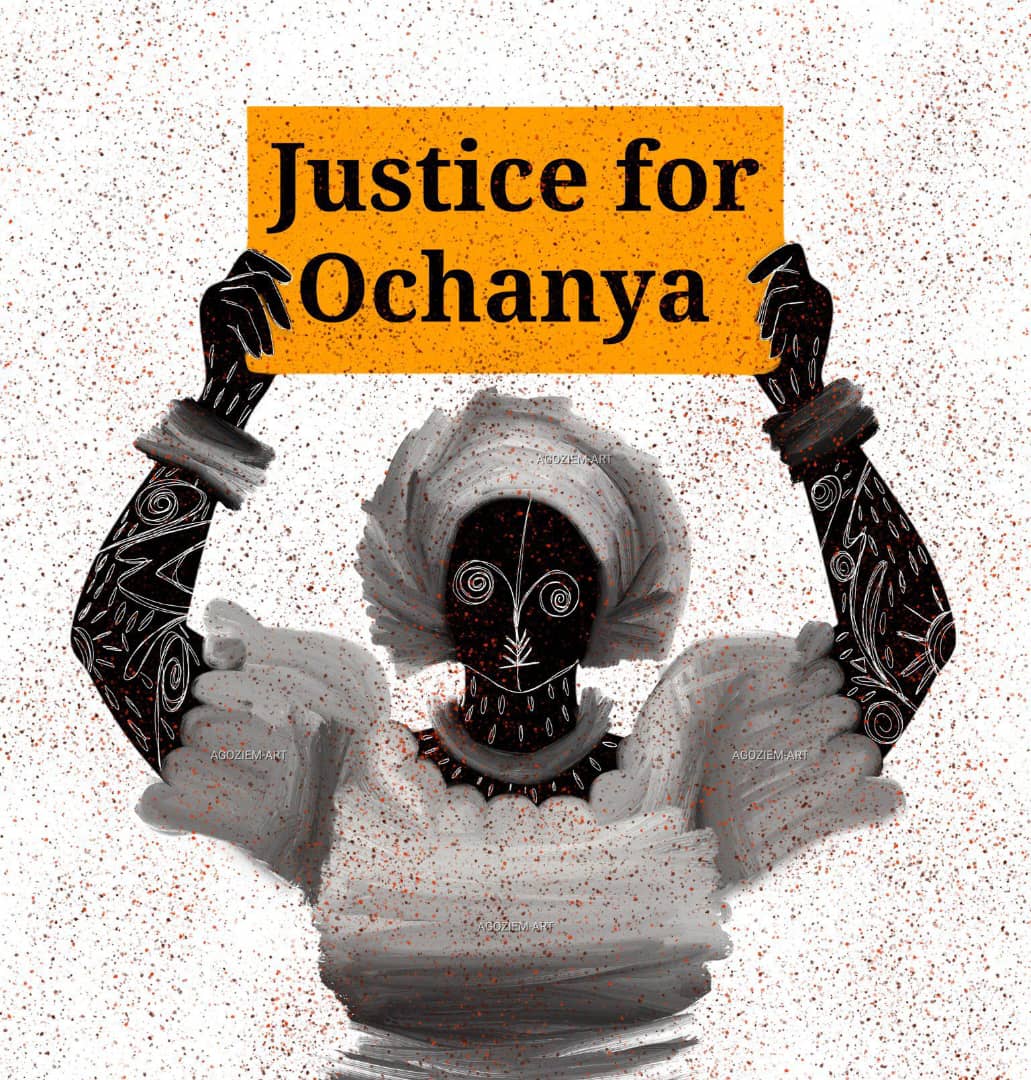

Justice for Ochanya? What Does the Law Say

Introduction

Maybe justice in this country has a bedtime. Maybe it clocks out at 10pm and wakes up only for dinners with diplomats. Because every time a little voice or the average man cries for help, the law seems to be somewhere between a nap and a long vacation. I say this as someone who is seeing the outburst caused by the smallness of a name — Ochanya — and how the country is currently raging and calling for justice to be met. I am tired. I am furious. And I refuse to be polite about it.

Ochanya was thirteen when she died. Thirteen for crying out loud!. A child entrusted to an aunt’s household for the sake of schooling, why? Because her community had no schools, why would a community have no school in the first place, where is the government for that?. She was supposed to be a niece who should have been mothered, protected, and taught how to tie her uniform properly, not taught to hide wounds or swallow shame. Instead she was betrayed by adults whose very job description included care: a guardian and his son. The abuse, we now know, was not a single crime of opportunity but a long-running, monstrous theft of childhood — repeated sexual violations that lasted for years. Reports say the abuse continued over something like five years, until Ochanya’s body and spirit could take no more, she died of vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) and other health related diseases. The men accused? People who are still moving in the corridors of respectability: a lecturer and his son. The tragedy here is not only what was done to her body; it is how the institutions, family, school, law failed her at every turn.

So I ask again: Who actually does that to a child, what is sexually attractive about an 8 years old child and the fact that it continued until her death.

Who commodifies the ribs and laughter of a child and calls it desire? The question is rhetorical because we don’t want to look at what predators are forced to reveal, their own depravity, so we invent reasons to blame the child instead. This is the first violence: we teach ourselves that girls are responsible for crimes committed against them. This is the second: we dress our criminal justice system in costumes of protection while it hides the keys to the courtroom in the pockets of the powerful.

What Does The Law Say

On paper, Nigeria has laws that should terrify predators. The Child Rights Act (2003) declares the best interest of the child as paramount and promises protection from sexual exploitation, abuse, and neglect. The Criminal Code criminalizes rape, defilement, and related offenses, and in many sections prescribes severe penalties for sexual crimes against minors. Beautiful words. Powerful intentions. Documents to print and pin above office desks and forget. The question is not whether the laws exist; the question is whether they are enforced with the urgency and moral imagination these laws demand.

So why did Ochanya’s case stall? Why did the wheels of justice behave like a car with a flat, very visible, very loud, but unable to move forward? The judge in the first proceedings reportedly dismissed the case for lack of substantial evidence. The legal technicality is a blunt instrument: evidence must meet certain thresholds in court, and when witnesses are silenced, intimidated, or simply forgotten, “insufficient evidence” becomes the path for impunity. I am not interested in legalese as an escape route. If proof evaporates because those responsible have money, status, or simply the patience to out-wait outrage, then the law has become a loophole machine. The law can protect only if investigating institutions are proactive, forensic processes are robust, and the judiciary understands that children cannot testify like adults or endure the same trauma of cross-examination without special care.

Let’s talk about how we talk about rape in this country. Ask any woman who has testified, and she will tell you the ritual: before the judge asks “Did it happen?” individuals have often quietly asked in whispers “What was the guilty wearing?” as if a child could invent a script for her own murder and stage it for attention. That is the gendered alchemy at work: transform every victim into an accused accomplice by insinuation. “Why didn’t she speak earlier?” becomes shorthand for blame; “maybe she encouraged it” becomes common sense; “children sometimes lie” becomes an excuse. And our humor? We smirk at the absurdity of it while normalizing the necessity that girls learn silence as survival training.

Sarcasm and adaptability to rubbish helps us cope, but it also reveals hypocrisy. Apparently, the only thing Nigerians doubt faster than an election result is a woman’s rape story. Meanwhile, when a man is accused, the default script is “presumption of innocence” — noble and necessary in principle, maybe she might have wanted it too, you say what? Because in practice, innocence is often weaponized when the accused is a provider, a professor, or a notable figure whose social integrity is at stake. The scales of sympathy tip depending on whose bank account trembles.

Also is it not possible, I wonder aloud, if men can be victims too? Of course they can. But when we map the harms of sexual violence in our society, women and girls are disproportionately targeted because patriarchy weaponizes power against the weak. Our conversation must hold both truths: men can be raped, and the systemic patterns overwhelmingly victimize girls. Yet our public imagination rushes to protect accused men’s reputations while letting children collect the shards.

Justice Delayed – The Myth of Closure

There is a quiet form of violence here: time. Justice delayed is not justice served and eventually can become justice denied; it is a slow erasure. Cases are docketed, adjourned, adjourned again, witnesses change addresses, witnesses get tired, witnesses are offered hush money; memories get fuzzy; files get “misplaced.” And social outrage, that combustible force, burns hot on social media for days and then the timeline moves on. If it weren’t for activists and the recent renewed agitation on social platforms, Ochanya’s files might have collected only dust. The reopened interest, the calls to “JusticeForOchanya” that resurfaced seven years later on social media platforms including X formerly called twitter, are a testimony to how public pressure can prod a sleepy system. But it should not require a trending hashtag to reopen a case that involves a child’s death. That is a shame on the state.

And yes, for balance and complexity, let us not pretend the system is never wrong in the other direction. I have seen how lives are upended by false accusations, how the machinery of suspicion can maul reputations and livelihoods when the facts are not thoroughly investigated. Justice delayed also becomes the weapon of suspicion. In the heat of an emotional campaign, the danger is that the pendulum swings too far, from protecting victims to presuming guilt without proof. The law must be careful, rigorous, and humane: it must protect the innocent and punish the guilty, but how then can we draw the line?. Usually the former is the ideal, but the reality is messier, and that mess is where children fall through – the matter just get as e be sha.

So what does the law actually allow? The Child Rights Act, which, full disclosure, is not yet domesticated in every Nigerian state , sets out protections and procedures meant to centre the child’s best interest. Twenty-four of thirty-six states have adopted versions, but that means a child’s rights still depend too much on geography. Meanwhile, the Criminal Code contains provisions on rape and defilement that impose severe penalties, and reform attempts have sought to remove statute-of-limitations loopholes and increase punishments for sexual crimes. Legally speaking, the architecture for accountability exists; administratively and culturally, the foundation is rotten. Having a law on paper and making it work at the grassroots are two different tasks.There is a special cruelty in the way our courts treat children. A child who testifies faces interrogation designed for adult endurance; she is cross-examined on private details in public; she is asked to relive trauma without adequate psychological support. The Child Rights Act demands child-friendly procedures, but how often do we actually see that? Protective provisions that sound humane in committee rooms are often reduced to advisory notes in practice. If the law is to mean anything, then child victims and any other victim of any age must be treated with dignity, in interviewing, in evidence-gathering, and in court. Special courts, trained magistrates, forensic teams, child psychologists, these are not optional extras. They are the tools that separate a functioning justice system from a system that merely imagines itself to be just.

There is also a cultural problem that the law alone cannot fix: patriarchy. When men are taught to “man up” and keep shame inside, victims, male or female, are less likely to report. When communities prioritize reputation over safety, children become easier to hide. When influential people are involved, the usual story plays out: denials, delays, a carefully curated narrative of innocence. That is why social movements matter. They name what the law fears to name; they force public institutions to act when institutional inertia would rather protect its own. Public outrage isn’t perfect, but it is often the oxygen that prevents a case from being buried.

And we must always remember: laws change, but survivors live with aftermaths. They live with bodies that remember. They live with medical complications, with interrupted schooling, with stigmas and whispers. Ochanya’s death was a failure on many levels, a failure of a family that should have protected her, a failure of a school that entrusted her to dangerous hands, a failure of investigators who could not translate anguish into admissible evidence quickly enough, a failure of the government for not providing school facilities and a failure of a society that prefers polite silence to messy accountability. We can debate technicalities until the cows come home, but no argument about procedure will bring back a child.

So what do we demand? Full, uncompromised investigations whenever a child is alleged to be abused. No shortcuts, no convenient dismissal. There should be fast-tracked, child-sensitive judicial processes that recognize children’s limited ability to withstand traditional cross-examination. Health care and facilities should have better forensic resources: medical exams must be timely, documented, and preserved. The laws must be domesticated uniformly across states so that a child’s safety isn’t subject to where she lives. Capacity-building for police, prosecutors, and judges on handling sexual offences against minors, training that is not theoretical but practical. And finally, society must change the conversation away from blaming victims toward dismantling systems that enable abuse.

Conclusion – My Cry for Ochanya

I am not calling for lynch mobs. I am calling for functioning institutions. I am asking for legal courage, for prosecutors willing to pursue powerful suspects, for judges who will look beyond status and money. I want families to be accountable and communities to protect children, not reputations. I want schools to be sanctuaries, not hunting grounds. Above all, I want Ochanya’s name to be more than a headline in the history of Nigeria trends and news. I want it to be a measure: how we treat this case will tell us how we treat every other child who is vulnerable.

To those who would say, “But we must protect the rights of the accused,” I agree. Due process is a cornerstone of law. But due process must not be an umbrella under which predators hide. The scales of justice cannot be so elastic that they straighten only when the accused is poor or unpopular. The law’s job is to balance rights, the right of a victim to be heard, to be protected, to receive redress, and the right of the accused to a fair hearing. We must build systems that respect both without silencing the child.

I write this because I've noticed that silence is where I fear we are most complicit. We should not be polite about the parts of our country using cute slogans to paint scenarios that require deep structural change. We should not tolerate euphemisms for murder, for when a child dies because adults delayed justice, that is a kind of communal homicide. Call it what it is: negligence, corruption, cowardice. Call it finally by its name so we can begin the work of repair.

Ochanya’s grave will not speak; her name must be heard and we are the voices that make the name to be heard. Let us speak for her with courage, not performative sorrow. Let the law be enforced, not read. Let the courts be instruments of protection, not venues for rehearsed denials. And let every parent, teacher, and neighbor take an oath: never again will we choose convenience over a child’s life.

Justice for Ochanya is not a request; it is a demand. The law says many things on paper, now it must act in practice. If we care about the next child, we will make sure this is the moment when promises stop being paper and start being action. I am angry. I am grieving. And I will not let her name fade into the fatigue of tomorrow, because when it come to rape cases, we should do less talking and actually start taking actions, make dem show all the rapist better pepper, because the tolls it has on the innocent can not be over emphasized, and finally nor let anybody call your kid or sister our wife, she is not of marriageable age and there is nothing appealing to make her anyones wife, make dem go front.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...