Nigeria’s Dangerous Culture of Turning Trauma Into Entertainment

INTRODUCTION: A Country Numbing Itself With Humour

Nigerians are the happiest set of humans; the way we find laughter in the midst of chaos should be studied.

But no; what should really be studied is how quickly we turn trauma into entertainment before we even finish counting the bodies or process what’s actually going on.

For years, the world has marvelled at the Nigerian ability to smile through suffering, to spin tragedy into jokes, to light up timelines with humour even as the ground beneath us burns. We’ve been praised and acknowledge at h ow we still find happiness in the midst of chaos.

It is a coping mechanism that has become part of our national identity, a psychological armour forged from decades of instability, corruption, and hardship. But in recent times, that armour has cracked into something darker: indifference disguised as humour, entertainment mined from the pain of others, and a digital culture that trivialises horror faster than it reports it.

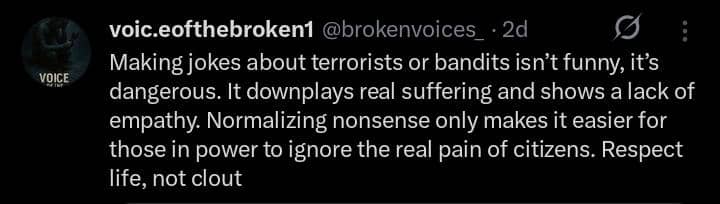

The recent spike in bandit attacks across the country should have forced a national reckoning. Instead, it inspired a wave of comedy skits, TikTok content, and meme templates. While families are in forests negotiating ransom, while communities are burying their dead, while survivors are still trembling through the shock, content creators are staging mock kidnappings with toy guns and dramatic screams, all for likes, comments, and ad revenue.

This isn’t the “resilience” Nigerians love to romanticise. This is collective emotional burnout dressed as banter. We don’t process trauma in Nigeria, we package it.

And the packaging is always the same: jokes, memes, “omo life hard o” punchlines, and now, the peak of collective madness; direct engagement with the very criminals killing and kidnapping fellow citizens. Not out of courage. Not out of confrontation. Out of boredom and a desperate need to feel something other than fear.

A Violence Industry Masquerading As ‘Content’

The Nigerian laughter culture didn’t begin today. It’s been reinforced by decades of jokes about fuel scarcity, inflation, NEPA outages, and corruption scandals. According to them, it’s dark humour and “It’s not that deep”

It became our survival language, a way to tell ourselves that the chaos was manageable, that we still had control.

But the myth has hardened into something more dangerous: the belief that humour is the only acceptable emotional response. Anything else — outrage, grief, protest, vulnerability — is treated as overreaction.

So Nigerians learned to laugh. Relentlessly. Compulsively. Even when it made no sense.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

The danger is that laughter, when overused, stops being a coping mechanism and becomes a reflex, one that flattens tragedy into spectacle.

When Tragedy Became Content

The shift didn’t happen overnight. It crept in gradually as social media rewired our instincts. Every event, no matter how catastrophic, became an opportunity for visibility. A chance to trend. A shot at virality.

So when banditry escalated from rural menace to national emergency, the online ecosystem did what it always does: turned it into a genre.

Within hours of reported attacks, skits began circulating. Creators staged fake ambushes. Actors in camouflage uniforms exaggerated the accents of northern communities. Some pretended to negotiate ransom over WhatsApp. Others dangled plastic rifles and shouted “everybody down!” with comedic flair.

But behind every punchline are families who don’t know whether their loved ones are dead or alive. Behind every viral video is a child who now sleeps with the memory of gunshots ringing through their head. Behind every skit is a community still sweeping blood from the streets.

Humour stops being harmless when it buries human suffering under punchlines.

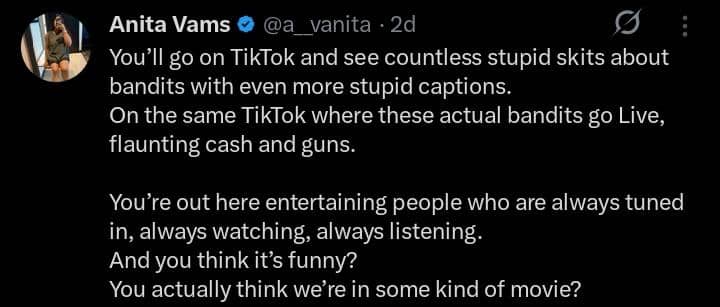

The TikTok Problem: When Bandits Go Live and Citizens Engage

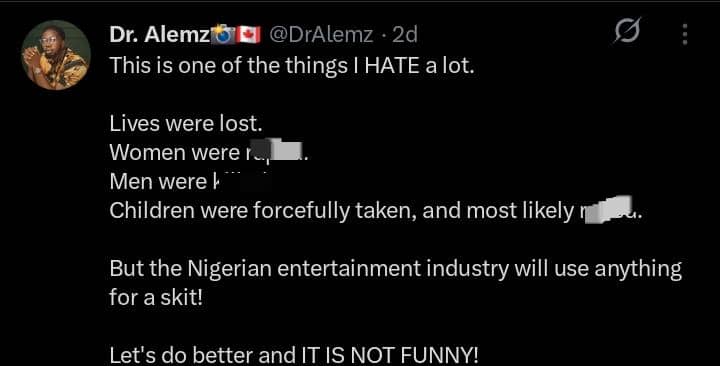

Then came something even more disturbing: Nigerians joining TikTok livestreams hosted by actual bandits.

The same people kidnapping villagers, raiding communities, and terrorising highways have found an audience, not in shadows, but on mainstream platforms. And Nigerians joined the livestreams, typed comments, laughed, asked questions, sometimes even hailed them. Engagement metrics rose. Views skyrocketed.

Think about what that means.

We are interacting with the very people destroying lives, treating them like internet personalities instead of criminals. The line between perpetrator and performer has blurred. The violence becomes content, and content becomes entertainment.

This isn’t just apathy. This is moral decay accelerated by algorithm.

TikTok does not care whether a livestream is hosted by a dancer or a bandit. The platform rewards engagement, not ethics. And Nigerians, conditioned by years of “laugh through pain”, showed up, typed “lol,” and kept the momentum going.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

When bandits realise they can gain attention, validation, and even followers, the terror takes a new shape. Violence becomes branding. Atrocity becomes PR. And the public becomes complicit.

When you keep watching something as entertainment, you subconsciously soften your moral posture towards it.

The way Nigerians now treat bandits is dangerously close to the way Americans treat serial killers in documentaries as “interesting” characters instead of violent criminals.

This has consequences:

1. You reduce the seriousness of the crime.

2. You create social familiarity with evil.

3. You blur the emotional boundary between the victim and the audience.

4. You unintentionally encourage criminals who now see fear as a currency.

If a bandit knows that going live on TikTok will gather an audience of thousands of Nigerians laughing, engaging, and playing along, what incentive does he have to stop?

You’ve turned his violence into virality.

You’ve given him reach.

You’ve given him applause; even if it’s ironic.

Criminals are not philosophers.

They don't care about nuance.

They see engagement as power.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Don’t get it wrong: comedy and skits are not inherently harmful. They have long served an educative and mobilizing purpose, showing that humour can illuminate injustice rather than numb it.

The difference between #EndSARS skits and the recent bandit-content trend is stark. During the protests, comedians and content creators used humour as a tool for resistance, not escapism. Mr Macaroni’s skits, for instance, dramatized police brutality and called out injustice, turning laughter into a rallying cry rather than a distraction.

The humour amplified victims’ voices, educated audiences, and pressured authorities to respond. It was purposeful, morally grounded, and anchored in empathy. Contrast this with the viral bandit livestreams and staged ambush skits, where laughter masks fear, desensitizes viewers, and blurs the line between tragedy and entertainment. Context, intention, and ethical framing are what separate humour that heals from humour that numbs.

Laughter As Form Of Escapism

The real problem isn’t that Nigerians laugh. It’s that laughter has become our default setting, even when the situation demands outrage, empathy, or collective action.

We’ve overstretched the coping mechanism until it snapped.

We retweet jokes about death but skip the donation links.

We laugh at skits but avoid reading survivor testimonies.

We debate comedy while corpses are still warm.

It’s no longer about resilience. It’s about avoidance.

Avoiding the weight of reality.

Avoiding the helplessness that comes with confronting a broken system.

Avoiding the guilt of knowing we are part of a society that has normalised fear.

Humour gives us escape; but it also erodes our sensitivity. Over time, repeated exposure to violence framed as content desensitises us. Psychologists call it compassion fatigue. When tragedy becomes too frequent, the human brain shuts down its emotional response to protect itself.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

That’s where Nigeria is now: emotionally exhausted, socially numb, and mentally withdrawing. And content creators have become accelerators of that numbness.

The Cost: A Nation Losing Its Emotional Intelligence

Behind every joke, there is someone who is not laughing. But we rarely pause long enough to consider them.

A woman whose husband was taken from their car and dragged into the bush.

A child who still wakes up screaming.

A community that has lost its farmers and cannot feed itself.

A mother waiting for a ransom call that may never come.

A student who was kidnapped on her way home and returned with eyes that will never be the same.

These people do not care about “cruise.”

They do not understand why their trauma has become trending content.

They do not know why the nation laughs while their lives crumble.

When a society begins to mock what it should mourn, something fundamental has broken.

Who Is Responsible? More People Than We Like to Admit

It’s easy to blame content creators. But the truth is uglier: they create because there is demand.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

We watch the skits, share the memes, inflate the engagement and, encourage the next joke.

The creator with a conscience will think twice. The creator chasing reach will not. And social media algorithms reward those who move fastest, not those who move ethically.

The government also plays a role; its silence, inefficiency, and detachment create a vacuum that content fills. When people lose faith in leadership, they retreat into entertainment because the alternative is despair.

But we, the citizens, also have blood on our hands, not literally, but morally. Through laughter, through apathy, through indulgence, we contribute to the normalization of violence.

A Country That Needs to Feel Again

Nigeria doesn’t need to stop laughing. Laughter has saved us in ways we cannot quantify. But we need to reclaim the boundary between humour and harm. We need to remember how to be human in the face of other people’s pain.

We have to unlearn the instinct to joke about everything, especially tragedies that demand seriousness. We have to recognise that empathy is not weakness. That outrage is not unnecessary drama. That silence can be more respectful than punchlines.

To feel again is to reclaim our humanity.

What kind of country laughs while watching its own wounds bleed?

Not a happy country, and definitely not a resilient one; but maybe a numb one.

And numbness, if left untreated, becomes a graveyard of empathy.

Until Nigeria starts feeling again, until we stop turning tragedy into trend, we will continue to lose far more than lives. We will lose ourselves.

Humour didn’t destroy Nigeria.

But our refusal to confront reality might.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

And if we keep turning tragedy into entertainment, then one day, we will wake up to a country where nothing shocks us anymore; not even our own collapse.

Nigerians are the happiest set of humans, they say.

But maybe we’re not happy.

Maybe we’re just numb.

You may also like...

Arsenal's Set-Piece Supremacy: Record Corner Goals Boost Title Bid

Arsenal extended their Premier League lead to five points with a 2-1 victory over Chelsea, scoring both goals from corne...

Studio Shake-Up: Netflix Boss Slams Paramount's 'Irrational' Warner Bros. Bid as Producers React to Merger Mania!

Hollywood producers at the Producers Guild Awards offered mixed reactions to the Paramount-Warner Bros. Discovery merger...

Scream 7 Slays Box Office: Horror Franchise Shatters Records with Massive Global Debut!

"Scream 7" has slashed its way to a record-breaking box office debut, raking in $97.2 million globally, making it the hi...

Tehran's Turmoil: How Mideast Conflict Ignites Africa's Fuel Crisis and Soaring Living Costs

The escalating conflict in the Middle East, particularly involving strikes on Iran, is generating significant economic a...

Tigray Leader's Dire Warning: Ethiopia Teeters on Brink of War Amid Escalating Dispute

Widespread peaceful demonstrations have taken place across Tigray, Ethiopia, protesting recent decisions by the House of...

NAACP Image Awards: Viola Davis's Unforgettable Speech, Tabitha Brown's Fashion Statement, and Wunmi Mosaku's Historic Win!

The 57th NAACP Image Awards in Pasadena celebrated significant achievements, with Wunmi Mosaku winning Best Supporting A...

CWG Unleashes Digital Transformation Conference for Public Sector

CWG Plc is set to host a pivotal digital transformation conference on the 17th of this month, targeting Nigerian public ...

Middle East Meltdown: UK Scrambles to Evacuate 94,000 Citizens as Iran Conflict Grounds Flights

The Middle East is in crisis, with Iranian strikes causing widespread airspace closures and massive global flight disrup...