Opinion: Does Africa Need A New Framework For The Family?

Introduction

We were taught in social studies that the family is the smallest unit of society—our first point of contact with the world, and the foundation upon which every other institution is built. It is within the family that we learn morality, responsibility, gender roles, and how to navigate relationships. It is, quite literally, the bedrock of civilization.

We were also taught that for any social or political system to function—whether it’s democracy, capitalism, or religion—it must be supported by well-defined internal, external, and hierarchical structures. Just as democracy is upheld by courts, elections, and constitutions, every idea or institution needs a system to sustain it.

Which begs a pressing question: what systems were—or are—put in place to support monogamy in Nigeria? And more broadly, in Africa?

Historically, polygamy was not just a marital preference in Africa; it was a deeply rooted social and economic system, reinforced by kinship ties, communal living, and clearly defined roles.

The sudden transition to monogamy, largely brought about by colonial intervention and Christian missionary influence, was not accompanied by adequate structural support. A marriage certificate and wedding is not enough to keep things afloat.

Today, we see the ripple effects: a growing prevalence of absentee fathers, domestic violence, single motherhood, “married single-mothers”, the absence of traditional correcting councils, and the complete lack of legal or policy mechanisms such as child support enforcement. We must ask: did monogamy fail us, or did we fail to build a system to uphold it?

This essay explores the pre-colonial African family structure across different cultures—its values, gender roles, peacekeeping mechanisms, and the systems that sustained it.It also examines how colonialism introduced the benefits of monogamy, but we failed to provide the necessary scaffolding for it to thrive.

Pre-Colonial African Family: The Good, The Bad, and The Fictional.

Chinua Achebe’sThings Fall Apart offers a literary window into the very systems we once had—and how they functioned. Through the life of Okonkwo, the novel presents a pre-colonial Igbo family structure grounded in patriarchy, discipline, and communal oversight.

Okonkwo has three wives and several children, each with roles clearly defined by tradition. His first wife bears children and manages the home, while he shoulders the burden of providing and upholding the family’s honor.

Unfortunately, his violent control over his household, his rejection of his son Nwoye for not fitting masculine ideals, and his devotion to legacy all reflect a culture where male responsibility, however harshly enforced, was not optional—it was a moral and social imperative.

Pre-Colonial Family In the Real World: No Two Societies Are The Same.

Depending on the cultural context, descent and inheritance followed either patrilineal or matrilineal lines, shaping authority and belonging in radically different ways.

Among the Bemba of Northern Zambia, for instance, matrilineal descent meant that a woman’s brothers—not her husband—held significant influence over her children’s future. This inversion of patriarchal norms challenges assumptions about fatherhood and authority, revealing a system in which familial responsibility was widely distributed and deeply embedded in lineage rather than mere biology.

Complementarity Over Hierarchy: Gender Roles and Responsibilities

Gender roles in pre-colonial African societies, while distinct, were not rigidly hierarchical. Instead, they operated on principles of complementarity. Men often undertook responsibilities related to external affairs—such as hunting, warfare, and leadership—while women governed the internal economy: household management, agriculture, childcare, and informal education.

In many societies, women wielded substantial economic and political influence. The Igbo Umuada, for example, was a collective of senior women who could mediate conflicts, enforce moral conduct, and even negotiate ceasefires during war. These women were guardians of social equilibrium, illustrating a nuanced power structure where female authority was institutionalized, respected, and, at times, decisive.

Moreover, older women often held spiritual and moral authority, serving as custodians of tradition and mentors to younger generations. In this sense, age was as important as gender in structuring power.

Systems of Stability: Socialization and Peacekeeping

African family systems were inherently designed for stability. Respect for elders, socialization of children, and gendered labor specialization all played roles in maintaining order and cohesion. Young people were taught early to value communal welfare over individual ambition. Children learned not only their gender roles but also how to resolve conflict, care for others, and contribute meaningfully to collective life.

All That Glitter is Not Gold: Advantages and Disadvantages of Polygamy

Polygamy, particularly in traditional societies, had several practical benefits. It often resulted in larger families, which were advantageous in agrarian economies where more hands meant increased productivity.

Co-wives divided domestic and childcare duties, reducing the burden on each individual. For men, it offered a sense of security, and lineage expansion.

However, polygamy also had significant drawbacks. Jealousy and rivalry among co-wives often caused tension, which undermined marital harmony and affected children’s well-being.

Women experienced emotional distress and psychological strain, particularly where favoritism was common.

Health risks such as STIs were heightened due to multiple sexual partners, and supporting large families could lead to economic hardship.

Children often faced unequal treatment. Male competition could turn violent—especially among younger men who struggled to find partners.

The Advent of Monogamy: Colonialism and the Restructuring of Family

Into this complex and fluid world entered new orders that promoted monogamy and nuclear family structures—largely influenced by Christian missionary ideals and European legal codes. Monogamy was enforced through new institutions: church marriage, civil registries, and legal frameworks.

In fairness, monogamy offers several advantages that contribute to the emotional, social, and economic well-being of individuals, families, and society at large.

One of the most prominent benefits is the deep emotional intimacy and trust that monogamous relationships can foster. With a single, committed partner, individuals should experience a greater sense of security, vulnerability, and mutual understanding, which strengthens companionship and resilience in the face of life’s challenges.

Family stability is another core advantage. Monogamous relationships typically provide a more predictable and cooperative parenting environment, where both partners are emotionally and materially invested in raising their children. This stability reduces the likelihood of conflict and supports better outcomes in child development and education.

Alongside emotional and familial stability, monogamy also brings economic benefits. By concentrating resources within a single household, couples can better manage finances, improve their standard of living, and build a more secure future for their children.

Health considerations also support monogamy. Exclusive partnerships help limit exposure to sexually transmitted infections (STIs), promoting better physical health for both partners. Additionally, monogamous marriages often enjoy legal and social recognition, which grants couples inheritance rights, legal protections, and societal acceptance—factors that reinforce long-term commitment and stability.

Children raised in monogamous families often benefit from improved welfare outcomes. These households typically have lower rates of neglect, abuse, and accidental death, owing to smaller family sizes and more concentrated parental attention.

In terms of economic development, monogamy can encourage men to channel their resources into productive activities rather than maintaining multiple households, which boosts economic output and contributes to national growth—particularly in regions where polygyny was once widespread.

Why Polygamy Can no longer work in Africa

By now, you might be thinking: Then let’s return to polygamy. But the truth is, the systems that once upheld polygamy no longer exist either.Virtually no one is hunting in the bush for food. Men and women do the same jobs, they take the same risks to survive. Our fences now rise twelve feet high, a far cry from the days when communities lived with open courtyards and shared lives. The elder who once “saw things while sitting down” must now climb an iroko tree just to glimpse the chaos in his neighbor’s compound. Our architecture has changed, our built environment has changed—there is no longer a town square, no elders’ forum, no fire around which information is passed, or hunters celebrated. Our jobs have changed, our schedules have changed, and perhaps most profoundly, our desires have changed. This is not a bad thing.

The past, no matter how rich in wisdom, is not the path forward for the Africa of today. And the present systems are equally failing to offer a sustainable alternative. We are caught between two broken models, and the urgent task before us is not to return or to remain, but to reimagine: to build new systems that reflect who we are now, and who we hope to become.

So tell us your thoughts in the comment section, what frameworks can we put in place to secure the future of the African family?

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

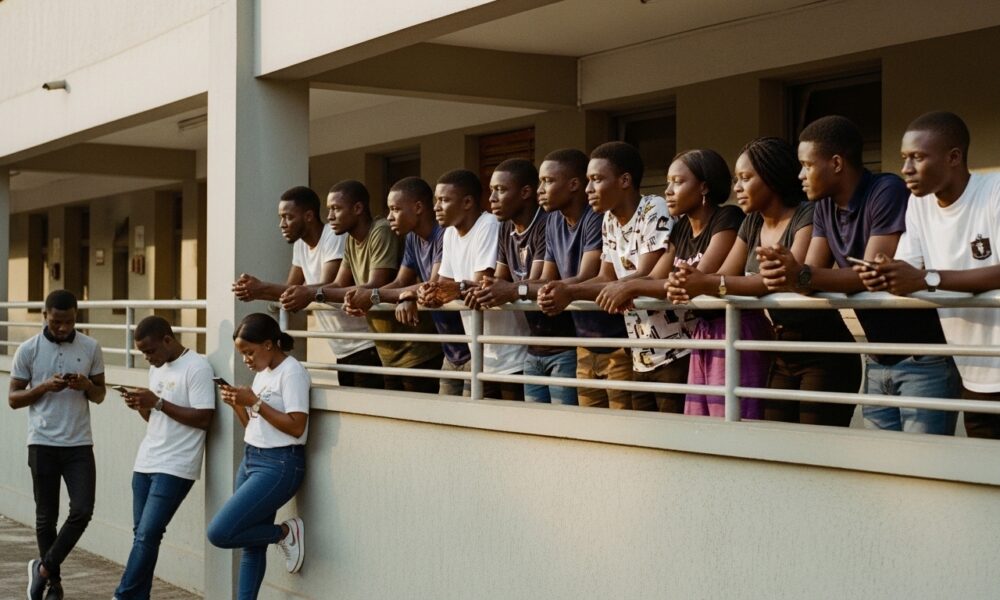

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...