Protecting or Policing? The Implications of Australia’s Under-16 Ban

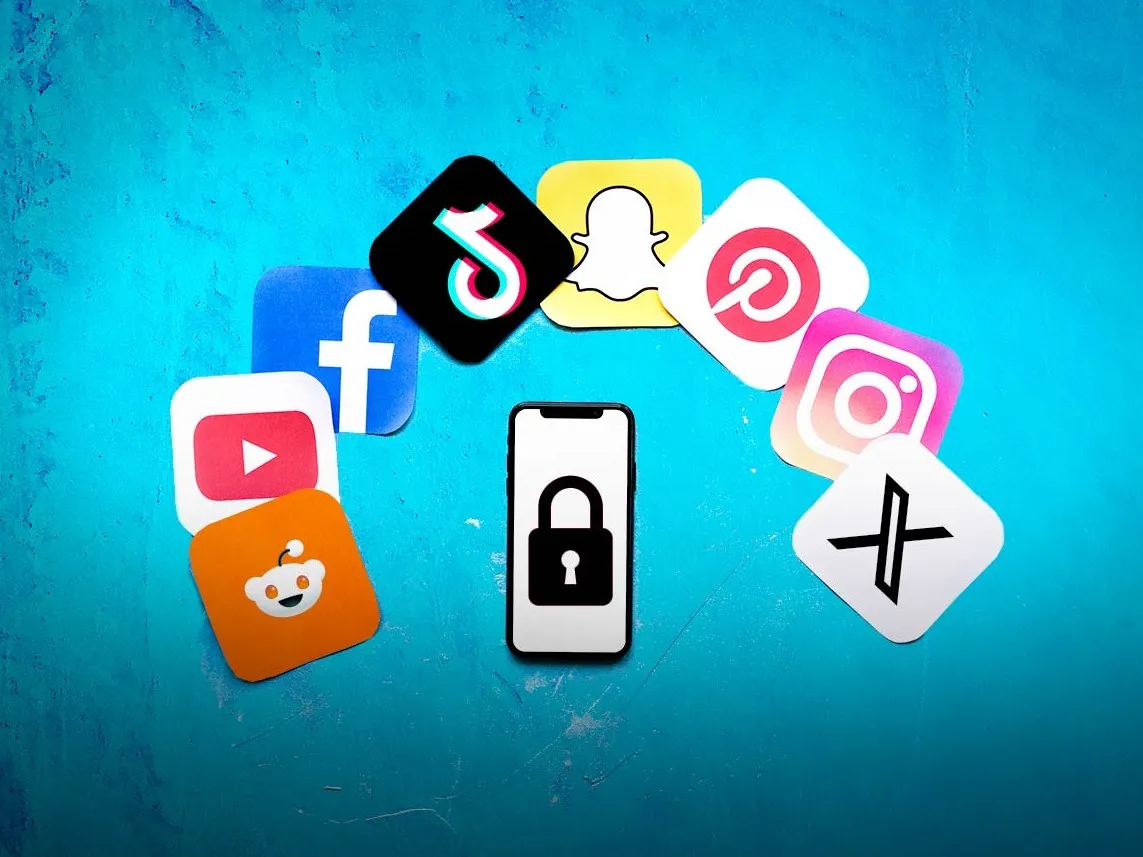

The closing of this year has marked a historic decision: Australia passed a law that makes it the first country in the world to broadly ban access to many social media platforms for anyone under the age of 16.Platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, X (formerly Twitter), YouTube, and several others will be required to block account creation or use by under-16s, or face steep penalties, fines of up to AU$50 million for non-compliance. The law is slated to take effect on December 10, 2025.

This decision has ignited a fierce public debate, from parents who welcome the protection of children, to teenagers and rights groups who see the ban as an overreach, potentially violating rights to expression, community, and access to information. Either way, what Australia has done is more than a regulatory change. It is a bold statement about how a society values childhood, privacy, mental health, and the shape of digital citizenship.

But this begs to ask this question? What this really means for the country, while the ban may come from a genuine desire to protect vulnerable youth, an aspiration many will understand and sympathize with, it raises serious questions about unintended consequences, rights, and whether control is truly the solution or only a new frontier of exclusion.

When Protection Becomes Exclusion: The Risks Behind the Ban

On its face, the logic behind the ban resonates. Studies over the last decade have documented harms associated with extensive social media use among minors: cyberbullying, exposure to inappropriate content, mental health stressors, sleep disturbances, distraction from schoolwork, even the shaping of unrealistic body or social ideals. Australia’s government and advocates of the law argue that banning under-16s from social media is a preemptive strike, a structural protection for childhood.

It’s hard to argue with the desire to preserve innocence, protect young minds, and shield children from the predatory side of a digital world. Many parents support the idea with hope: a world where teens spend more time outdoors, reading books, socializing in real life, learning hands‑on skills, not chasing likes or exposure. For a generation raised digital-first, that vision of reprieve may appear refreshing, a return to simpler childhoods, unfiltered by algorithmic pressure.

But the danger lies in the unintended fallout, and the fact that sweeping bans rarely work exactly as planned. First, exclusion is a blunt instrument. While the law targets minors, the digital environment is less rigid. Teen disconnection from major platforms may push them toward lesser-known, unregulated platforms, underground forums, or VPN‑enabled access to banned apps. These spaces are often less safe, less moderated, more prone to harm and entirely unaccountable.

Also, social media is not only a site of risk, it is a site of expression, identity formation, community building, activism, learning, creativity. For many young people, these platforms offer access to global knowledge, peer support, mental‑health communities, first steps in creative careers, access to information on social issues and political consciousness, or simply a sense of belonging beyond geographical isolation. Banning access risks silencing those voices and denying youth a space to grow socially and intellectually. Indeed, critics warn the move may infringe on basic freedoms, expression, association, access to information.

It is also important to note that there is a serious concern about functionality and fairness. The law mandates social media companies take “reasonable steps” to verify users’ age. That could entail biometric age‑estimation technologies, identity document verification, or inference based on user data. Age‑verification systems remain unproven at global scale, and privacy experts warn they may compromise personal data or require sensitive biometric or identity submission from all users, not just youth.

In effect, what is pitched as a protection for young people may end up imposing sweeping surveillance, eroding digital privacy for everyone. Worse yet, if enforcement is sloppy, legitimate adults could lose access; if enforcement is strict, children might still find ways around it or be pushed into riskier digital corners without protections.

Beyond the practical concerns lies a deeper sociocultural risk: the normalization of exclusion as protection. If we sanitize childhood by removing every potential digital risk, we run the danger of writing off youth voices, agency, and autonomy as collateral damage in pursuit of safety. And history has shown that restrictions meant to protect often entrench inequalities, stigmatize youth, and suppress dissent.

Youth Rights, Expression, and the Illusion of Safety

Perhaps the most compelling challenge against the ban comes from the young people themselves. Two 15‑year-olds, supported by a rights group, have already launched a legal challenge in the High Court, arguing the ban violates the implied constitutional right to political communication, expression, and the ability to engage with society.

Their argument resonates: adolescence is a time of identity formation, of seeking belonging, of building friendships, and increasingly, of civic awareness. Social media in the 21st century is where many young people learn about current events, organise, mobilize, debate, express concerns, and engage with the world beyond their immediate surroundings. To cut them off from those tools could be to cut off a generation’s voice.

Moreover, while the intention behind the ban is child protection, the method treats all under‑16s the same, ignoring context, maturity, parental guidance, and individual readiness. It assumes vulnerability is universal among youth and strength reserved for adults, a sharp simplification of complex lives.

A related concern is that the ban may erode opportunities rather than protect them. Many young people are building skills through content creation (video editing, designs, music, advocacy, community building), skills that often start on social media. Denying them access may limit their creative growth, entrepreneurial potential, and social capital.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Also, implementing this across a free society raises important questions about digital rights, privacy, and consent. If age verification becomes normalized, will social media companies start requiring identity or biometric verification for every user worldwide? Will this further embed surveillance in everyday life under the guise of safety? Will marginalized or vulnerable groups, who may lack easily verifiable ID, be disproportionately excluded?

In short: the ban asks us to choose between safety and freedom, but safety without freedom is often just isolation; and freedom without protection can be harmful. The challenge is not easy, but we should be wary of choosing protection at the cost of dignity, voice, and growth.

Beyond the Ban: What Australia and the World Should Learn

Australia’s social media ban for under‑16s may be unprecedented, but it should not be final. If the goal is truly the wellbeing and healthy development of young people, then policy must be nuanced, flexible, and humane, not blunt and absolute.

It should be noted that any approach adopted should usually combine education, empowerment, and digital literacy, with parental guidance, teaching youth to navigate social media responsibly, understand privacy, recognise exploitation, and self-regulate. The answer should not be outright denial of access, but equipping them with tools to stay safe and informed. Also regulation must respect rights. Age verification should be privacy‑preserving, transparent, and avoid creating permanent surveillance infrastructures. Identity requirements should never become barriers to participation.

The governments, civil society organisations, and platforms should collaborate to create safer, not restricted, digital spaces for all ages. That might involve stronger content moderation, child‑appropriate design, mental health support, and community‑driven safety standards. One important thing to note is that teenagers themselves must be part of the conversation. Laws that affect youth should involve youth voices. Their perspectives, challenges, and ideas matter. Policies should not bury their rights under adult assumptions. Finally, we must acknowledge that social media, for all its flaws, is not an enemy. It is a reflection of our social reality, amplified by technology. It connects people across geographies, enables marginalized voices to be heard, allows for creativity and entrepreneurship, and democratizes access to information. If misused it can be harmful, but if guided it can be transformative.

Australia’s ban is a test case for a world increasingly aware of digital harms. Other countries are watching closely. Some may follow, others may reject it. But what matters is how we respond, whether we build frameworks of empowerment or walls of prohibition.

A ban may silence, but conversation can change minds; regulation may restrict access, but education can open doors.

You may also like...

VAR Mayhem and 'Old Trafford Bonus' Claims: Man United's Win Over Palace Under Scrutiny!

A contentious VAR decision during Manchester United's 2-1 victory over Crystal Palace saw Maxence Lacroix receive a red ...

Osimhen's Post-Win Blast: 'First Besiktas, Then Liverpool!' & Mysterious Man City Nod!

Victor Osimhen showcased exceptional respect towards teammate İlkay Gündoğan by deferring the captain's armband during G...

Reacher Shocker: Popular Series Set for Radical Book Departure After 3 Seasons!

Prime Video's Reacher Season 4, adapting Lee Child's "Gone Tomorrow," is set to feature a record number of fight scenes,...

Scream 7 and Wuthering Heights Shatter Box Office Records Globally!

“Scream 7” has achieved a record-breaking opening weekend at the global box office, driven by strong domestic and intern...

Geopolitical Tremors: Middle East Tensions Drastically Alter Global Flight Paths, African Routes Hit Hardest

Ongoing military escalation in the Middle East is significantly disrupting international aviation, particularly affectin...

GIGX Unleashes Global Payment Power with Strategic Licenses in Zambia and Canada

GIGX Technologies has secured operational licenses in Zambia and Canada for its XPAD product, significantly expanding it...

Airtel's Financial Leap: CBN Grants Full Agency Banking License in Nigeria

The Central Bank of Nigeria has granted Airtel Mobile Commerce Nigeria Ltd a full super-agent license, allowing it to es...

Ripple Unleashes 1 Billion XRP, Market Watches Supply Dynamics

Ripple recently unlocked 1 billion XRP tokens from escrow, a move intended to boost market liquidity and manage its subs...