Nigerian Court Sagas: Ejigbadero, A Story of a Ghost.

Who are Raji Oba and Ejigbadero?

In Nigerian law, words spoken on the brink of death once held a spectral weight—acknowledged, yet not always decisive. That changed forever in 1975, when one man’s final breath echoed not only across a courtroom but across history. The case of Jimoh Ishola, alias Ejigbadero, marked the moment Nigeria's judiciary stopped treating dying declarations as whispers from the grave—and instead began treating them as testimony.

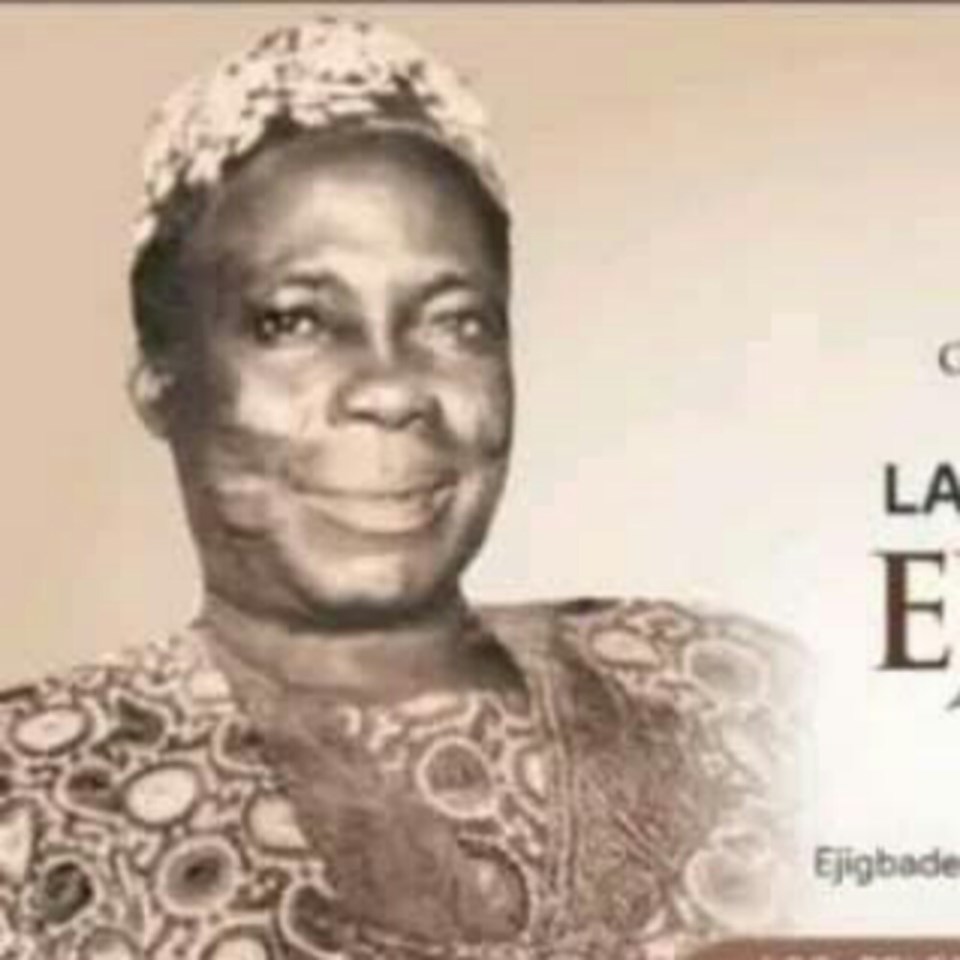

Ejígbádéró, meaning "The (spirit of) rain upheld the crown," or in some translations, "mighty ghost supporting the crown," was no ordinary man. He possessed a presence that commanded both admiration and unease—his voice smooth with charm, his gaze sharp and unreadable. Though he made his fortune manufacturing nails, his true ambition was fixed on something far older and harder to bend: land.

Back then, Alimosho—a village slowly being swallowed by the sprawl of Lagos—was next on his list. But what he called investment, the villagers called invasion. The village was a relic, a patchwork of brown huts and cocoa farms clinging to ancestry. And at its heart stood one man—Raji Oba, the farmer who refused to sell. Today, as you go from Iyana Ipaja to Egbeda in Alimosho — Raji Oba Street is to your left.

Image: The Late Jimoh Ishola, aka Ejigbadero

The Incident of 22nd August 1975: A Factual Recount

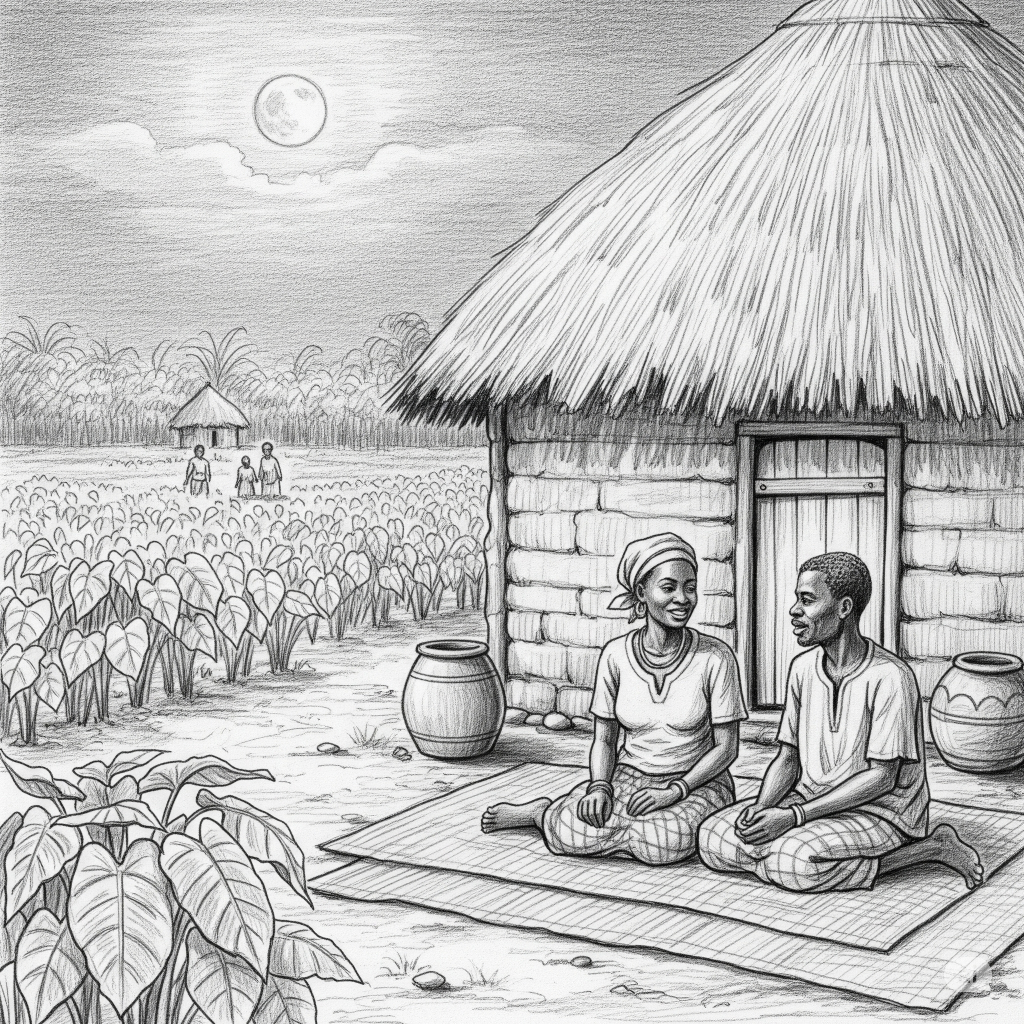

The murder of Raji Oba happened around 8 p.m. in Alimosho village. It was the kind of night poets might call gentle, when the moon hung low and heavy, casting silver shadows across red earth and whispering rooftops.

Sabitu Raji Oba, the wife of Raji Oba, had just returned from the market. She carried with her more than yams and peppers—she carried a warning. Her voice was urgent, trembling as she told her husband that she had seen them—him—on the village path: Ejigbadero, flanked by unfamiliar faces. They moved like a storm waiting for its cue.

She and her husband sat together in the open air, as many villagers did on nights like this—when the heat of the day still clung to the skin, and the moon was bright enough to see each other's faces without the flicker of lanterns.

A stillness spread over the earth, the kind that feels like breath held too long.

Then it cracked.

A single gunshot tore through the air, sharper than thunder, crueler than lightning. Sabitu barely had time to scream. Her husband groaned, then slumped, sliding from his chair like a sack of cassava. Blood darkened the soil beneath him, thick and quick—life leaking into the ground. He had been shot in the head.

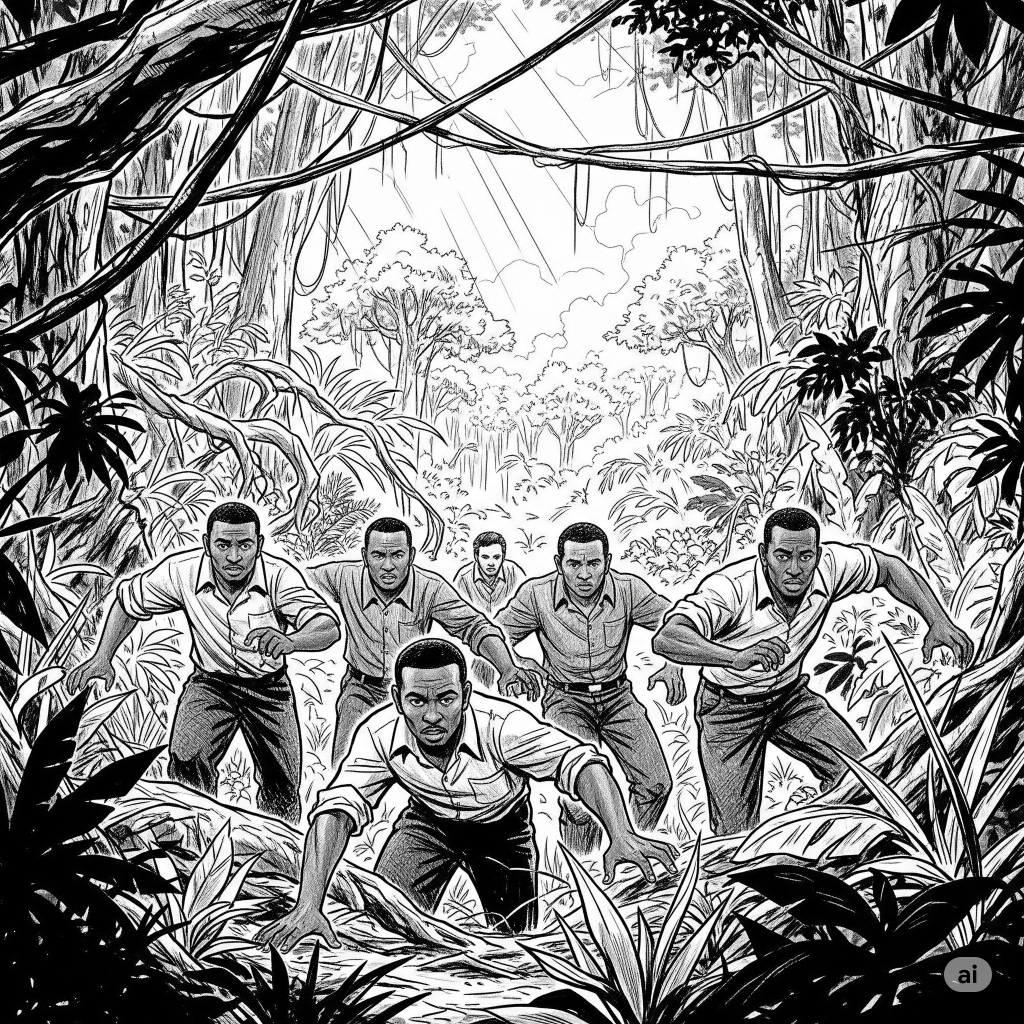

Smoke curled from the nearby thicket, faint but unmistakable, gunpowder still clinging to the night air. Sabitu’s eyes scanned the direction of the shot—and there they were: six shadows sprinting toward the bush, their movement frantic and ungraceful. And at the rear, a figure stood out to her like a scar on skin. Broad shoulders, a confident gait, and English clothes—a short-sleeved shirt tucked into trousers.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

She had seen that frame before.

It was Ejigbadero.

Words Against Words

Just a few moments before a man’s blood soaked the earth in Alimosho, Jimoh Ishola—known on the streets as Ejigbadero—sat at the heart of a joyous soirée(party).

His child’s naming ceremony was being held in his family compound, some distance away from Alimosho village. Time? 8 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. This is the critical window during which Ejigbadero claimed he was at the naming ceremony. Guests at the party swore he did not leave the event during this time, which the defense used to argue he couldn’t have been at the murder scene.

It’s the 1970s, in a neighbourhood primarily influenced by Yoruba culture, so we may assume that the air was thick with the aroma of Asun (peppered goat meat), steaming moi moi, and beer. Somewhere in the parlor might sit a basket of gifts for the child—such as palm oil, sugar cane, pepper, honey and bitter kola.

Laughter would have filled the air, perhaps colliding with the brassy blare of Victor Uwaifo’s Joromi, spinning from a dusty turntable. You might find adults in small clusters likely mulling over General Murtala’s latest decree, the growing fuel queues, or the buzz of the upcoming Festac ’77.

Men would be dressed in flared trousers and vibrant ankara bùbá and sòkòtò sets, their afros combed high, their voices deep with politics and gossip. The women would dazzle—headties towered like regal crowns, their lace iro and bùbá glittering in the dim lantern light, as they enjoyed trays of fried plantain and puff-puff.

Of course, here is the indisputable fact: in the midst of it all was Ejigbadero, father of the day, draped in the ever-regal agbádá. This seemingly unimportant fashion detail would become crucial to the murder investigation of Raji Oba and would make Ejigbadero live up to his alias as a ghostly and evasive figure.

The Courtroom: A Battle of Accounts

It was not the dusty fields of Alimosho but the solemn halls of justice where the true battle would unfold. The courtroom was no longer just a place of law—it became a stage where memory and motive, grief and guilt collided in brutal theatre. At the center of it all sat the accused: Jimoh Ishola—Ejigbadero. Cloaked now not in the grandeur of agbada, but in the shroud of suspicion.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

The prosecution came armed with more than grief—they came with testimony that cut deep. They painted a story of premeditation, of a man so consumed by land that he turned joy into a smokescreen and used the night to settle an old score.

Sabitu maintained her stance in court: she had seen him. Not his face, no. But his back. His stride. His clothing. English dress—short-sleeved shirt tucked into trousers. The same man she had warned her husband about. The same man who, just before the shot, she had seen prowling through her village.

But Ejigbadero did not go down quietly. The defense struck back, weaving a tale of innocence, of misidentification, of time and place. Their argument was clear: Ejigbadero was not in Alimosho when the shot was fired—he was far from the scene, surrounded by family and friends, basking in the warmth of his newborn child’s naming ceremony. They offered an alibi, supported by guests who swore under oath that the accused had not left the party between 8 p.m. and 9:30 p.m. More importantly, they pointed to what he wore that night—not English dress as the witness claimed, but an agbada.

The agbada, a wide-sleeved robe that billows with dignity, originates from the clothing styles of various trans-Saharan and Sahelian groups in West Africa. It was not a garment that could be easily mistaken for a short-sleeved shirt and trousers. It was grand, flowing, and unforgettable.

Yet something in the air shifted. Witnesses for the defense contradict one another—slightly, subtly, but enough for the trial judge to suggest rehearsed loyalty rather than truth. Time blurred in their recollections, and shadows crept into their certainty.

Meanwhile, the prosecution brought more than the widow’s words. A trail of corroborating evidence was laid out: the sighting of Ejigbadero earlier in the day, his known quarrel with the deceased, and the eerie swiftness with which he vanished from Lagos following the murder—leaving behind his house, his factory, and the very child whose naming ceremony was said to anchor his innocence.

A Twist of Fate

Then came the final piece of evidence: a dying declaration from Raji Oba himself. Despite the gunshot wound to his head, he remained conscious long enough to speak. While some dismissed it as a fabrication by his wife, others accepted it as truth. In her presence, he had reportedly said, “Ejigbadero mo ri e o,” which translates to “Ejigbadero, I see you.”

Although dying declarations had once been treated as fragile threads of hearsay, this one—spoken moments after the attack, heard by the very woman who saw the shooter flee—stood as a spear of truth. Precedent, proximity, and corroboration gave it spine.

Several eyewitnesses provided crucial testimony regarding the events surrounding the shooting. Nimota Kelani, a neighbour, heard the alarm raised by the deceased’s wife and came outside, where she saw the accused running away toward the bush. She called out to him, reminding him that he had kept his "promise" to kill the deceased.

Rafiu Latifu, while returning to the village, saw a white Peugeot 504 station wagon parked by the side of a mosque near the deceased’s house and observed Ejigbadero, along with six other persons—one of whom was a woman—running out of a nearby bush toward the vehicle.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Lastly and most damningly, Kehinde Yekini, a security guard employed by Ejigbadero, testified that the Ejigbadero had informed him about the plan to kill the deceased and described how Ejigbadero left with a group to carry out the "operation," returning later that night.

The Verdict

The court was not a place for drama, but the air was electric when the verdict was read. Justice sowed no joy that day, only gravity.

Guilty. Ejigbadero—the ghostly force who upheld the crown—was sentenced to die.

So what do you think? Was Ejigbadero undoubtedly guilty or are there more loose threads to tie?

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...