Nǐ hǎo Nigeria: A Critical Reflection on Integrating Mandarin into Our Educational Landscape

“Nǐ hǎo, Nigeria.”

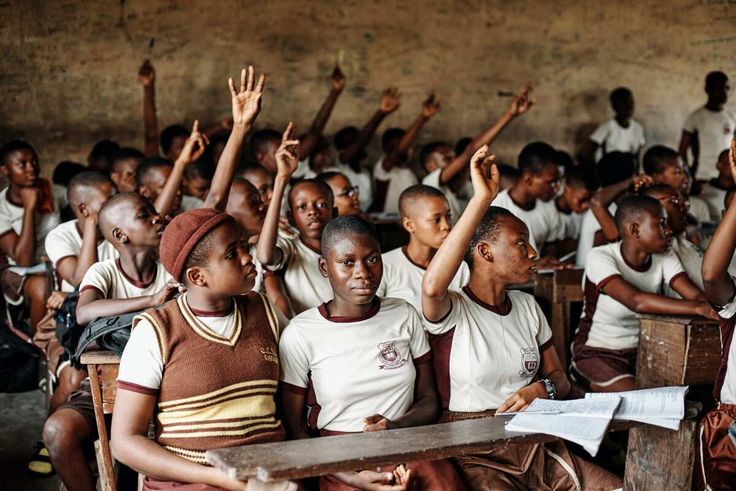

The phrase means “Hello, Nigeria” in Mandarin Chinese. Imagine walking into a classroom in Lagos or Kano and hearing a teacher greet students that way. Some children might giggle. Others might reply timidly, their tongues stumbling over unfamiliar syllables. For them, this is no longer just an experiment or cultural exchange. It is official. Mandarin has entered the Nigerian classroom as part of the new senior secondary curriculum.

It is a bold decision, one that sparks both curiosity and controversy. What does it mean when a nation that boasts over 500 indigenous languages decides to embrace a foreign one at such a formal level? Is this a leap toward global competitiveness, or a quiet concession to globalization that risks sidelining what is already fragile?

This op-ed does not aim to cheerlead or condemn. Rather, it seeks to ask, reflect, and challenge.

Why Mandarin, and Why Now?

Nigeria and China share a complicated but steadily growing partnership. China is Nigeria’s largest trading partner, and by 2023, trade between both nations was estimated at over $22 billion annually. Chinese companies have built railways, airports, and power projects across Nigeria.

In 2021, a Chinese loan financed the Abuja–Kaduna railway, sparking debates about debt dependency but also highlighting how deeply the relationship had sunk its roots.

From the government’s perspective, adding Mandarin to the school curriculum is not just about language. It is about strategy. Language is currency. It is diplomacy. It is the bridge to trade negotiations, scholarships, technology exchanges, and soft power. If Nigerian students can communicate directly with their Chinese counterparts, they gain access to opportunities that might otherwise remain distant.

But behind the strategy lies a dilemma: are we equipping our children for global competition, or are we planting seeds that might slowly erode the soil of our cultural identity?

The Cultural Dilemma: Global Doors vs. Local Roots

Nigeria is one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world. UNESCO lists 27 Nigerian languages as endangered. Languages such as Ikom, Basa, and Ukaan are spoken by fewer and fewer children each year. In some communities, parents actively encourage English over the local tongue, fearing their children will be “left behind” if they cannot operate in the global lingua franca.

Into this fragile landscape comes Mandarin. It is a language spoken by over a billion people worldwide, a language of commerce and global politics. Yet, its arrival raises haunting questions:

Should we be teaching Mandarin while indigenous languages slip into extinction?

Will students remember Igbo proverbs if they are busy memorizing Chinese characters?

Are we preparing global citizens who risk losing touch with their roots?

The tension is not new. During colonial rule, English was imposed as Nigeria’s official language. It unified the country administratively but fractured cultural continuity. Today, many urban Nigerian children struggle to speak their parents’ native tongues fluently. Introducing Mandarin could, for some critics, be repeating the cycle, an embrace of external influence at the expense of internal preservation.

But others argue differently. They insist that global engagement does not have to erase local heritage. A child can greet her grandmother in Tiv and still draft an email in Mandarin. The real issue is not whether Mandarin should be taught, but whether equal energy is invested in revitalizing indigenous languages.

The Practical Realities: Who Will Teach, Who Will Learn?

Grand policy announcements often stumble at the level of implementation. Nigeria’s education system already struggles with overcrowded classrooms, underpaid teachers, and scarce resources. Introducing Mandarin into this fragile ecosystem is ambitious, but ambition without infrastructure is fragile.

At present, much of the Mandarin instruction in Nigeria is supported by Confucius Institutes,cultural and educational centres established by the Chinese government. There are active institutes at the University of Lagos and Nnamdi Azikiwe University. These centres restrained a modest number of Nigerian teachers, but the scale is still far from what would be needed for a nationwide roll-out.

Let’s say a rural secondary school in Zamfara or Cross River, where even English and Mathematics teachers are in short supply. How likely is it that students there will receive consistent Mandarin instruction? Will Mandarin become another elite privilege, accessible mostly to urban schools in Abuja and Lagos, while rural communities lag behind?

Education experts also warn of curriculum overcrowding. Nigerian students already juggle heavy timetables. Introducing another subject without reducing or restructuring existing ones risks overwhelming learners and lowering overall quality.

And then there is the question of motivation. Will Nigerian students truly see value in learning Mandarin, or will it become another subject to be memorized for exams and forgotten soon after?

The Economics of Language: Opportunity or Costly Gamble?

Advocates of Mandarin instruction frame it as an investment in human capital. They argue that Nigeria must look ahead: China will continue to shape global trade, technology, and geopolitics. Proficiency in Mandarin could be a ticket to international jobs, scholarships, and competitive business advantages.

But skeptics urge a harder look at the numbers. Training teachers, importing learning materials, and establishing “Chinese Corners” in schools are costly ventures. Nigeria already spends less than 7 percent of its national budget on education, below UNESCO’s recommended 15–20 percent. Should scarce resources be funneled into Mandarin while many schools lack basic infrastructure like desks, textbooks, or electricity?

Consider this: if the same funds were used to digitize and preserve endangered Nigerian languages, thousands of children could access e-learning apps in their mother tongues. Research shows that students learn faster and retain better when taught in their mother language. This, in turn, could improve literacy and comprehension across all subjects, including science and mathematics.

The economic question, then, is not only whether Mandarin opens doors, but whether it opens more doors than reinforcing literacy in English and preserving indigenous languages would.

Toward a Balanced Future: Coexistence, Not Competition

Perhaps the way forward is not an either-or choice. A balanced approach is possible. Nigeria can embrace Mandarin for global engagement while also revitalizing indigenous languages for cultural preservation. The key lies in policy balance and smart implementation.

For instance, South Africa made Mandarin an optional subject in schools in 2015, sparking heated debate. Today, it is offered as an elective, not a compulsory subject, allowing interested students to pursue it while others focus on indigenous languages. Nigeria could adopt a similar model, ensuring Mandarin complements rather than competes with local language promotion.

Another path is to leverage technology. Imagine mobile apps where children learn Yoruba folktales or Tiv riddles in interactive formats, alongside Mandarin vocabulary games. Partnerships with local universities could ensure that investment in foreign language teaching is matched with investment in digital preservation of local languages.

Finally, the government must engage in honest dialogue with communities. Educational reforms should not be imposed from above but shaped by consultation with parents, teachers, linguists, and cultural leaders. Only then can Nigeria craft a curriculum that respects its roots while reaching for the skies.

Conclusion: The Reflective Question

“Nǐ hǎo, Nigeria” sounds polite, even welcoming. But it also carries a deeper echo. It forces us to ask: What kind of Nigeria do we want our children to inherit?

One where they can negotiate contracts in Beijing but cannot interpret their grandmother’s proverb? Or one where they can do both, where global fluency coexists with cultural rootedness?

The introduction of Mandarin into Nigerian schools is more than a curriculum tweak. It is a mirror held up to our educational priorities, our cultural anxieties, and our aspirations for the future.

As a nation, we must look into that mirror with honesty. We must ask ourselves whether we are preparing children merely to say “hello” to the world, or to say “hello” to the world without ever forgetting how to greet their ancestors at home.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...