Colourism in Africa: Are We Still Living in Mental Slavery?

Introduction

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary,colourism is the prejudice or discrimination—especially within a racial or ethnic group—that favors people with lighter skin over those with darker skin. It is the silent weight of inferiority that many individuals feel because of their skin tone, shaping how they relate to others and how society, in turn, perceives them.

This prejudice deeply affects self-esteem and overall social well-being. While some speak openly about it, others silently endure environments where they are ignored, stereotyped, or denied opportunities simply because of the color of their skin. The result is often a sharp and painful divide among people from all walks of life.

Across the globe and particularly within Africa, this subtle yet powerful feeling of colourism has deep historical roots in colonialism and the imposition of Western beauty standards. Colonized peoples were conditioned to view themselves as inferior to their colonial masters, absorbing a distorted sense of self-worth that lingered long after independence.

Over time, Western ideals of beauty, light skin, straight hair, and narrow features further entrenched the notion that lighter is better. Today, these ideals have seeped into the heart of African Gen Z culture, where the pursuit of validation through trends, peer pressure, and the need to “fit in” often overshadows authenticity and cultural pride.

This raises pressing questions: Does external validation now matter more than how we see ourselves? Despite decades of independence and the immense cultural pride that Africa embodies, why does the continent still struggle with the chains of colourism?

Historical Roots of Colourism

Photo credit: Pinterest

The roots of colourism in Africa run deep, stretching back to the colonial encounter when foreign powers imposed not only political control but also cultural and psychological dominance. During colonial rule, lighter-skinned Africans were often favored in administration, trade, and education. Colonial authorities, consciously or not, created a hierarchy where proximity to European features symbolized intelligence, refinement, and power. Those with lighter complexions were sometimes given clerical jobs, educational opportunities, or positions of influence, while their darker-skinned counterparts were relegated to manual labor or denied advancement. This created a system where skin tone was directly tied to privilege.

Missionaries also played a significant role in shaping these perceptions. With their emphasis on “civilized beauty” as aligned with European standards, darker skin was subtly or overtly associated with primitiveness, sin, or a need for salvation. African children in missionary schools were not only taught to read and write but also to internalize Western ideals of beauty, discipline, and culture. The imagery in textbooks, church paintings, and even biblical interpretations reinforced the association of light with purity and dark with negativity.

Over time, these external influences seeped into African social structures, gradually becoming part of family dynamics and cultural perceptions. Lighter-skinned individuals were often viewed as more desirable marriage partners, while darker-skinned relatives sometimes endured silent biases within their own households.

Communities began to equate light skin with upward mobility, modernity, and social acceptance, while darker complexions carried the burden of stereotypes and stigma. This historical conditioning laid the foundation for the widespread colorism we see in African societies today, proof that colonialism did not just redraw borders but also left scars on identity and self-worth.

Modern Manifestations

Colourism is no longer just a colonial relic; it is alive and thriving in contemporary African societies, often disguised as personal choice or “preference.” One of the clearest signs is the booming skin-bleaching industry across the continent.

In countries like Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya, billions are spent annually on skin-lightening creams, pills, and injections, despite repeated health warnings about their dangerous side effects. The industry thrives because it feeds on deep-seated insecurities and sells the illusion that lighter skin equates to beauty, success, and social acceptance.

The media further reinforces these ideals. In Nollywood films, South African soap operas, and Kenyan advertisements, lighter-skinned actors and models are more likely to be cast in lead roles, portrayed as desirable, modern, or aspirational figures. On social media, influencers with fairer complexions often gain more visibility, endorsements, and engagement, subtly shaping public perception of what beauty looks like in Africa. Representation matters, and the lack of balance sends a clear, harmful message.

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

The bias extends beyond entertainment into workplaces and boardrooms. Studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that lighter-skinned individuals are often perceived as more professional, approachable, or trustworthy, creating unfair advantages in hiring and promotions. Such systemic bias reinforces inequality and leaves darker-skinned professionals at a disadvantage, regardless of skill or merit.

Finally, social and marriage pressures remain pervasive. Families and communities sometimes push young men to seek lighter-skinned wives, equating fair skin with higher status or better prospects. Women, in particular, bear the brunt of these expectations, navigating a society that continues to rank beauty and even worth on a sliding scale of complexion.

These modern realities reveal that colorism is not a silent issue. It actively shapes how people see themselves, how they are treated by others, and even the life opportunities they can access.

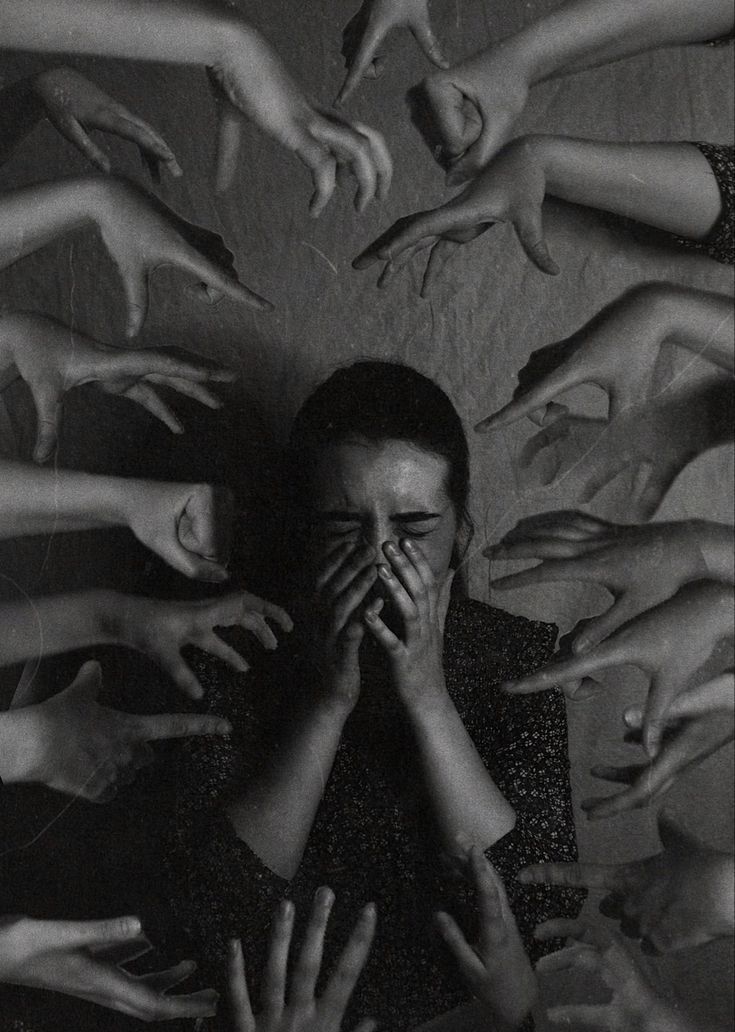

The Psychological Impact

Perhaps the most damaging effect of colorism in Africa is not what it does to the economy or social systems, but what it does to the mind. Colourism plants an internalized inferiority complex that can be traced back to colonial history, where lighter skin was equated with power, privilege, and proximity to whiteness. Generations later, those associations still echo within African societies, shaping how individuals see themselves and others.

Photo credit: Pinterest

For many darker-skinned individuals, the pressure to conform to lighter beauty ideals often translates into self-esteem struggles. Young girls and boys grow up absorbing messages subtly that their natural skin tone is “less desirable,” “less modern,” or even “less human.” This creates a painful reality where identity and worth are constantly measured against unattainable standards, leaving scars that last well into adulthood.

Colourism also fractures communities, creating an “us versus us” divide among people who share the same cultural and historical struggles. Instead of unity, there is competition and comparison—light versus dark, “acceptable” versus “less acceptable.” This internal conflict prevents African societies from addressing larger systemic issues because energy is wasted on self-division.

At its core, the question lingers: Is this not a form of modern mental slavery? Though the chains of colonialism have long been broken politically, colorism continues to chain the African identity psychologically. Until this mindset is dismantled, true liberation both social and personal remains incomplete.

Resistance and Change

Despite the deep scars of colourism, resistance is growing and it is powerful. Across the continent and diaspora, individuals and communities are pushing back against centuries of stigma and reclaiming dark skin as a symbol of pride and strength. Celebrities and cultural icons like Lupita Nyong’o and Khoudia Diop have become global faces of this resistance. By openly celebrating their rich, dark skin on international platforms, they challenge entrenched beauty standards and give millions of Africans a new vision of what beauty looks like. Their presence on runways, movie screens, and magazine covers is more than representation, it’s a revolution.

The cosmetic and fashion industries in Africa are also shifting gears. Local brands are stepping in to create inclusive products that cater to all skin tones, rejecting the bleaching culture pushed by multinational companies. Through marketing campaigns that feature models across the complexion spectrum, they send an important message: beauty in Africa is diverse, authentic, and unapologetic. This cultural pushback signals that while colorism is still alive, the resistance is louder, prouder, and determined to break generational chains of self-doubt. Change may not happen overnight, but each act of defiance builds toward a future where skin tone no longer dictates value.

A Way Forward

Breaking free from colorism requires deliberate effort on multiple fronts. Education and awareness are critical, teaching African history, decolonizing school curricula, and confronting the lingering legacies of colonialism that shaped perceptions of beauty and worth. By understanding where these harmful ideals came from, Africans can begin to dismantle them.

Photo credit: Pinterest

The media also carries a heavy responsibility. Representation matters, and balanced portrayals of all shades in film, television, advertising, and social media are essential in reshaping public consciousness. Every image that uplifts dark-skinned individuals chips away at centuries of bias. On a structural level, policy interventions are needed to curb the harmful skin-bleaching industry, which continues to profit off insecurity and perpetuate dangerous health risks. Governments must enforce stricter bans on toxic bleaching products while encouraging healthier alternatives that celebrate natural skin.

Finally, there must be a collective push to reclaim African beauty standards rooted in authenticity, self-pride, and cultural heritage—not Eurocentric ideals. True beauty is not confined to one shade of skin; it is reflected in the diversity and resilience of African people.

Conclusion

Culture

Read Between the Lines of African Society

Your Gateway to Africa's Untold Cultural Narratives.

Colourism is not merely about personal preference or aesthetics; it is a lingering remnant of mental slavery that continues to divide communities and erode self-worth. The chains may no longer be physical, but they remain psychological, passed down subtly through culture, media, and social expectations.

The challenge before us is clear: Africans must liberate themselves not only politically and economically but also psychologically. Until the mind is freed, the continent will still be haunted by invisible shackles of inferiority and division.

True freedom will come when every shade of African skin is loved, celebrated, and embraced, without hierarchy or shame. Because to love Africa fully is to love it in all its colours.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...