Before Streaming Took Over: Saying Goodbye to the Home Stars We Loved

You could walk into a small shop and find Aki na Ukwa beside Blood Sisters. People bought movies like groceries, three for ₦500 each one promising drama, tears, and laughter in equal measure.

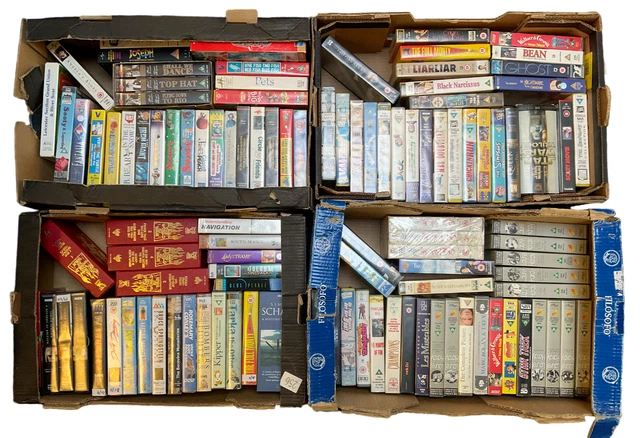

There was a time when film wasn’t a click away. When Saturday nights meant dimmed lights, a plugged-in VHS player, and the whirring sound of a cassette finding its track. That was when Nollywood, as the world would later call it, was more than an industry, it was a feeling.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, home videos shaped how Africans told stories. They captured the rawness of everyday life markets bustling with traders, mothers fighting for their children’s future, and men chasing dreams through Lagos traffic. Everyone could relate.

Films like Living in Bondage and Osuofia in London weren’t just blockbusters; they were mirrors reflecting the African reality. Back then, a film didn’t need cinema halls or red-carpet premieres. It needed heart, truth, and a community eager to see itself on screen.

That was the power of home videos, storytelling that felt personal, tangible, and ours.

When Stories Lived on Shelves

Every Nigerian home once had a stack of plastic VHS cases or later, pirated VCDs sold at corner kiosks. Those shelves weren’t just for movies, they were archives of family laughter and memory.

These home videos united neighbourhoods. Families gathered around small screens, shouting at villains, laughing at mischievous sidekicks, and learning life lessons tucked in every plot twist. It was entertainment, but also education, cultural preservation disguised as drama.

But behind the joy was a thriving ecosystem. Producers, marketers, editors, and street vendors formed a grassroots cinema network that made Nollywood the second-largest film industry in the world. The model was simple: low budgets, fast shoots, relatable stories. The reward was massive, a cultural movement that defined a generation.

The transition didn’t happen overnight. First came DVDs, then online platforms promising crisp visuals and convenience. When Netflix expanded to Africa in 2016, the landscape shifted forever.

Suddenly, stories no longer needed kiosks, they needed data. The tactile joy of holding a film in your hands gave way to swiping thumbnails. The communal ritual of watching together turned into solitary streaming sessions.

For many African filmmakers, this was progress: better budgets, global audiences, international recognition. Series like Blood Sisters and Shanty Town found space on major platforms, signaling that African stories had finally “made it.”

But in the background, the old home video model that intimate, accessible kind of cinema began to die quietly.

The Cost of Convenience

Streaming offered what the home video couldn’t: ease. No scratched discs, no waiting days for new releases. But it came at a cost, a loss of connection.

Back then, buying a home video was an event. You met the vendor, debated the plot, swapped movie recommendations, and sometimes even argued over actors. Now, a new Nollywood release appears on your screen with no sound of excitement, just another title in a digital queue.

Moreover, the rise of subscription services means access is no longer equal. A generation that once bought films for a few hundred naira now needs stable internet and international payment cards. The gap between the audience and the art widened, leaving behind the same local fans who made Nollywood flourish in the first place.

Even for creators, the rules changed. Where once a filmmaker could shoot a movie in ten days and sell thousands of copies on the street, now they face corporate filters, content policies, and budgets dictated by what’s “marketable.” The home video freedom to experiment, to improvise, to tell unapologetically African stories is harder to sustain.

Still, something about that era refuses to die. Every time an old VHS cover resurfaces online, nostalgia floods the comments. People remember the awkward edits, the dramatic music, and the lessons tucked beneath the chaos.

Filmmakers like Tunde Kelani, who directed classics such as Thunderbolt (Magun), have continued to preserve that spirit through hybrid platforms like Mainframe TV. Others, such as Kunle Afolayan, blend old-school storytelling with new-age production in films like Aníkúlápó, proving that Africa’s cinematic roots can evolve without erasure.

Even outside Nigeria, echoes of the home video era persist. In Ghana, Kenya, and Tanzania, filmmakers who once distributed DVDs locally now stream through Showmax Africa or YouTube channels that cater to regional audiences. They carry with them that same authenticity, a belief that storytelling starts in the community before it reaches the cloud.

Interestingly, the decline of physical home videos has sparked a cultural comeback, not in the way anyone expected. Across TikTok and YouTube, young Africans remix old scenes from vintage Nollywood films, turning them into viral sound bites and memes.

What was once low-budget drama now inspires digital nostalgia. Clips of Genevieve Nnaji’s emotional scenes or Patience Ozokwor’s legendary scolding moments circulate globally, introducing younger generations to an era they never lived.

That’s the irony: streaming may have killed the home video star, but it also immortalized them.

Between Pixels and Memory

Africa’s film industry now stands between two worlds, one is defined by the simplicity of the past, and the other by the sophistication of the present.

Yet, even as the streaming age takes over, the essence of those old home videos the warmth, the humor, the emotional honesty remains embedded in every frame. They remind us that cinema is not just about resolution or reach. It’s about feeling.

Those crackling sounds from an old cassette, the flickering screen during a power cut, the entire street crowding around one TV and these are the true markers of a generation’s bond with storytelling.

Streaming has given African filmmakers a bigger stage, yes. But it has also made audiences long for something money can’t buy: intimacy.

In the end, the home video star didn’t really die. It evolved and scattered across digital timelines, reborn through nostalgia, and carried in the hearts of those who lived through its golden age.

As Africa’s storytellers embrace global technology, one truth remains: the home video era was not just about film. It was about family, friendship, and identity. And no matter how advanced our streaming becomes, that reel of memory will never stop spinning.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...