The Forgotten Flu: How the 1918 Pandemic Reshaped Global Health

Introduction

On the cold morning of March in 1918, in the rural expanses of Haskell County, Kansas, a single man, a U.S. Army cook named Albert Gitchell, slipped into an infirmary, complaining of fever, sore throat, and chills. In weeks, more than 100 soldiers had joined him, ill with what was then called “a severe influenza.” That seemingly ordinary outbreak would swell into history’s deadliest pandemic, the fabled Spanish Flu.

Over the next two years, the virus would sweep every inhabited continent; infecting roughly one-third of the world’s population and killing tens of millions in its wake. Yet today, a century later, its lessons are often forgotten, overshadowed by wars, politics, and modern pandemics. This is the story of how the 1918 flu destroyed lives, upended public health, and carved a new epoch in global medicine.

The Ghost in the Trenches: Origins and Early Spread

The 1918 influenza pandemic is one of epidemiology’s enduring mysteries. While commonly called the “Spanish Flu,” evidence suggests the virus did not originate in Spain. The earliest credible cases trace back to Haskell County, Kansas, in January–March 1918.

From Kansas, the virus silently traveled with soldiers mobilizing for World War I. Conditions in military camps, crowded quarters, poor sanitation, movements across continents, created perfect conditions for viral spread.

By April and May 1918, outbreaks appeared in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Simultaneously, ships docking at ports, troops disembarking in Europe, and human traffic in wartime zones carried the pathogen far beyond its origin.

The war’s censorship masked the growing terror. Spain, neutral in WWI, freely published influenza reports, giving the misleading impression that the disease was centered there — thus “Spanish flu.”

The pandemic unfolded in distinct waves. The first wave in spring 1918, though widespread, was relatively mild. The second wave, beginning in autumn 1918, brought devastation of an order unseen before. A third wave in early 1919 followed in some regions.

The Human Cost: Death, Suffering, and the Age Paradox

By century’s end, estimates place the death toll between 50 million and 100 million, more than World War I itself. Conservatively, historians often cite 50 million.The virus infected about 500 million people, roughly one-third of Earth’s then population.But death was not uniform. The pandemic displayed a grim anomaly: unusually high mortality among young adults (ages 20–40), a departure from typical influenza, which most heavily kills the very young and the elderly.

Why did that cohort perish so disproportionately? One hypothesis involves the so-called “cytokine storm,” wherein immune systems of the healthy overreacted, causing self-inflicted lung damage.

Much of the fatality came not directly from influenza, but secondary bacterial pneumonia, opportunistic infections running rampant in compromised lungs. In many fatal cases, the lungs filled with fluid, hemorrhaged, and collapsed.

In the U.S., an estimated 675,000 Americans died. The outbreak reduced life expectancy by about 12 years in 1918 alone. Cities saw over 25 % of their populations fall ill. In Philadelphia, one infamous event, the Liberty Loans Parade on September 28, 1918 — drew over 200,000 people, precipitating a massive local outbreak. Over 12,000 died in Philadelphia alone.

Many remote regions were not spared. Island nations, Arctic communities, the tropics, the flu found everyone as it ravaged the earth at that time.

In India, then under British rule, the toll was particularly catastrophic. Scholars estimate 10–20 million died, the highest count of any single nation. One study placed the number at 13.9 million in British Indian districts. The pandemic coincided with famine, monsoon failure, mass migration, and upoor nutrition, exacerbating mortality.

Public Health Strikes Back: Trials, Measures, and Failures

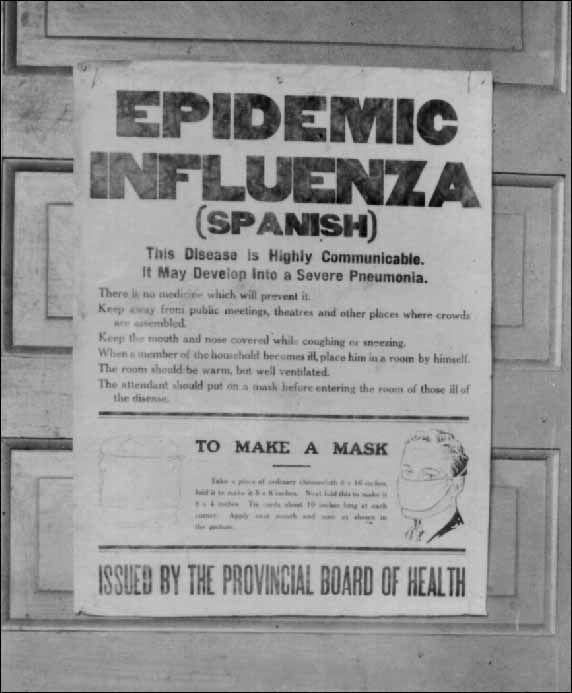

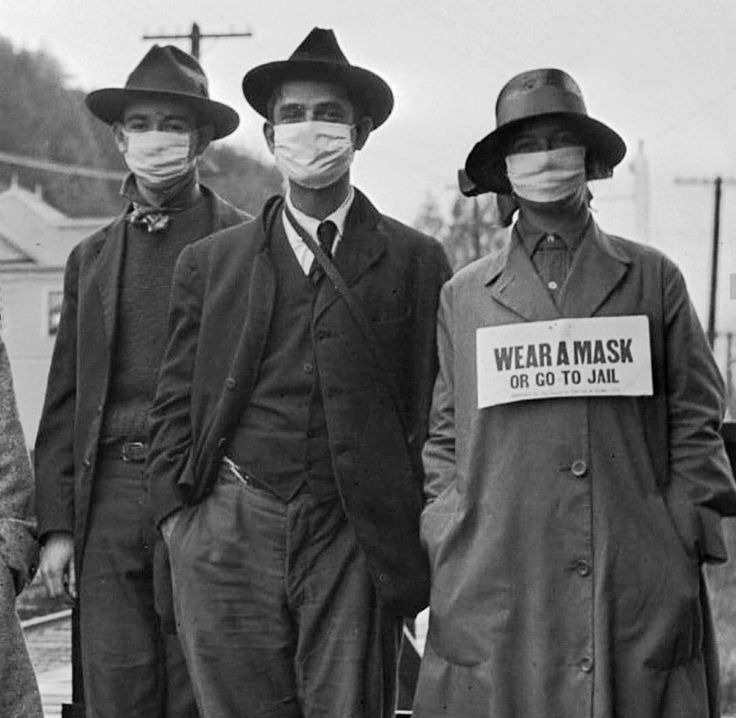

In 1918, modern epidemiology was in its infancy. Public health systems were weak; antibiotics did not yet exist; vaccines were undeveloped. Responses were ad hoc, local, and often inconsistent.Cities scrambled to apply known disease control tools: quarantine, isolation, school and theater closures, banning public gatherings, mask mandates, and sanitation efforts.

St. Louis, famed for early and strict intervention, managed to flatten its curve better than Philadelphia, which delayed action. In Philadelphia, the Liberty Parade is retrospectively condemned as a tragedy in public health mismanagement.In San Francisco, the public backlash led to the formation of the Anti-Mask League, protesting mandatory mask ordinances. The requirements were repealed, reinstated, and repealed again as cases waxed and waned.

In many places, lines of bodies stacked in morgues, funeral services overwhelmed, and mass graves appeared. Health systems collapsed under burden.Analyses of U.S. cities show that fast, stringent non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) reduced peak mortality by about 50% and cumulative excess deaths by 24–34%.Importantly, these interventions did not worsen medium-term economic outcomes, suggesting that health and economy might not always be at war.Yet enforcement was uneven, compliance variable, and public fatigue common. Even in 1918, information, rumors, and resistance hampered compliance.

Science Rises From Ashes: Understanding the Virus

In the decades that followed, the 1918 influenza virus was partially reconstructed through techniques using preserved tissue samples from victims, including from bodies buried in Alaskan permafrost. These studies offered insights into viral evolution, virulence, and host interaction.Sequencing revealed that the 1918 virus was an Influenza A (H1N1) strain with genes likely of avian origin, but adapted to humans.Researchers have identified singular mutations in its hemagglutinin (HA) gene e.g. a rare glycine at position 188, that may have contributed to its binding and virulence characteristics.

Still, mysteries remain: the exact origin, the precise drivers of its high mortality, and why immunity in survivors varied.Molecular reconstructions allowed experimental infections in labs (high biosafety containment). These helped show how deep lung infection, cytokine storm, and viral adaptation might interact.

From that work, epidemiologists built models to understand how war logistics, troop movement, and civilian travel amplified spread confirming that WWI amplified the pandemic’s reach.

Global Shifts: How the 1918 Flu Reshaped Health Systems

Before 1918, global health was largely reactive and poorly coordinated. The pandemic exposed yawning gaps and propelled innovations in public health infrastructure.

Rise of National Health Agencies & Surveillance

Countries realized that systematic disease surveillance, data sharing, and coordinated crisis response were no longer optional. Many nations created or expanded centralized public health agencies, investing in epidemiology, virology, and diagnostic labs.

International Cooperation & the League of Nations Health Mandate

In the 1920s, the League of Nations established its Health Organization, a precursor to the WHO. Influenza and pandemic preparedness became part of its early mandate. The idea: disease knows no borders.

Vaccine Research & Virology as Disciplines

Though a flu vaccine for the 1918 strain was not available then, the pandemic accelerated interest in influenza virology, immunology, and vaccine research. Scientists began cataloging viral strains, cross-immunity, and antigenic drift.

Social and Economic Policy Integration

The economic and social toll forced integration of public health with social welfare policy. Governments more seriously considered how poverty, nutrition, housing, labor, war, and hygiene affect disease transmission.

Preparedness Mindset

The concept of a “pandemic era” took root: the world no longer viewed influenza as seasonal only, experts recognized that occasional global outbreaks would recur. By mid-20th century, influenza became a model system for understanding viral pandemics, surveillance networks, vaccine strain selection, and global cooperation.

Legacies, Lessons, and Warnings

Trust, Communication, and Misinformation

In 1918, inconsistent messaging, censorship, and variable compliance eroded public trust. Some communities refused to heed health orders, masked in denial and rumor. The tensions between civil liberties and public health measures echo today.

The Danger of Complacency

A century on, decades pass without a pandemic of comparable scale, lulling many into a false sense of security. But influenza viruses continue evolving; zoonotic spillovers remain an ever-present threat.

Infrastructure Must Be Sustained

Preparedness cannot be episodic. Maintaining public health labs, surveillance systems, stockpiles, and capacity in peacetime is vital — as later outbreaks (e.g. 1957, 1968, H5N1) have reminded us.

Global Equity & Access

The 1918 flu disproportionately impacted undernourished, overcrowded, impoverished populations, stressing that pandemics are also social diseases. Health equity must be baked into responses.

Science humility

Even now, a pathogen of similar ferocity could surprise us. The 1918 virus taught that viruses evolve, immunity wanes, and perfect prediction is illusory.

Epilogue: A Forgotten Cataclysm

Today, few outside medical historians remember the details of the 1918 pandemic. Its centennial in 2018 brought renewed interest, but its stories remain absent from many public narratives. Yet in laboratories, viral archives, and global health offices, the ghost of 1918 still haunts decisions. Vaccines, pandemic planning, surveillance systems, these trace their lineage to that catastrophe.

The world that emerged from 1918 was irreversibly changed. The notion of global health, pandemics, and epidemiology was recalibrated. Next time a novel pathogen emerges, we may lean on the memory of that forgotten flu or repeat the mistakes all over again and this might just be a call for the African continent to invest in its health sector and put infrastructure in place to ensure the safety of her people.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...