South Africa's Legal Earthquake: Black Coffee Ruling Redefines Marriage Equality

South African actress and businesswoman Enhle Mbali Mlotshwa recently secured a landmark legal victory in the Johannesburg High Court. The court declared her customary marriage to music star Nkosinathi “Black Coffee” Maphumulo valid, effectively nullifying their subsequent civil marriage and its accompanying antenuptial contract. This ruling grants Mlotshwa legal entitlement to half of the couple’s substantial estate, underscoring the complex interplay between customary and civil law in South Africa. To appreciate the implications of this case, it is important to understand the concept of customary marriage within the South African legal framework. As legal pluralism specialist Anthony Diala explains, a customary marriage is a union concluded under African customary law, often involving family negotiations, payment of lobolo (bride wealth), and the handing over of the bride to the groom’s family. Extended clans play a vital role, reflecting the traditionally communal nature of indigenous societies.

Under the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 1998 (RCMA), customary unions are legally recognized and are presumed “in community of property” unless expressly excluded by contract. This means that assets and liabilities acquired during the marriage are shared equally upon dissolution. South Africa’s legal system is characterised by multiple overlapping systems. While colonial powers introduced Roman-Dutch and British laws, post-apartheid constitutional reforms gave indigenous laws constitutional recognition, albeit often integrated with Western legal principles. The RCMA itself incorporates elements from the Divorce Act and Matrimonial Property Act, a blending sometimes viewed by cultural purists as alien to traditional customs.

The central dispute in the Mlotshwa–Maphumulo case concerned two marriages: a customary marriage contracted in May 2011 under Zulu custom, followed by a civil marriage in 2017 that included an antenuptial contract. Black Coffee’s argument hinged on the claim that the antenuptial contract excluded the default community of property, thus negating his obligation to share assets. He further contended that the 2017 civil marriage superseded the 2011 customary marriage under RCMA provisions permitting a change of marital regime, so long as court approval is obtained.

Mlotshwa countered that the civil marriage did not legally replace the customary marriage. She argued the antenuptial contract failed to satisfy crucial requirements, namely informed consent and court approval. Section 7(5) of the RCMA and Section 21 of the Matrimonial Property Act require a judge’s approval for any change to a marital property regime in such cases. As a result, she maintained that the customary marriage remained valid and in community of property, entitling her to half the assets accrued since 2011. The court agreed, affirming her claims. This judgment offers clarity and affirmation in South African law. It validates customary marriages and resolves uncertainty around how a later civil marriage interacts with an earlier customary one. Historically, civil weddings were seen to displace customary unions, but the RCMA now prevents such marginalization. The ruling also addresses the phenomenon of “dual” or “double-decker” marriages, where people maintain both a customary and a civil marriage, often due to Christian influence or misconceptions about legal protection. The court effectively declared such practices unnecessary: customary and civil marriages now carry equal validity and default property regimes.

If Black Coffee appeals, his success would likely depend on finding a technical flaw in the High Court’s reasoning. The judgment sends a clear message of equality: all marriages are legally equal in South Africa. Judges now wield the same authority over the division of property in customary marriages as they do in civil ones, eliminating legal disparities. Many hailed the outcome as a win, especially for women married under customary law, who are sometimes vulnerable to being disadvantaged by contracts lacking valid consent or legal oversight. While traditional indigenous norms, emerging in agrarian and patriarchal contexts, often excluded community-of-property regimes and limited women’s individual property rights, this ruling reflects a powerful convergence between customs and liberal statutory reform. It shows that customary systems can evolve to uphold constitutional rights and protect vulnerable spouses equally under the law.

You may also like...

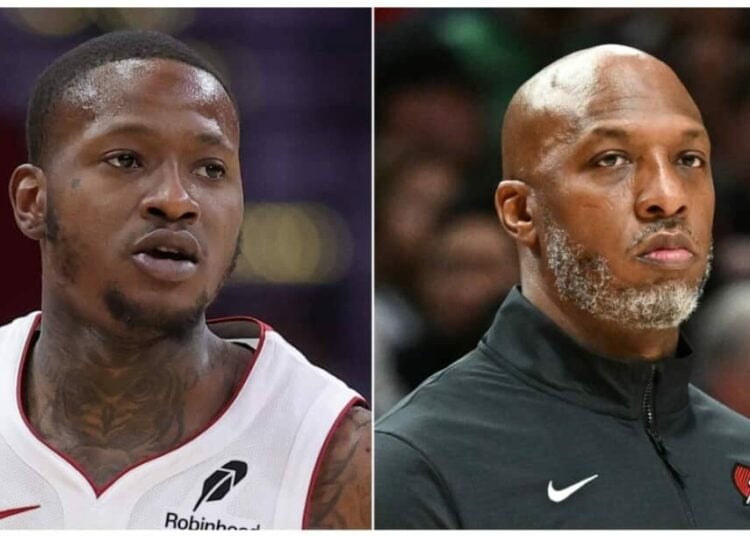

NBA Scandal Rocks League: Billups, Rozier Face Charges in Explosive Sports Betting Probe

Two major federal investigations have rocked the NBA, leading to the indictment and arrest of Portland Trail Blazers coa...

Streaming Wars Intensify: Netflix Exposes Paramount's Role in Industry's 'Brutal Crisis'

Netflix co-CEO Greg Peters has strongly criticized Hollywood's reliance on mergers, arguing they fail to address fundame...

DCU's Epic Future: James Gunn Taps George R. R. Martin's Lore for Major Storylines

James Gunn's DC Universe is heavily influenced by George R.R. Martin's "A Song of Ice and Fire," shaping its structure, ...

K-Pop Firestorm: LE SSERAFIM & J-Hope Unleash 'Spaghetti' Collaboration

LE SSERAFIM has released their new EP, “Spaghetti,” featuring a significant collaboration with BTS’ j-hope, marking his ...

South Africa's Legal Earthquake: Black Coffee Ruling Redefines Marriage Equality

South African actress Enhle Mbali Mlotshwa has won a landmark legal battle, with the Johannesburg High Court validating ...

Groundbreaking! Nigeria Unveils First-Ever Afrobeats Reality Show!

XL Creative Hub introduces "Battle of the Beats Season 1," Nigeria's inaugural Afrobeats production reality show, runnin...

Davido's Diplomatic Daze: Superstar Meets French President Macron!

Nigerian afrobeat superstar Davido recently met with French President Emmanuel Macron in Paris, an event he shared on hi...

Botswana Confronts Wildlife Conflict: Bold New Strategy to Protect Eco-Tourism

Botswana's Minister of Environment and Tourism, Mr Wynter Mmolotsi, announced that addressing human-wildlife conflict is...