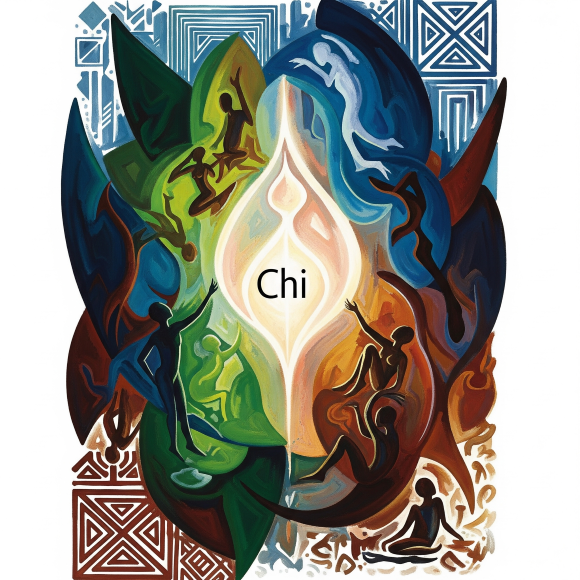

Understanding Chi: The Igbo God-Self

Among the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria, there is a word that is both intimate and cosmic, both deeply personal and broadly metaphysical: Chi. It is a term that resists simple translation, because it is not merely “soul,” nor simply “god,” nor strictly “destiny.” Chi is something like all three at once—a divine spark that accompanies each human being, shaping their life path while also reflecting their individuality. To understand Chi is to peer into the heart of Igbo cosmology, but it is also to glimpse a profound philosophy of selfhood that speaks across cultures and centuries.

A god That Is You

Image Credit: Unsplash

The Igbo believe that every individual is assigned a Chi at birth. This Chi is a personal deity, but unlike the high god Chukwu or the pantheon of ancestral spirits, the Chi is not external. It is intrinsic. One Igbo proverb puts it starkly: “Onye kwe, Chi ya ekwe”—If one agrees, their Chi agrees. In this terse statement lies the essence of Igbo metaphysics: your will and your Chi are intertwined, but not identical. The Chi is both your fate and your companion in shaping it.

The duality is striking. On one hand, Chi represents destiny, a predestined script written before you emerge into the world. On the other hand, Chi responds to human agency—it is not blind determinism but a partnership. Success and failure are therefore not entirely in the hands of the individual, nor entirely in the hands of the gods, but in the complex interaction between human striving and divine allowance.

Principles of Chi

If we are to distill Chi into principles, three emerge most clearly.

1. The Principle of Dual Responsibility.

In the Igbo view, the individual cannot wholly blame fate for misfortune nor wholly credit themselves for success. Both Chi and human effort must work in tandem. A proverb captures this balance: “Mmadu adịghị arụ ọrụ, Chi adịghị enyere ya”—If a person does not work, their Chi does not help them. Here, divine assistance is conditional on human exertion. The Igbo thus resist fatalism. To them, destiny is never a prison; it is an invitation to labor alongside the divine.

2. The Principle of Destiny’s Limit.

At the same time, the Igbo recognize that Chi sets boundaries. A famous saying, “Onye buru chi ya ụzọ, ọ gbagbue onwe ya n'ọsọ”—He who runs ahead of his Chi will exhaust himself in vain, underscores the futility of trying to outrun one’s ordained portion. This is not defeatism but wisdom: it counsels against hubris, reminding individuals that human ambition has limits set by cosmic design. To understand Chi is to understand that each life is inscribed with both potential and boundary.

3. The Principle of Divine Individuality.

Unlike communal deities or ancestral spirits, Chi is strictly personal. No two people share the same Chi. This means that individuality is sacred in Igbo thought. A man may inherit his father’s land, but he does not inherit his father’s Chi. In this way, Igbo metaphysics elevates personal destiny as irreducible and unique. It is a strikingly modern insight in a world often imagined as wholly collectivist.

Chi in Practice

Image Credit: Unsplash

Chi is not merely a lofty abstraction. It is lived. Traditionally, the Igbo maintained shrines to their Chi, often a simple clay figure or symbol placed in a household. In moments of crisis or gratitude, individuals would offer kola nuts, palm wine, or prayers to their Chi. To disregard one’s Chi was to neglect the deepest essence of oneself.

The invocation of Chi also permeates Igbo speech. When someone achieves great success, others remark, “O nwere Chi ọma”—He has a good Chi. Conversely, tragedy might prompt the lament, “Chi ya ejighị ya aka”—His Chi did not favor him. The language reveals how seamlessly the divine self is woven into everyday life, never as something distant but as an intimate companion.

Chi and Morality

Unlike Western notions of the soul, which often tie morality to eternal reward or punishment, Chi does not serve as a judge in the afterlife. Rather, it is concerned with destiny in this world. This does not mean the Igbo lack moral codes—far from it. But morality is mediated by other entities: the gods of justice, the ancestors, the earth goddess Ala. Chi is not moral arbiter but existential partner. Its purpose is not to punish or reward but to guide and co-create.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

This distinction matters because it frames human responsibility differently. To live in alignment with one’s Chi is not merely to be “good,” but to be authentic—to walk the path inscribed for you. Misalignment is experienced less as guilt and more as futility, a sense of working against the grain of one’s existence. The reward for alignment is fulfillment, not salvation.

Tenets of Chi

If one were to summarize the tenets of Chi as a guide to life, they might read something like this:

Every person bears a unique destiny. No two Chi are the same, therefore no two lives are identical.

Human effort is indispensable. Chi does not replace work; it responds to it.

Destiny sets limits. No individual can claim infinite potential; each path is bounded.

Individuality is sacred. To respect another person is to respect the divine uniqueness of their Chi.

Alignment brings peace. To live in harmony with one’s Chi is to live authentically.

Chi in Modern Imagination

Chi continues to resonate far beyond traditional Igbo religion. In the literature of Chinua Achebe, especially Things Fall Apart, Chi is central to the tragic arc of Okonkwo. Achebe deploys the concept not only to explore Igbo cosmology but to dramatize the tension between personal will and fate, a theme as old as Greek tragedy. In contemporary Igbo Christianity, Chi has sometimes been conflated with the Christian guardian angel or even the Holy Spirit, showing how resilient and adaptable the concept remains.

For the Igbo diaspora, Chi also carries psychological and cultural weight. It is a way of naming that inner force that resists assimilation, the reminder that one’s destiny is not fully absorbed by external powers. In this sense, Chi becomes a philosophy of resilience—a way to survive colonialism, displacement, and globalization without losing the core of the self.

Shared Ideas Across Cultures

Image Credit: Unsplash

The idea of a divine self or guiding essence is not unique to the Igbo. Among the Yoruba, the concept of Ẹlẹ́dàá—literally “the creator”—serves a similar role, representing a personal deity tied to one’s head or destiny, often invoked in ritual as ori inu, the inner head. Like Chi, Ẹlẹ́dàá is both personal and divine, a bridge between human striving and cosmic design. Beyond Africa, similar notions appear in Asian traditions.

In Hindu philosophy, the Ātman represents the inner self or soul, believed to be a spark of the divine Brahman, while in Chinese thought the Míng (fate or mandate) operates as a preordained life force that interacts with human action.

These parallels suggest that across cultures, people have wrestled with the same questions: how much of life is chosen, how much is given, and what is the relationship between the human self and the divine order.

Why Chi Matters

Why should the world beyond Igboland care about Chi? Because it offers an alternative to the stark binaries that dominate global philosophy of selfhood: fate versus free will, individuality versus community, God versus man. The Igbo vision refuses such neat separations. It insists that the human self is both autonomous and dependent, both free and bounded, both divine and mundane.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

In an era of existential uncertainty, where individuals grapple with questions of purpose, authenticity, and agency, the philosophy of Chi feels startlingly contemporary. It tells us that life is not a solitary enterprise, nor merely the unfolding of impersonal forces, but a collaboration between the human and the divine.

Conclusion

To understand Chi is to understand the Igbo insistence that the self is never trivial. Each person bears a fragment of the divine, a spark that is both guide and destiny. In this vision, life is not merely about survival or achievement. It is about recognizing and aligning with that inner god-self that walks with you from birth to death.

Perhaps the greatest lesson of Chi is that it dignifies individuality without collapsing into selfishness, and it honors destiny without succumbing to fatalism. It teaches a middle path: to strive, but not arrogantly; to accept limits, but not passively; to recognize in oneself a divine presence that is unique and unrepeatable.

In this, the Igbo offer not just a theology, but a philosophy of being human.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...