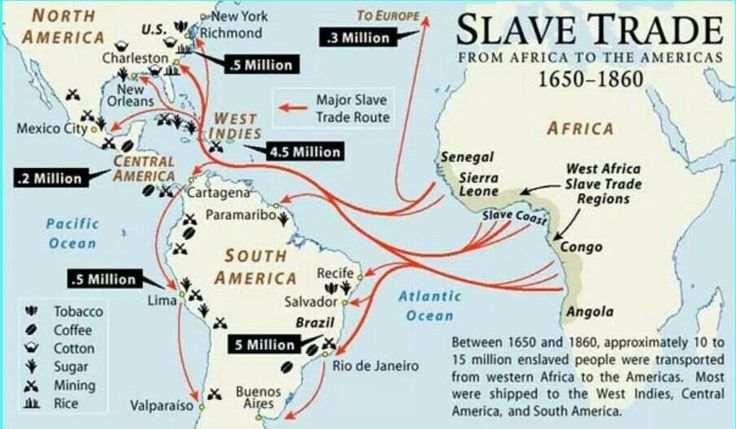

Slave Trade Routes You Never Learned About in School

For many, the history of the transatlantic slave trade is the beginning and end of the conversation about slavery in Africa. In classrooms, it is often painted as a singular tragedy: ships sailing from West Africa to the Americas, carrying millions of enslaved Africans across the infamous Middle Passage. But the reality is far more complex. Across centuries and continents, there existed a web of slave trade routes—overland, coastal, and maritime—that reshaped entire societies. Many of these routes are seldom discussed, hidden beneath dominant historical narratives, yet they are critical to understanding the global dimensions of slavery.

Beyond the Atlantic: The Overlooked Networks

image credit: pinterest

While the Atlantic slave trade captured the most attention due to its sheer scale—over 12 million Africans transported between the 16th and 19th centuries—it was not the only system in operation. TheIndian Ocean slave trade, the Trans-Saharan routes, and internal African networks all played equally transformative, and devastating, roles.

These lesser-known routes operated for centuries before the first Portuguese ships anchored off the West African coast. Some persisted well into the late 19th century, overlapping with colonial expansion and, in some regions, continuing even after official abolition.

The Indian Ocean Slave Trade

From the coasts of modern-day Mozambique, Tanzania, and Kenya, dhows—traditional sailing vessels—carried enslaved Africans across the Indian Ocean to the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, India, and even China. Zanzibar emerged as a notorious hub in the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly under the Sultanate of Oman.

Enslaved people were used as domestic servants, pearl divers, agricultural laborers, and soldiers. Unlike the transatlantic trade, which was driven largely by plantation economies, the Indian Ocean trade was more diverse in its purposes. Yet the conditions were no less brutal: long marches to the coast, dangerous voyages across monsoon-swept seas, and complete erasure of personal and cultural identity.

Historians estimate that between 4–5 million Africans were transported via these eastern maritime routes over several centuries—a number that rivals the Atlantic slave trade in impact but is far less embedded in public memory.

The Trans-Saharan Slave Routes

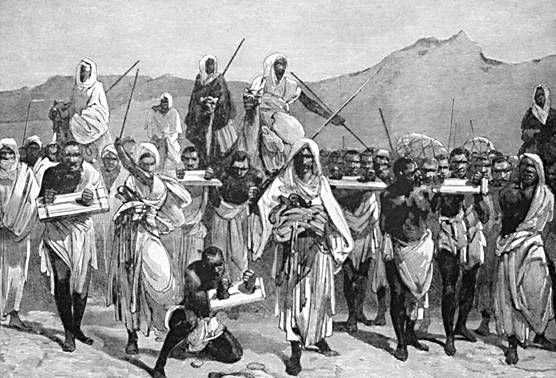

image credit: pinterest

Long before European contact, caravans snaked their way through the Sahara Desert, linking sub-Saharan Africa with North Africa and the Middle East. Enslaved people from the Sahel—regions encompassing modern Niger, Mali, and Chad—were forced to walk thousands of kilometers across blistering desert sands. Many perished along the way from thirst, exhaustion, or abuse.

Upon reaching markets in cities such as Timbuktu, Tripoli, and Cairo, they were sold into households, military service, or as concubines. These trades were deeply tied to the medieval Islamic world’s economic and political systems, making them integral to the prosperity of empires such as the Mamluks of Egypt and the Ottoman Turks.

Internal African Slave Networks

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

While external trade systems are often emphasized, internal African slavery—both pre- and post-European contact—is less openly discussed. Many African kingdoms and empires, such as the Ashanti, Oyo, and Dahomey, maintained systems of servitude before Europeans arrived. However, the arrival of European guns, goods, and ships transformed local enslavement into a massive export industry.

Some internal routes fed into the transatlantic or Indian Ocean systems, while others sustained domestic economies. Enslaved people could be moved between neighboring kingdoms, used in agriculture, mining, or court service, and sometimes integrated into local communities. In certain regions, this blurred the lines between enslavement, bonded labor, and assimilation, making it a complex phenomenon to untangle.

Routes Through the Red Sea

The Red Sea slave trade linked the Horn of Africa—particularly Sudan and Ethiopia—to markets in Yemen, Egypt, and the Arabian Peninsula. Some enslaved people from this route ended up in the armies of Middle Eastern rulers, while others worked in agriculture or served in elite households.

By the 19th century, Sudan became a major source of enslaved people for the Ottoman Empire, especially after Egyptian forces intensified raids into the region. This trade route, though less studied, had enduring effects on the political and demographic makeup of the Horn and parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

Why We Don’t Learn About These Routes

The omission of these histories from mainstream education is not accidental. Colonial powers had a vested interest in simplifying the story of slavery: casting it largely as a European sin exported westward made it easier to sidestep local complicity, eastern markets, and the deeper timeframes involved.

In postcolonial narratives, the focus on the transatlantic trade as the primary story often served political and identity-building purposes. Acknowledging the broader systems—especially those involving African, Arab, and Asian actors—complicates the binary of “oppressor” and “oppressed” that many histories rely on.

Legacies That Still Linger

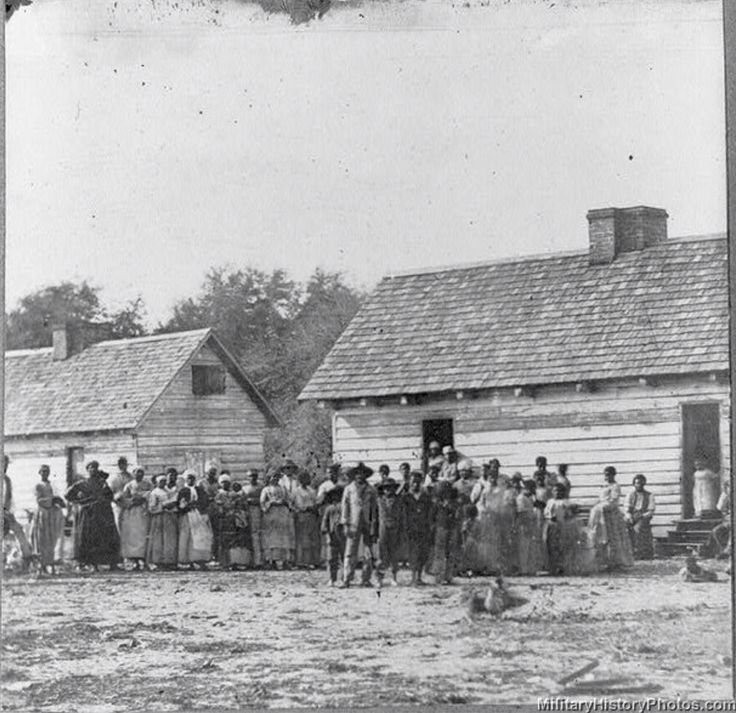

image credit: pinterest

These routes did not just transport bodies—they moved cultures, languages, and traditions, while also erasing many. Populations were displaced, economies restructured, and political alliances shifted in ways that still shape Africa and its diaspora today.

In East Africa, Swahili culture emerged as a blend of African, Arab, and Persian influences—a direct outcome of centuries of Indian Ocean trade. In Sudan and the Sahel, the legacy of the Trans-Saharan trade can still be seen in social hierarchies, ethnic divisions, and cultural practices.

Even more sobering is the way some of these old hierarchies and prejudices persist, influencing present-day conflicts, migration patterns, and the marginalization of certain communities.

Recovering the Forgotten Routes

Historians and archaeologists are now working to uncover and map these lesser-known routes. Oral histories, archival documents in Arabic, Portuguese, and Swahili, and genetic studies are helping to piece together a fuller picture. Museums in Zanzibar, Ghana, and Mali have begun integrating these routes into public exhibitions, challenging the simplified Atlantic narrative.

Recognizing these histories is more than an academic exercise: it forces us to reckon with the global scope of slavery and the shared responsibility for its horrors. It also gives voice to the millions whose stories were erased—not just in the Middle Passage, but in the sands of the Sahara, the winds of the Indian Ocean, and the banks of the Nile.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

In the end, the slave trade was never a single, linear route—it was a sprawling network that touched nearly every corner of the globe. Learning about these forgotten routes is not about diminishing the transatlantic story, but about restoring the full truth. Only then can we understand the enormity of slavery’s legacy—and our shared obligation to remember.

You may also like...

Explosive Racism Claims Rock Football: Ex-Napoli Chief Slams Osimhen's Allegations

Former Napoli sporting director Mauro Meluso has vehemently denied racism accusations made by Victor Osimhen, who claime...

Chelsea Forges Groundbreaking AI Partnership: IFS Becomes Shirt Sponsor!

Chelsea Football Club has secured Artificial Intelligence firm IFS as its new front-of-shirt sponsor for the remainder o...

Oscar Shockwave: Underseen Documentary Stuns With 'Baffling' Nomination!

This year's Academy Awards saw an unexpected turn with the documentary <i>Viva Verdi!</i> receiving a nomination for Bes...

The Batman Sequel Awakens: Robert Pattinson's Long-Awaited Return is On!

Robert Pattinson's take on Batman continues to captivate audiences, building on a rich history of portrayals. After the ...

From Asphalt to Anthems: Atlus's Unlikely Journey to Music Stardom, Inspiring Millions

Singer-songwriter Atlus has swiftly risen from driving semi-trucks to becoming a signed artist with a Platinum single. H...

Heartbreak & Healing: Lil Jon's Emotional Farewell to Son Nathan Shakes the Music World

Crunk music icon Lil Jon is grieving the profound loss of his 27-year-old son, Nathan Smith, known professionally as DJ ...

Directors Vow Bolder, Bigger 'KPop Demon Hunters' Netflix Sequel

Directors Maggie Kang and Chris Appelhans discuss the phenomenal success of Netflix's "KPop Demon Hunters," including it...

From Addiction to Astonishing Health: Couple Sheds 40 Stone After Extreme Diet Change!

South African couple Dawid and Rose-Mari Lombard have achieved a remarkable combined weight loss of 40 stone, transformi...