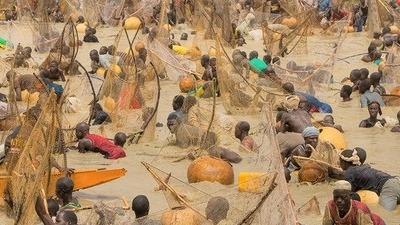

Africa Isn't Poor, It Is Undervalued: The Case Against Global Credit Ratings

Take a look at this scenario for a second. Germany borrows $1 billion at, let’s say, a 2.29% interest rate. Over ten years, it pays back roughly $229 million in interest.

Now imagine Zambia borrowing that exact same amount except it is charged a rate of, let’s say, 22.5%. Its interest bill is $2.25 billion. That is nearly ten times more, for the same loan, from the same global market.

The difference is not rooted in how well Zambia manages its money. It is rooted in perception. And the people shaping that perception are three American companies — Moody's, S&P Global Ratings, and Fitch Ratings — otherwise known as the Big Three credit rating agencies.

What Even Is a Credit Rating?

Think of it like a financial report card. Just as your credit score tells a bank whether to trust you with a loan, sovereign credit ratings tell global investors how risky it is to lend money to a country.

The Big Three assign letter grades where AAA is the gold standard and anything below BBB is basically classified as "junk" or speculative grade.

And the frustrating thing is as of today, only four African countries — Botswana, Mauritius, Morocco, and South Africa — hold investment-grade ratings. The rest are basically labeled junk, regardless of their economic trajectory or reform efforts.

If these ratings were just academic grades, it would have been bearable. But they are not. They dictate the terms on which countries can borrow.

A lower rating means higher interest rates, which means more money drained from public budgets, money that could have built hospitals, schools, or roads, going straight to debt servicing instead.

The Bias Hidden in the Methodology

According to a joint study by the UNDP and AfriCatalyst, African nations pay, on average, 1.5 percentage points more than countries with similar economic fundamentals.

The Big Three have long been criticized for applying a Western economic framework to African economies, without adequately accounting for their unique dynamics.

Factors like the rapid growth of mobile money, the resilience of informal economies, and regional trade integration rarely receive the same weight as traditional debt-to-GDP ratios or governance metrics filtered through a Western lens.

The problem is also logistical. Fitch closed its only African office in 2015. Most Big Three analysts covering the continent are based in Europe, the US, or Asia, visiting for a maximum of two weeks per year.

The gaps this creates are real and demonstrable. Moody has once downgraded Nigeria's outlook, only to reverse the decision within seven months after the government pushed back, arguing the agency had misread the domestic environment.

In Cameroon, rating agencies held incorrect ratings for nearly nine months, based on unverified debt payment information. These are not small errors. These are systemic failures with billion-dollar consequences.

The Human Price Tag

The African Risk Premium, that extra interest tacked onto African government loans, is a policy that costs lives.

Africa's total external debt sits at approximately $1.1 trillion, with the continent spending around $163 billion annually just to service it. More than 50 low- and lower-middle-income countries are spending more on debt repayment than on public health or education.

A 2023 UNDP study found that African countries could save up to $74.5 billion if ratings were based on less subjective assessments.

Zambia's 2020 default triggered immediate downgrades from Fitch and S&P. But the crisis stemmed primarily from structural vulnerabilities, overdependence on copper exports, exposure to commodity price swings, and pandemic-era shocks.

The framing internationally was one of fiscal failure. The reality was far more complex.

Something New Is Coming

Pushback is growing and it is getting organized. The Africa Credit Rating Agency (AfCRA), backed by the African Union and supported by the UNDP and AfriCatalyst, is being developed as a context-aware alternative to the Big Three.

It won't replace Moody's or S&P overnight, but it offers something critical: African economies assessed on African terms, by people who understand the ground realities.

Alongside this, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has the potential to fundamentally shift the continent's risk profile. By integrating 54 countries into a single market of 1.4 billion people, AfCFTA could diversify export bases, strengthen fiscal buffers, and reduce overexposure to global commodity shocks which are all factors that directly influence how risky a country appears to outside investors.

The Bigger Picture

The truth is the credit rating system was not designed with Africa in mind. It was built for Western markets, refined for Western economies, and operationalized by Western institutions.

Using it uncritically to assess African governments is like grading a marathon runner on their swimming technique and then charging them more for running shoes.

Africa is not a charity case waiting for better ratings. It is a continent with immense natural resources, a young and growing population, and some of the world's fastest-growing digital economies. The problem is not the continent's potential, it is about who gets to define its creditworthiness, and the financial system's stubborn insistence that only three American companies should have that power.

Ratings are, as one economist put it, opinions. It is time the world started demanding that those opinions be better informed and that Africa stops paying the price when they aren't.

You may also like...

Africa Isn't Poor, It Is Undervalued: The Case Against Global Credit Ratings

Global credit ratings may be costing Africa billions. This article examines how biased risk assessments inflate borrowin...

Africa Is Independent. So Why Are Our Judges Still Wearing Colonial Wigs?

It’s been 50 years since Britain left Africa, yet colonial wigs remain in many courtrooms. The history, countries that a...

Kemi Badenoch And Josephine Macleod: Nigerians Making Waves in UK Politics

Nigerians are rising in UK politics, from Kemi Badenoch’s national leadership to Josephine Macleod’s Scottish candidacy....

Balancing Work, Life And Parenting Without Guilt

Balancing work, life, and parenting doesn’t require perfection. Focus on what matters, set boundaries, and care for your...

Can You Trust a Rebranded Crypto Company? Nexo's Return Raises Bigger Questions

After regulatory trouble and a $45M fine, Nexo is back in the U.S.—but can investors trust a rebranded crypto company, e...

Transfer Speculation Grows as Manchester United Target Liverpool’s Mac Allister

Football's summer transfer window is heating up with major European clubs eyeing key players. Manchester United is repor...

Two Premier League Heavyweights Competed for Klopp Following Liverpool Departure

)

Jürgen Klopp's agent, Marc Kosicke, revealed that Chelsea and Manchester United pursued the German manager after his Liv...

Tom Hardy’s Crime Series Soars as Season 2 Wins Fans’ Praise

Emmett J. Scanlan teases an "insane" Season 2 for Guy Ritchie's 'MobLand', promising heightened drama and the return of ...