From Ajo to Hustle Culture: How Informal Saving Habits Shaped Money Mindset.

Before savings accounts became common, before fintech apps introduced digital “safe locks,” before mutual funds and stock-buying became the language of modern personal finance, Africans had already built their own sophisticated economic systems, informal, yes, but incredibly effective. These systems were rooted in culture, community trust, and the instinct for survival in unstable economies.

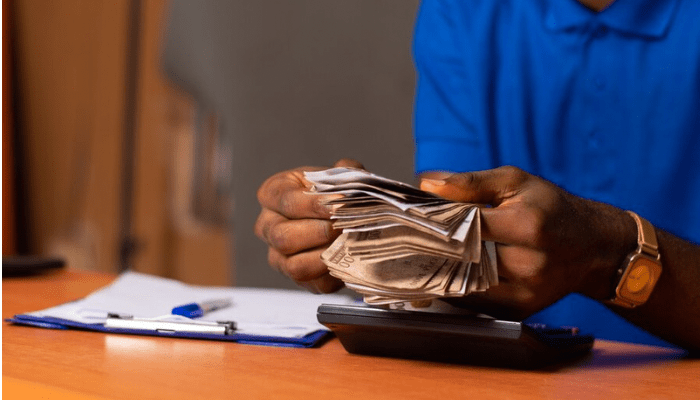

If you grew up in an African household, you probably witnessed scenes that now feel nostalgic: mothers keeping money in carefully labeled envelopes tucked inside wrappers or wardrobe corners to be given to the money collector for saving; fathers waking up before dawn to hustle to ensure that there was an extra naira to be counted; aunties in the neighborhood writing names in contribution books with the precision of accountants; market women gathering weekly to contribute to a financial group they formed; an entire neighborhoods relying on rotational savings as their financial safety net. These practices weren’t just old-fashioned; they formed the backbone of financial stability long before banks became accessible.

Today, the shift is clear. The younger generation are saving through fintech apps, automated deductions, digital platforms, and investment wallets. Yet many of these young savers were raised in households where the concept of ajo was the default system for years. And in many low-income communities across Africa, this system still thrives and is yielding impact for those who still believe in it.

This raises an important question: How did these old methods of saving shape the financial behavior, discipline, and economic resilience we see across generations today?

The Cultural Roots of Ajo and the Hustle Culture

Ajo, known by different names like esusu in Nigeria, susu in Ghana, chama in Kenya, or table banking in Uganda, did not emerge from convenience. It emerged because people had no other choice and for many that could not access financial services from banks it gave liberty to them and helped the unbanked, with figures showing that over 350 million africans being completely unbanked. Not to mention the fact that many of these africans especially women did not fully understand how to use financial services, with either formal banks being too rigid, too strict, or simply uninterested in serving the average market woman or low-income earner. So many Africans built what many researchers and the financial world now recognizes as one of the most efficient informal banking structures.

These savings groups were communal at their core. Market women collected contributions weekly, unions enforced accountability, cooperatives helped families survive during tough times, and everyone involved understood that trust was the true currency. No collateral. No paperwork. Just the strength of your word, your personal integrity and the reputation of your family.

Women were the unofficial bankers of their communities. They knew who could be trusted, who needed help, and who had defaulted in the past. In many ways, they ran microfinance long before any international NGO used the term.

But this culture also engraved something deeper in our psychology: the hustle mentality. Many African parents grew up in economies where inflation was unpredictable, currencies fluctuated without warning, and government support was unreliable at best. They internalized the belief that if you didn’t save aggressively, hunger could strike at any moment. The common reminder, “If you don’t save, hunger will humble you,” was not just advice but a reflection of lived experiences.

This shaped a generation that learned to avoid borrowing, to depend heavily on self-reliance, to prepare for emergencies even when things seemed stable, and to see financial discipline even when they did not understand all the financial terms we know today as the foundation of dignity.

How Ajo Actually Works and the Emotional Costs Beneath It

Although the concept of ajo appears simple, its operation is a remarkable display of structure, discipline, and communal trust. A group of people agree to contribute a fixed amount at regular intervals. Each member receives the collective sum during their designated turn. There is no formal contract, yet the accountability is stronger than in most modern financial institutions. If you default, you don’t just disappoint yourself, you damage your reputation within the entire community.

Small traders have used ajo to raise capital for decades. Families relied on it to pay school fees, rent, hospital bills, or respond to emergencies. Communities used it to fund weddings, funerals, and business expansions. It became a type of shadow banking system that banks still struggle to replicate because the system’s strength was cultural, not financial.

But beneath its effectiveness are emotional pressures that many people carried for years without naming. Saving became fear-driven. Spending became guilt-driven. Rest became a luxury. And enjoyment often felt like a sign of irresponsibility. Many people grew up with a money scarcity mindset, believing that financial safety only came through relentless hustle and constant sacrifice. The idea of financial rest, which today’s digital generation often pursues, felt almost irresponsible.

Contribution groups also faced challenges: members disappearing with the collective funds, people defaulting on their turn, or internal disputes that collapsed entire groups. There was also the problem of inflation; money saved manually lost value quickly, especially in countries with unstable currencies. Yet despite the flaws, the cultural value overshadowed the risks because it was a system that worked for people who had no alternatives.

How Money Behaviors Differ Across Generations

Ajo didn’t just influence spending habits; it shaped entire generational identities.

African fathers, for example, carried the weight of extreme responsibility. Their financial decisions were anchored in duty, securing land, paying school fees, providing food, and preparing for emergencies. Many of them worked without breaks, saved quietly, and often kept financial pains hidden because the role of “man of the house” came with silent sacrifices. Financial vulnerability was not an option.

African mothers, on the other hand, became the financial officers of the home. They ran the envelope system long before budgeting apps existed. They kept contributions, saved extra money behind the scenes, stockpiled food to stretch household income, and made sacrifices that held families together. Their financial intelligence was practical, tactical, and absolutely essential.

Well the kids growing up and young ones were excluded from financial decisions and matters, it just dawned on them as they grew up that it was time to start contributing to household expenses or saving, no prior teaching or financial education of any sort. But Gen Z today lives in a different world. Gen Z these days rely on digital savings apps, automated deductions, investment wallets, and side hustles. The concept of savings these days is for financial freedom; chasing soft life ideals and experiences, convenience, and mental-health-centered financial decisions, but in all of these, they live with higher economic anxiety than the Millennials and their parents due to the rising cost of living. Their financial behavior is a blend of ambition and fear, shaped by a globalized world that constantly compares lifestyles online.

These differences explain why older generations prioritize survival while younger people balance survival with lifestyle, identity, and mental well-being. Both approaches are valid, but deeply shaped by the systems they come from.

The Social Pressure and Economic Impact of Ajo

One of the least discussed aspects of ajo is the social pressure embedded within it. Defaulting on your turn was not just an inconvenience, it could bring shame to you and your entire family. There was a deep need to belong to the group, to be seen as responsible, and to maintain dignity. These pressures shaped a culture where discipline was non-negotiable and where economic contributions became a measure of social integrity.

On a broader scale, ajo strengthened entire microeconomies. Marketplaces thrived because collective savings increased purchasing power. Money circulated faster because contributions created financial momentum. Many households relied less on banks, and many small businesses found easier access to capital. Women became financially empowered as informal bankers, reinforcing their economic influence within communities.

In essence, ajo didn’t just help people save; it helped communities survive, grow, and stay resilient during times of uncertainty.

The Future: Blending Traditional Systems With Modern Financial Technology

Today, Africa is witnessing a fascinating evolution. Fintech companies like Piggyvest are modernizing the spirit of ajo through digital platforms that combine transparency, automation, and security. Digital thrift groups mimic the rotational savings system. Cooperative digital banking allows communal investments. Fintech apps make saving easier, more accountable, and more accessible to young people who may not have the same patience for manual methods.

Still, the essence remains the same: trust, community, survival, and solidarity. Technology isn’t replacing tradition; it is upgrading it. Ajo is not dying, it is literally evolving.

At its heart, ajo was never just about money. It was about connection. Trust. Shared responsibility. Economic identity. It shaped the hustle culture that many young Africans now critique but also inherit.

Hustle culture, with all its flaws, is a product of generations who survived unstable economies through discipline, sacrifice, and communal support. Today’s digital generation is rewriting that story with new tools, new perspectives, and new priorities.

But the question remains: As Africa’s financial systems continue to modernize, will digital banking truly replace the trust-based systems that held communities together for centuries or will the two continue to merge, shaping a hybrid future of finance?

You may also like...

If Gender Is a Social Construct, Who Built It And Why Are We Still Living Inside It?

If gender is a social construct, who built it—and why does it still shape our lives? This deep dive explores power, colo...

Be Honest: Are You Actually Funny or Just Loud? Find Your Humour Type

Are you actually funny or just loud? Discover your humour type—from sarcastic to accidental comedian—and learn how your ...

Ndidi's Besiktas Revelation: Why He Chose Turkey Over Man Utd Dreams

Super Eagles midfielder Wilfred Ndidi explained his decision to join Besiktas, citing the club's appealing project, stro...

Tom Hardy Returns! Venom Roars Back to the Big Screen in New Movie!

Two years after its last cinematic outing, Venom is set to return in an animated feature film from Sony Pictures Animati...

Marvel Shakes Up Spider-Verse with Nicolas Cage's Groundbreaking New Series!

Nicolas Cage is set to star as Ben Reilly in the upcoming live-action 'Spider-Noir' series on Prime Video, moving beyond...

Bad Bunny's 'DtMF' Dominates Hot 100 with Chart-Topping Power!

A recent 'Ask Billboard' mailbag delves into Hot 100 chart specifics, featuring Bad Bunny's "DtMF" and Ella Langley's "C...

Shakira Stuns Mexico City with Massive Free Concert Announcement!

Shakira is set to conclude her historic Mexican tour trek with a free concert at Mexico City's iconic Zócalo on March 1,...

Glen Powell Reveals His Unexpected Favorite Christopher Nolan Film

A24's dark comedy "How to Make a Killing" is hitting theaters, starring Glen Powell, Topher Grace, and Jessica Henwick. ...