The Mirror Isn’t the Villain: Understanding Face Dysmorphia in the Age of Hypervisibility

There was a time when mirrors were silent companions; the reflective surface you looked into before stepping out or maybe after coming in. Today, they follow us everywhere. They are on our phones, laptops, and front-facing cameras.

Every swipe, every post, every Zoom meeting is a reminder that someone, somewhere, often ourselves, is watching. The human face, once an organic part of identity, has become a digital project, a never-ending edit. And in that obsessive scrutiny lives face dysmorphia.

The Culture of Constant Reflection

We live in an era of hypervisibility. It is no longer enough to exist; you must be seen, liked, shared, and reposted. Every day, billions of faces appear on screens, often filtered. The line between what we look like and what we think we look like has blurred to the point of delusion.

Face dysmorphia, clinically tied to Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), is not a new condition, but social media has given it a new stage. It manifests when people perceive flaws that don’t exist or exaggerate minor imperfections until those become all they can see.

For some, it is their nose. For others, their jawline, lips, or skin texture. What was once a passing insecurity now thrives in a system of constant comparison.

Platforms like Instagram and TikTok have turned the front camera into a mirror that never turns off. And unlike the mirror in your bathroom, this one does not just reflect, it judges.

The algorithm rewards symmetry, smoothness, and “aesthetic appeal,” amplifying certain faces while muting others. Slowly, the idea of what counts as “normal” begins to shift, creating a loop of dissatisfaction.

When the Camera Becomes the Mirror

The pandemic years introduced an unexpected side effect: “Zoom face.” Hours spent staring at ourselves during meetings led to a heightened self-awareness that bordered on obsession.

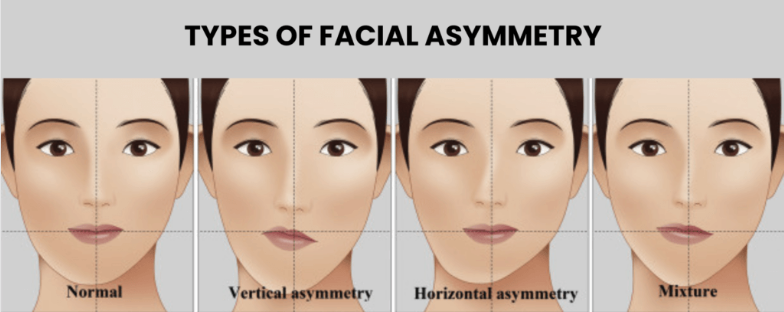

People began noticing asymmetries and angles they had never paid attention to before. Dermatologists reported spikes in cosmetic consultations, not because people were aging faster, but because they were looking at themselves more than ever.

We were not designed to observe our own faces for extended periods. The human brain processes faces, especially our own, in emotionally loaded ways. But the modern world keeps throwing our reflection back at us in high definition. The result is a generation that doesn’t quite trust what they look like.

It is no longer enough to simply be photogenic. Now, you must look good across multiple lenses, lighting conditions, and apps. The selfie is no longer a spontaneous snapshot and we no longer pose not to capture moments.

We apply filters not out of vanity, but out of fear, fear of not measuring up to the curated perfection that floods our screens daily.

The Mirror Isn’t the Villain, Our Culture Is

It is tempting to blame the mirror or the phone camera, but the real issue lies deeper in how we have redefined beauty as something that must be constantly engineered. The beauty standard of this decade is algorithm friendly: clean skin, sharp jawlines, lifted eyes, balanced proportions. It is the same aesthetic replicated across continents, erasing cultural nuances of beauty that once made us distinct.

Social media has democratized attention but standardized beauty. Everyone is now chasing the same “digitally optimized face.” The skin must glow like glass; the nose must be small, straight and pointed; the face must photograph well from every angle.

Even expressions have changed, the subtle pout, the practiced jaw tension, the blank aesthetic of model faces are now part of everyday social media behavior.

This is more about survival in a digital culture that rewards visibility with value. The prettier your posts, the higher your engagement. The more you align with beauty algorithms, the more validation you receive. It is a feedback loop that shapes self-esteem in real-time.

Face dysmorphia thrives here, quietly feeding on likes, filters, and viral beauty routines. It is not that people hate their faces, they just can’t recognize them anymore.

The Role of Filters and Facetune Fetishism

Filters began innocently. A little brightness, a little blur, just enough to “enhance” your photo. But over time, enhancement became reconstruction. Today’s beauty filters can sharpen jawlines, enlarge eyes, narrow noses, and smoothen skin until the result is barely human.

This is what psychologists now call “Snapchat dysmorphia”, the phenomenon where people seek cosmetic procedures to look like their filtered selfies. Plastic surgeons report patients showing them edited pictures and saying, “Make me look like this.” But “this” isn’t real. It is a version of the self that exists only in pixels.

For many young users, this digital beauty is default. Filters are used reflexively, even in casual videos. The more you post, the more you feel the need to maintain the illusion. The mirror shows you one face; the camera shows another; and between those two reflections, your self-image starts to fracture.

The Mental Weight of Always Being Seen

There is an emotional exhaustion that comes from constantly curating how you look. It is the quiet anxiety that follows every front camera activation, the momentary self-check, the instinct to adjust lighting, tilt your head, find your “good side.”

This hyper-awareness is more like control. You begin to micromanage your own existence. Even in offline spaces, people now experience a “camera consciousness”, an awareness that at any point, they could be captured, tagged, or posted.

You are always preparing to be seen, even when no one is looking. Face dysmorphia feeds on that vigilance. The mind keeps cataloging perceived flaws: that pimple, a line, that dent, a dark circle.

You start zooming into your own face in photos, scrutinizing pixels like evidence of imperfection. The irony is most people don’t even notice what you are obsessing about. But the disorder doesn’t care. It convinces you that everyone does.

Relearning How to See Ourselves

Healing from face dysmorphia is not about rejecting beauty, it is about reclaiming ownership of our faces from the digital gaze. The mirror, after all, was never the villain.

It is neutral; it only reflects what stands before it. What distorts the reflection is comparison.

One starting point is to detach self-worth from visibility. Not every face must be posted, not every flaw must be fixed. Real faces move, wrinkle, and shift with time. Real skin has texture, pores, and scars. These are not mistakes; they are humanity in motion.

Social media detoxes help, but awareness helps more. Follow creators who post raw, unedited images. Engage with art that celebrates diversity of appearance. Speak openly about insecurities because silence gives dysmorphia its power.

We must also redefine what “looking good” means. Maybe it is less about symmetry and more about expressiveness. Less about smoothness and more about softness. Less about being flawless and more about being real.

The Future of Faces

As AI-generated avatars and virtual influencers rise, the line between real and synthetic beauty will blur even further. But the rebellion might come from the same generation that started the trend, those who, after years of distortion, are tired of performing perfection.

The future face might not be one that fits a template. It might be one that finally looks like itself, unfiltered, uneven, beautifully human.

Because maybe the mirror is not cruel after all. Maybe it is just waiting for us to look again, this time without fear.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...