Giants in the Desert: Africa's Telescopes In Astronomy

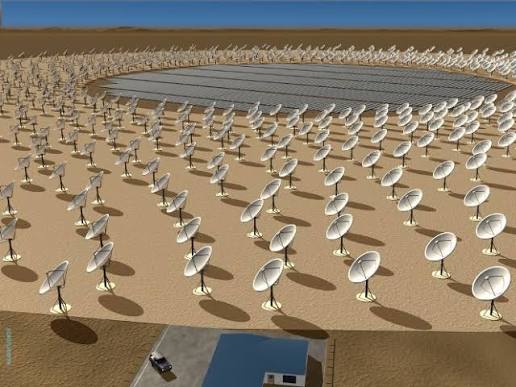

In the center of South Africa's Karoo desert, where silence stretches for kilometres and the night sky burns with unfiltered stars, a cluster of white dishes points upward. To locals, they're a curiosity– a network of enormous radio antennas rising from the dust. To scientists, they represent one of the most ambitious scientific undertakings in the world: the Square Kilometre Array, or SKA.

Completed, the SKA will be the world's largest and most sensitive radio telescope. It’s a global project led by the SKA Observatory (SKAO), co-hosted by South Africa and Australia, with support from partner nations across four continents. The question it aspires to answer is simple yet profound: how the universe began, how it came to be dominated by galaxies and stars, and are we truly alone?

For Africa, though, the telescope has become a sign of capability, an evidence that world-class science and technology can thrive on African soil.

From MeerKAT to the SKA

The story started with MeerKAT, a South African-built precursor to the SKA. Completed in 2018, MeerKAT’s 64 dishes were designed, a proof that African engineers and scientists could construct and operate a complex, globally competitive observatory. When they did this, they surpassed expectations.

Within the first few years of its completion, MeerKAT gained attention with several remarkable achievements.

Unveiling giant radio galaxies: The MeerKAT found massive galaxies, like the Inkathazo– trouble in isiXhosa– some of the largest ever recorded. The findings challenged previous assumptions about how common these enormous radio structures are.

Unveiling the heart of the Milky Way: MeerKAT created the sharpest radio image of the Milky Way's centre, unveiling hundreds of filamentary structures and deepening the insight into the magnetic environment around the central black hole of our galaxy.

Tracing hydrogen across space: By detecting faint hydrogen emissions, scientists use MeerKAT to study the formation, evolution, and interaction of galaxies, mapping cosmic structures billions of light-years away.

These achievements proved that Africa could not only host a world-class telescope but also contribute meaningfully to the frontiers of astronomy.

A New Model of Scientific Collaboration

The SKA project is transforming astronomy and the ecosystem supporting it. Its construction has become a case study in scientific capacity building: how large-scale research can foster skills, infrastructure, and local industries.

The African SKA Human Capital Development Programme, initiated in 2005, has funded more than a thousand bursaries, scholarships, and fellowships in such fields as astrophysics, electrical engineering, and computer science. Many of those early beneficiaries are now scientists, data specialists, and project managers who will help drive the next phase of the SKA.

But the collaboration goes far beyond South Africa. The African Partner Countries, including Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, and Zambia, are part of a network that's building the African Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) Network, linking smaller telescopes across the continent to work together as one giant virtual dish, increasing imaging precision to remarkable levels.

In Ghana, for instance, engineers transformed an abandoned satellite dish into a working radio telescope. In Namibia and Kenya, similar projects are now underway, combining training, infrastructure, and regional cooperation in ways that strengthen local economies.

Data, Connectivity, and Opportunity

Radio astronomy demands immense data processing power. Each SKA antenna produces huge volumes of data that have to be transported, cleaned and analyzed-a challenge that has been driving the development of High-Performance Computing and fiber-optic networks across Southern Africa.

What started out as an element of scientific necessity now benefits entire communities: towns such as Carnarvon, hitherto isolated, boast good connections to broadband, digital learning labs, and technology-based learning programs. These upgrades, catalyzed by the SKA infrastructure, foster a new generation of pupils well-versed in coding, robotics, and data analytics.

The impact extends into the private sectors, too. Engineers and technicians who had been trained on the SKA project have gone to take their expertise into telecommunication, renewable energy, and artificial intelligence companies. The result is a growing local industry of problem solvers shaped by one of the world's most data-intensive scientific projects.

What the SKA Will Explore

When fully operational, the SKA-Mid array in South Africa and its counterpart SKA-Low in Australia will work in tandem to answer some of the most challenging questions in physics and cosmology.

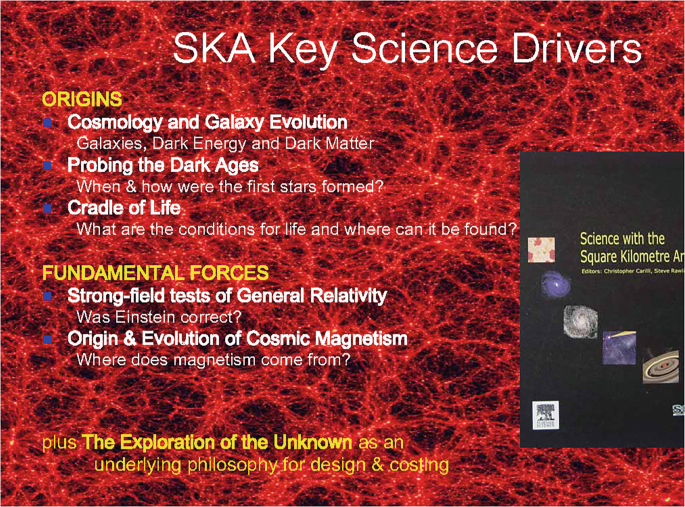

Gravity and relativity: The SKA will be able to test Einstein's General Relativity in gravitational environments unavailable to terrestrial experiments by the observation of pulsars orbiting black holes.

Mapping the evolution of galaxies: By using the 21-centimeter hydrogen line, researchers will map over a billion galaxies, creating a three-dimensional timeline of cosmic evolution that could help explain how dark energy drives the expansion of the universe.

The early universe: Because of the telescope's sensitivity, it will be possible to observe the first generation of stars and galaxies formed after the Big Bang-the so-called "cosmic dawn."

Search for life: The SKA will detect faint radio emissions and molecular signatures that could point to the chemical conditions for life beyond our planet.

The data from the telescope will be immense, comparable to the world's current total internet traffic per year; continuous innovation in computing and storage will be needed.

Local Impact, Global Implications

While the SKA's scientific objectives are universal, its impacts are very real and immediate in the areas surrounding the site. In the Karoo, local technicians maintain the arrays and support teams handle logistics, security, and data operations. Schools have been upgraded, and new skills programmes give residents access to opportunities in engineering and IT.

The project also underlines a new model of linking science with development: Instead of importing expertise, the SKA trained Africans to build and manage the technology. Ownership at the local level is redefining how international projects work on the continent, so that instead of resource extraction, knowledge is being created.

Africa's Emerging Role in Global Science

For the first time, Africa is leading a project that stands at the frontier of global discovery. Scientists from the continent aren't just participating; they're setting research priorities, designing instruments, and developing the data pipelines that will power the SKA.

This leadership will shift the global perception of African science. It will show that world-class research can emerge from the continent; African expertise is central to universal questions pertaining to existence, matter, and life's beginnings.

As one of the visionaries behind the project, Dr. Bernie Fanaroff, once said, the SKA isn't only about astronomy but about creating a scientific culture that drives development. Two decades later, that vision is materializing.

The Future of Discovery

The Karoo site is quiet by necessity; it's a protected radio-quiet zone where even a mobile phone signal can interfere with observations. But that isolation has turned it into one of the most data-rich locations on Earth.

When construction is completed in the 2030s, the SKA will produce images and measurements that will redefine how scientists see the universe. But long before that, it's already redefining how the world sees Africa. This project is, in fact, a shift in narrative-from dependence to innovation, from spectatorship to authorship. The discoveries made under African skies will belong to humanity, but the expertise that will make them possible will carry African names. And that, perhaps, is the most important signal the SKA will ever transmit. No, it doesn't matter either way.

Recommended Articles

From Addiction to Astonishing Health: Couple Sheds 40 Stone After Extreme Diet Change!

South African couple Dawid and Rose-Mari Lombard have achieved a remarkable combined weight loss of 40 stone, transformi...

Mugabe Scion's Shocking Arrest: Son of Late Dictator Detained in South Africa for Alleged Attempted Murder!

Zimbabwe's late former President Robert Mugabe's youngest son, Bellarmine Mugabe, has been arrested in South Africa on a...

Mugabe Family Scandal Explodes: Chatunga Arrested for Hyde Park Shooting Incident

Bellarmine Chatunga Mugabe, son of the late Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, has been arrested in Johannesburg follow...

Billions Invested As Cape Town Airport Kicks Off Mega Overhaul

Cape Town International Airport is embarking on a massive R21.7 billion renovation program set to begin construction in ...

Explosive Accusations: Ex-President Lungu's Family Fights Poisoning Allegations

Former Zambian President Edgar Lungu's burial remains mired in controversy months after his death, as his family and the...

A Nation's Uneasy Rest: Edgar Lungu's Burial Dispute Deepens with SA Court Ruling Looming!

A criminal investigation has been launched in South Africa into the death of former Zambian President Edgar Lungu, with ...

You may also like...

If Gender Is a Social Construct, Who Built It And Why Are We Still Living Inside It?

If gender is a social construct, who built it—and why does it still shape our lives? This deep dive explores power, colo...

Be Honest: Are You Actually Funny or Just Loud? Find Your Humour Type

Are you actually funny or just loud? Discover your humour type—from sarcastic to accidental comedian—and learn how your ...

Ndidi's Besiktas Revelation: Why He Chose Turkey Over Man Utd Dreams

Super Eagles midfielder Wilfred Ndidi explained his decision to join Besiktas, citing the club's appealing project, stro...

Tom Hardy Returns! Venom Roars Back to the Big Screen in New Movie!

Two years after its last cinematic outing, Venom is set to return in an animated feature film from Sony Pictures Animati...

Marvel Shakes Up Spider-Verse with Nicolas Cage's Groundbreaking New Series!

Nicolas Cage is set to star as Ben Reilly in the upcoming live-action 'Spider-Noir' series on Prime Video, moving beyond...

Bad Bunny's 'DtMF' Dominates Hot 100 with Chart-Topping Power!

A recent 'Ask Billboard' mailbag delves into Hot 100 chart specifics, featuring Bad Bunny's "DtMF" and Ella Langley's "C...

Shakira Stuns Mexico City with Massive Free Concert Announcement!

Shakira is set to conclude her historic Mexican tour trek with a free concert at Mexico City's iconic Zócalo on March 1,...

Glen Powell Reveals His Unexpected Favorite Christopher Nolan Film

A24's dark comedy "How to Make a Killing" is hitting theaters, starring Glen Powell, Topher Grace, and Jessica Henwick. ...