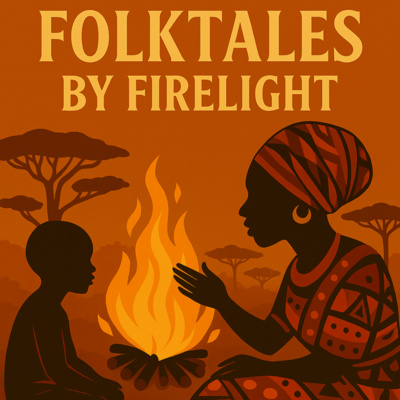

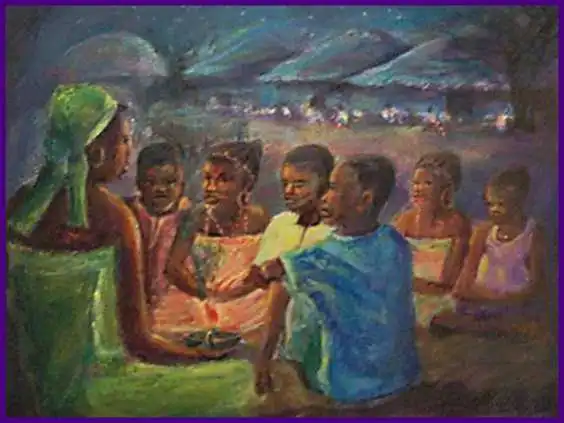

Remembering the Nights We sat by the Firelight, Listening to Moonlight Stories

There was a time when the night spoke softly, when voices rose with the hum of crickets, and stories drifted through the warm air like the smoke of the fire. Children gathered close, eyes wide, hearts open, waiting for the familiar rhythm that began every tale: “Once upon a time…”

In those days, nightfall wasn’t the end of activity, it was the beginning of community. When the sun dipped below the horizon and the sky darkened into deep blue, families drew closer. The old sat on low stools, children formed small circles, and the firelight flickered across eager faces.

The night was filled with the smell of burning wood, the chirp of crickets, and the rhythmic voice of an elder ready to speak. The tales told weren’t random, they were reflections of who we were. They spoke of loyalty, courage, greed, patience, and the spirit of community.

Across Africa, from the Igbo and Yoruba to the Ashanti, Akan, Zulu, and Shona, the practice of telling stories by moonlight was both education and entertainment. These evenings were more than leisure, they were the heartbeat of oral tradition. According to a study on African folktales and cultural transmission by the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, storytelling by firelight “served as an informal classroom where moral instruction, social values, and language were passed from one generation to another.”

The Meaning of “Moonlight Stories”

The phrase moonlight stories or tales by moonlight, as popularised in Nigeria describes a tradition where elders narrated folktales to children under the gentle watch of the moon. It was a performance. The storyteller’s hands moved; voices changed with each character; songs broke the rhythm; riddles invited laughter.

Each story carried a lesson. There was “The Tortoise and the Birds,” “Why the Sky Is Far Away,” “The Lion’s Greed,” and countless others. Every character symbolised a moral truth and every child learned without feeling lectured.

Among the Yoruba, the storyteller was often the Alárinàkò, a custodian of community knowledge. Among the Igbo, the Akụkọ Nne (mother’s tale) reflected wisdom passed through maternal lineage. It was how children learned respect for elders, compassion for others, and the consequences of disobedience. These were the earliest classrooms, long before schools and blackboards.

In modern times, we stare at screens; in those days, we stared at flames. The firelight was the original theatre, projecting flickers of orange that made every story come alive. When the elder spoke of a lion, shadows on the wall seemed to move; when a trickster spoke, faces lit up with mischief.

The power of those nights lay in their slowness. There was no rush, no interruptions, no scrolling. Each story built anticipation; each pause drew the children closer. A 2021 anthropological study on the San people of Southern Africa described firelight storytelling as “a sacred exchange of energy when work stops, and imagination takes over.”

The firelight gatherings were also spaces for laughter and bonding. Adults joined in, correcting or teasing the storyteller. After each story, came songs and drumming. There was rhythm in the silence, connection in the pause, and learning in the laughter.

While these stories varied across tribes and tongues, their purpose remained the same; to teach and preserve.

“Why the Tortoise Has a Cracked Shell” taught humility and honesty.

“The Greedy Hyena” warned against selfishness “The Clever Hare” celebrated wit and wisdom.

These tales were structured around moral values and communal ethics. They were not abstract myths; they were social tools. As noted in the International Journal of Culture and History, moonlight storytelling “promoted moral discipline, collective responsibility, and respect for societal order.”

For many, these were the first leadership lessons, learning how to listen, when to speak, and why every action had consequence. It was a training ground for empathy and moral intelligence long before the phrase emotional intelligence existed.

The Disappearing Circle

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Then came modernity. First, electricity and radio, then television, and later, smartphones. The moonlight was dimmed by fluorescent bulbs, and the firelight gave way to blue screens. Children no longer sat in circles, they sat apart, eyes fixed on their own glowing rectangles.

The communal story hour faded. The few who tried to preserve it found that attention spans were shrinking. The sacred silence of listening was replaced by the quick thrill of watching.

Cultural historians have described this shift as a loss of social glue. Storytelling once kept families together, reinforced identity, and ensured continuity. Now, the storyteller’s role has been reduced or replaced by television anchors and content creators.

But something essential was lost in translation: the warmth of human presence. The storyteller’s eyes, the tone of the voice, the crackle of the fire, these cannot be replaced by pixels or playlists.

Yet, even in this modern landscape, traces of the firelight still exist. The art of storytelling has simply migrated. African creators now use podcasts, YouTube storytelling channels, and documentaries to revive oral traditions.

In Nigeria, shows like Tales by Moonlight first aired on Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) in the 1980s, have found new life online, introducing a new generation to old tales. On Spotify, storytellers like Omasan Fenemigho keep folklore alive through modern formats.

In schools, cultural clubs reintroduce storytelling nights, encouraging children to tell their grandparents’ tales in their own words. The Nigerian Cultural Preservation Project has also started community initiatives to record oral histories before they vanish.

It’s easy to dismiss these old tales as relics but they hold the essence of our worldview. Every proverb, every character, every fable is a thread in the fabric of African identity. Without them, history becomes hollow.

The moonlight stories taught resilience, faith, and humour, tools that helped our parents survive uncertainty. In a time when society is fragmented by individualism and technology, returning to that collective rhythm might just be what we need to restore balance.

As one Ghanaian educator put it in a 2023 symposium on African indigenous knowledge, “Our stories were our first form of therapy. We laughed through hardship. We learned to forgive through tales. We found hope through fables.”

Keeping the Flame Alive

Today, a new generation of storytellers from filmmakers to podcasters are finding ways to blend firelight and fibre-optic cables. The essence remains the same: to gather, listen, and feel.

In some villages, the old tradition still breathes. On cool nights, elders still call the children to sit by the fire, and voices still rise with laughter and song. It might not be every night anymore, but it survives and that survival is victory enough.

What we need now are deliberate efforts:

Schools can integrate local storytelling into creative arts classes.

Parents can dedicate “story nights” at home without gadgets.

Cultural organisations can sponsor moonlight storytelling festivals, blending heritage and innovation.

The goal is not to romanticise the past but to recognise its living value. Storytelling isn’t dead, it’s waiting to be rekindled.

The nights we sat by the firelight weren’t just childhood memories; they were lessons in patience, empathy, and belonging. The fire wasn’t only for warmth, it was a mirror of our shared humanity.

Today’s world may be brighter, but in many ways, it’s colder. Perhaps that’s why we keep looking back at those glowing nights, when laughter echoed into the trees and stories travelled farther than any signal ever could.

The firelight may have dimmed, but its glow remains in every African heart that still in the power of a story well told.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...