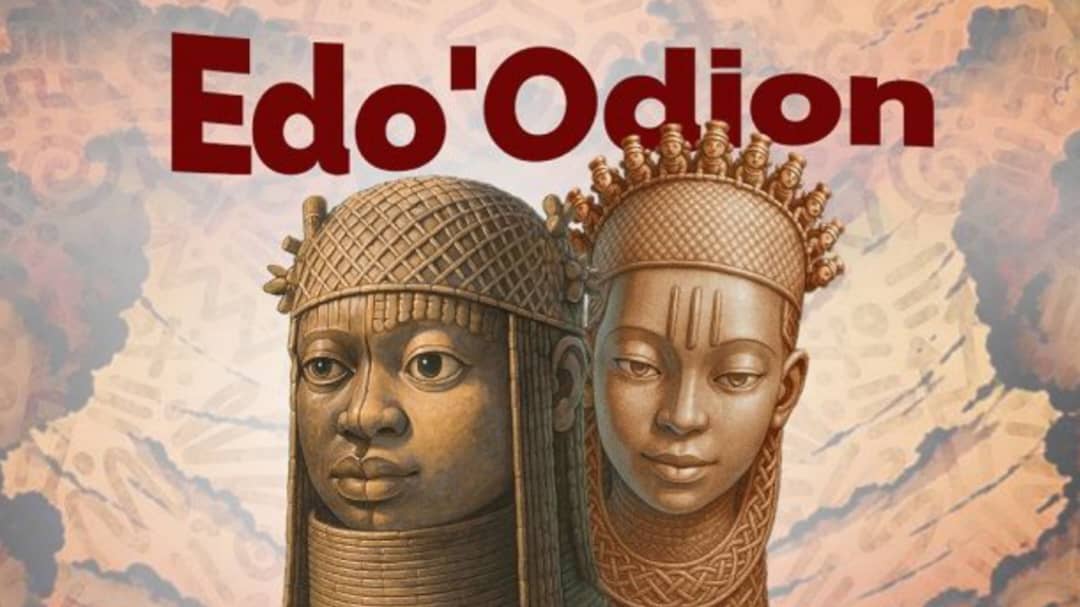

Benin City’s Historical Urban Planning: The Architecture of an African Powerhouse

Long before the pressures of modern expansion reshaped the landscape of southern Nigeria, Benin City had already earned a reputation that travelled far beyond West Africa. Early European visitors wrote about its unusually wide streets, the symmetry of its layout, and a palace complex that dominated the centre with quiet authority.

The impression they captured was of a city planned with intention, a place where political order, architecture, and everyday life were tightly woven together. In many ways, the echoes of that structured past still linger beneath today’s urban noise, reminding us that sophisticated city design on African soil is not a recent invention.

The Structure Behind Benin’s Early Urban Order

The ancient Kingdom of Benin developed a highly organised model of urban planning that astonished early visitors and continues to impress researchers today. Located in present-day Edo State in southern Nigeria, Benin City served as the political, cultural and economic centre of one of Africa’s most sophisticated pre-colonial states. Its carefully structured streets, monumental earthworks and refined administrative systems reveal a civilisation that placed order, efficiency and artistry at the heart of its identity.

Accounts from European travellers in the 15th and 16th centuries, especially Portuguese officials and traders, consistently described the city as strikingly planned. They noted the presence of long, straight avenues that cut across the capital, leading directly to the palace complex. These descriptions appear in early travel reports documented in the Journal of the Royal African Society and later supported by archaeological inquiries. A widely referenced historical summary can be found in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which discusses Benin’s urban layout and political organisation.

At the centre of the city stood the Oba’s Palace, an architectural and administrative masterpiece surrounded by courtyards, shrines and spacious compounds. Researchers at UNESCO confirm that the palace once housed numerous ceremonial spaces and served as the administrative heart of the kingdom, reflecting Benin’s political complexity and cultural depth. This central placement of the palace reinforced its role as both the physical and symbolic core of the state.

Surrounding the capital were the famed Benin Walls and Earthworks, also known as Iya. These structures, a massive network of ditches and ramparts, formed one of the largest earthwork systems ever constructed before the mechanical age. Archaeologist Patrick Darling, in a widely cited report, described them as “the world’s largest single archaeological phenomenon.” A detailed overview of these earthworks can be found through academic summaries on the British Museum’s information page. When measured collectively, the earthworks stretched for thousands of kilometres, enclosing villages, districts and farmlands in an intricate pattern of protection and organisation.

Guilds, Craftsmanship, and the City’s Cultural Engine

The kingdom’s administrative system also shaped its urban structure. Benin operated through a hierarchy of chiefs, guilds and palace officials who oversaw trade, security, construction and craft industries. One of the most notable institutions was the guild system, with each guild responsible for a specialised craft. The bronze-casting guild, known for producing the world-famous Benin Bronzes, played a crucial role in both the artistic identity and political narrative of the kingdom.

These bronzes, actually brass works, recorded history, honoured past Obas, and served ceremonial functions. Their precision, narrative skill and metallurgical sophistication make them some of the finest artworks in pre-modern African history. Institutions like the Smithsonian continue to highlight their material composition and cultural significance, offering detailed analysis and verified research.

Beyond artistry, Benin’s city structure demonstrated an impressive level of social organisation. The positioning of compounds, market squares, streets and guild quarters showed an intentional pattern that balanced everyday life with administrative efficiency. The city was not only a political seat but also a thriving economic environment supported by agriculture, trade routes and specialised labour.

For centuries, this structure remained strong, until the British invasion of 1897, which resulted in the destruction of many buildings and the forceful removal of thousands of cultural objects. Verified historical records of this event are preserved in the British Library’s documentation of the expedition and its aftermath. Although the physical landscape changed, the memory of Benin’s architectural brilliance endures through historical studies, surviving earthworks and recovered artworks.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Today, researchers continue to examine Benin City not only as a historical site but as evidence of pre-colonial African innovation. Its sophisticated layout, monumental fortifications and expertly governed society challenge long-standing misconceptions about urban planning on the continent. For many, the kingdom stands as a testament to Africa’s deep-rooted traditions of governance, architecture and cultural excellence.

Benin City’s urban planning remains a powerful reminder that African civilisations developed complex and advanced city systems long before modern urban models emerged. The story of Benin is not just a preserved chapter of the past, it is an enduring example of African ingenuity, resilience and heritage.

What survives of old Benin in its earthworks, carved plaques, recorded observations, and archaeological findings shows a civilization that approached city building with clarity and long-term vision. Its avenues, guild quarters, and royal compounds did more than organise space; they reflected a system concerned with stability, duty, and shared identity. Looking back at this heritage broadens the picture of Africa’s urban history, proving that thoughtful planning and complex governance structures were already thriving here centuries before outside contact.

You may also like...

Shock Doping Suspension: Chelsea Star Mudryk Spotted Training at Non-League Club

Chelsea winger Mykhailo Mudryk is training at non-league club Uxbridge FC amidst his provisional suspension for a doping...

World Cup Chaos: Super Eagles vs Team Melli Clash Faces Roadblock Amid Iran Doubts

A friendly football match between Nigeria's Super Eagles and Iran faces uncertainty due to an escalating crisis in Iran,...

Half-Century Celebration: Hong Kong Film Festival Honors Legends!

The Hong Kong International Film Festival marks its 50th anniversary with a retrospective celebrating Chinese-language c...

Director's Fiery Condemnation: Rasoulof Labels Khamenei 'Most Hated Figure'!

Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof has strongly condemned the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was r...

Innovative Fusion: French Artist Blends Greek and Rwandan Traditions

French artist and architect Guillaume Sardin, based in Paris, integrates Rwandan history and visual culture into his art...

Zimbabwe's Top Artists Honored: Full NAMA Awards Winners Revealed!

The National Arts Merit Awards (NAMA) celebrated "Fearless Creativity" at a glittering ceremony, honoring top Zimbabwean...

Max Minghella Decodes Iconic Rivalry: 'Industry' Star Connects Batman-Joker to Whitney's Downfall!

Max Minghella delves into his role as the enigmatic Whitney Halberstram in "Industry" Season 4, detailing the character'...

HGTV Stars Spill Secrets: D'Arcy Carden and Sherry Cola Unveil Wildest Vacation Spot on New Show!

HGTV's "Wild Vacation Rentals" features comedians D'Arcy Carden and Sherry Cola touring America's most outrageous rentab...