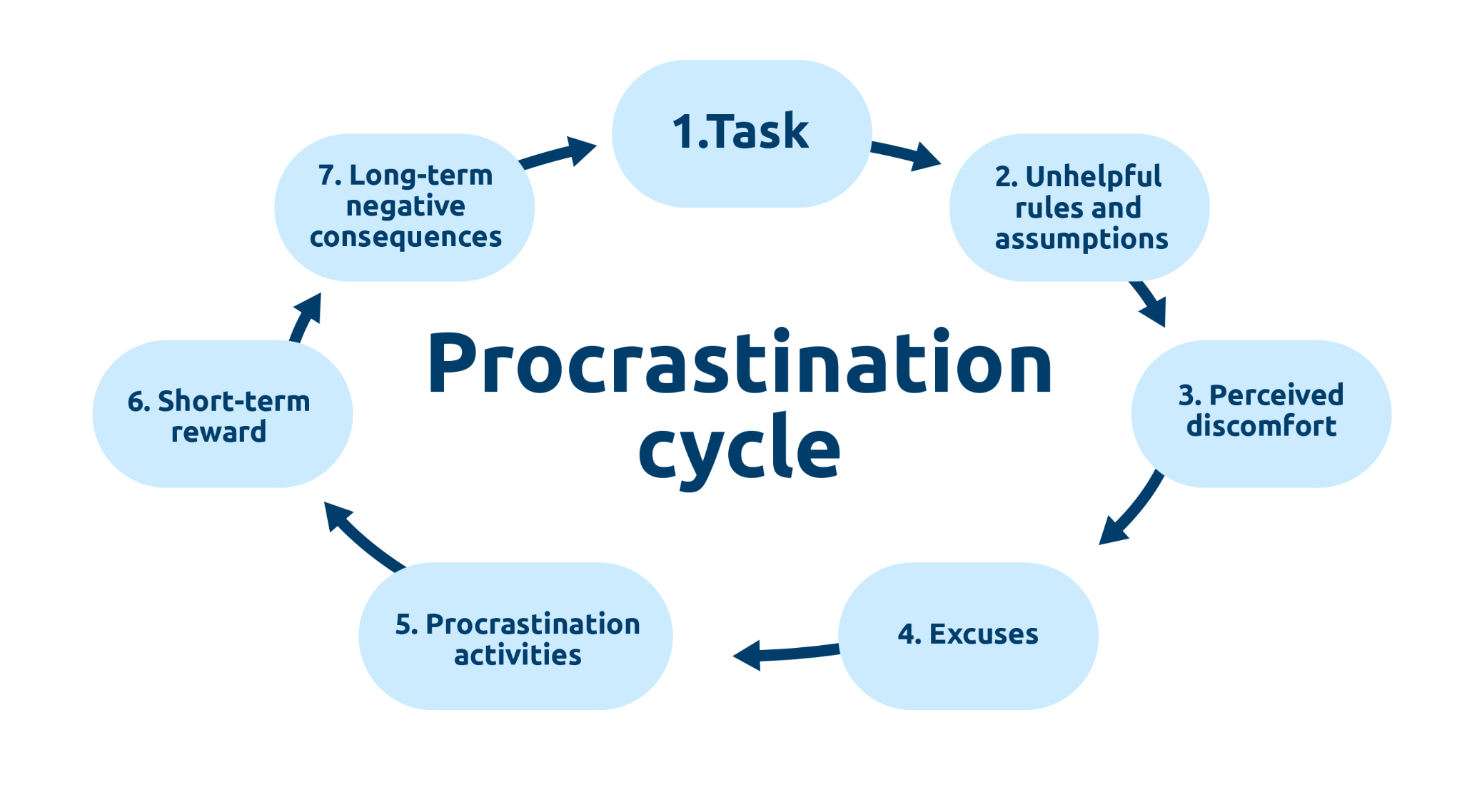

Procrastination is rarely about laziness. It originates in how the brain balances discomfort and reward. When a task feels overwhelming, boring, or emotionally taxing, the mind favors immediate relief over long‑term goals. According to a release by the American Psychological Association on stress and procrastination, delaying a task is often a form of emotion regulation, a way for the brain to reduce stress in the moment, even if it creates problems later.

Repeated avoidance reinforces neural pathways that make procrastination habitual. Every time a person chooses distraction over action, the brain learns to associate difficult tasks with anxiety. Over time, the pattern hardens into a default response, making even motivated individuals prone to delay despite their best intentions. Understanding this neurological dynamic explains why procrastination is so common and so persistent.

Emotion, Mood, and Hidden Triggers

Procrastination is deeply linked to emotions, particularly fear of failure and perfectionism. People often delay tasks to avoid confronting uncomfortable feelings, such as self-doubt or potential criticism. This avoidance offers temporary relief but magnifies stress as deadlines approach.

Mood and energy levels play a critical role as well. When tired, overwhelmed, or anxious, even simple tasks can feel insurmountable. Instant gratifications, scrolling social media, watching videos, trigger dopamine release and reward the brain for avoidance. Over time, this creates a cycle where procrastination becomes a natural response to stress, anxiety, or low motivation.

The Role of Habit and Environment

Procrastination often becomes a habit, reinforced by repetition and reward. Behavioral science describes a habit loop: cue, routine, reward. A stressful assignment acts as a cue, delaying the task becomes the routine, and relief from stress is the reward. This loop strengthens over time, making procrastination the brain’s default reaction.

Modern environments exacerbate the problem. Smartphones, streaming platforms, and constant notifications provide endless distractions, making immediate rewards from avoidance too tempting. Additionally, unclear goals, chaotic workspaces, and poorly structured routines make focus difficult, weakening the prefrontal cortex’s ability to plan and prioritise. By shaping both habits and surroundings, procrastination persists as a default behavior until intentional change is applied.

Consequences of Chronic Procrastination

The effects of procrastination extend beyond missed deadlines. Chronic delay contributes to stress, anxiety, and diminished mental health. A peer‑reviewed study published in Personality and Individual Differences found that habitual procrastinators report significantly higher levels of stress and lower life satisfaction compared to non‑procrastinators. Procrastination can impair professional performance, damage relationships, and erode self‑esteem. People trapped in cycles of avoidance often feel guilty or helpless, reinforcing negative self-perceptions. Recognizing procrastination as a complex interaction of brain function, emotion, and environment helps shift the approach from self-blame to practical solutions.

Strategies to Overcome Procrastination

Understanding the science allows for actionable strategies. Time‑blocking is one proven method, where individuals allocate dedicated periods for work, breaks, and leisure. Structured schedules reduce decision fatigue and improve focus.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

The “two‑minute rule,” popularized by productivity expert David Allen, encourages starting tasks that take less than two minutes immediately. This helps overcome initial inertia and builds momentum, making larger tasks feel more manageable. Adjusting the environment also matters: reducing distractions, organizing workspaces, and creating boundaries signals the brain that focus is expected.

Mindset shifts are critical as well. Framing tasks as opportunities for growth, rather than chores, reduces emotional resistance. By pairing action with reward and celebrating small wins, the brain associates progress with satisfaction rather than stress. Collectively, these strategies reshape habits, counter emotional triggers, and reinforce productive behaviors.

Why Understanding Procrastination Matters Today

In a world full of constant stimuli, procrastination is more than a personal challenge, it is a societal phenomenon. For students, professionals, and creatives, understanding the causes of procrastination can improve productivity, reduce stress, and enhance life satisfaction.

By recognizing procrastination as a result of brain wiring, emotion, and environment rather than laziness, individuals can approach it with compassion and strategy. Breaking the cycle requires intentional action, environmental adjustment, and emotional awareness.

When procrastination is understood and addressed, what once was delay can transform into momentum. Recognizing the science behind it is the first step toward reclaiming focus, achieving goals, and fostering personal growth.

Procrastination is rooted in human brain function, emotion, and habit, not character flaws. It arises from the brain’s preference for short‑term relief over long‑term gain, reinforced by repeated avoidance and environmental distractions. By implementing strategies like time‑blocking, small actionable steps, and positive environmental adjustments, procrastination can be mitigated. Understanding its scientific basis transforms delay from a destructive habit into a manageable challenge, empowering individuals to reclaim productivity, confidence, and personal growth.

You may also like...

Shock Doping Suspension: Chelsea Star Mudryk Spotted Training at Non-League Club

Chelsea winger Mykhailo Mudryk is training at non-league club Uxbridge FC amidst his provisional suspension for a doping...

World Cup Chaos: Super Eagles vs Team Melli Clash Faces Roadblock Amid Iran Doubts

A friendly football match between Nigeria's Super Eagles and Iran faces uncertainty due to an escalating crisis in Iran,...

Half-Century Celebration: Hong Kong Film Festival Honors Legends!

The Hong Kong International Film Festival marks its 50th anniversary with a retrospective celebrating Chinese-language c...

Director's Fiery Condemnation: Rasoulof Labels Khamenei 'Most Hated Figure'!

Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof has strongly condemned the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was r...

Innovative Fusion: French Artist Blends Greek and Rwandan Traditions

French artist and architect Guillaume Sardin, based in Paris, integrates Rwandan history and visual culture into his art...

Zimbabwe's Top Artists Honored: Full NAMA Awards Winners Revealed!

The National Arts Merit Awards (NAMA) celebrated "Fearless Creativity" at a glittering ceremony, honoring top Zimbabwean...

Max Minghella Decodes Iconic Rivalry: 'Industry' Star Connects Batman-Joker to Whitney's Downfall!

Max Minghella delves into his role as the enigmatic Whitney Halberstram in "Industry" Season 4, detailing the character'...

HGTV Stars Spill Secrets: D'Arcy Carden and Sherry Cola Unveil Wildest Vacation Spot on New Show!

HGTV's "Wild Vacation Rentals" features comedians D'Arcy Carden and Sherry Cola touring America's most outrageous rentab...