BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 2447 (2025) Cite this article

Physical health is the overall well-being of the body, ensuring the proper functioning of organs, muscles, and systems. It includes fitness, nutrition, disease prevention, and healthy lifestyle choices. This study investigates the physical health development of children in Bangladesh and identifies key influencing factors. The data of this study was collected through a two-stage sampling approach, with trained interviewers administering structured questionnaires. A total of 401 children aged 6 to 10 years were included in the analysis. To examine the associations between variables, the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were conducted for bivariate analysis, while a generalized log-normal regression model was employed to assess the impact of various socioeconomic and demographic factors on children’s physical health development. The findings indicate that early childhood diseases negatively affect physical development (OR: 0.95, CI: 0.92–1.83, p < 0.05). Conversely, access to outdoor play opportunities (OR: 0.96, CI: 0.93–0.99, p < 0.05) and the provision of supplementary food (OR: 1.05, CI: 1.02–1.09, p < 0.05) significantly enhance children’s physical health. Additionally, gender (OR: 0.96, CI: 0.94–0.99, p < 0.05), regional division (OR: 1.04, CI: 0.98–1.07, p < 0.05), and monthly family income (OR: 0.92, CI: 0.98–1.09, p < 0.05) were identified as significant determinants of physical health outcomes. These findings underscore the need for targeted public health interventions to promote children’s physical well-being in Bangladesh. Policymakers should prioritize strategies that mitigate the effects of early childhood diseases, enhance access to outdoor activities, and ensure adequate nutritional support to foster improved health outcomes among children.

Child physical health refers to physical well-being, including their ability to manage challenges, build relationships, and cope with stress, which lays the foundation for future health outcomes and emotional resilience [1]. It can be defined as a state in which all body systems function properly, ensuring optimal growth and development [2]. However, Child health development is a dynamic process influenced by various factors, including, behavioural, cognitive, personality, and emotional growth [3]. The first five years of life are particularly critical, as a child’s brain develops by 90% during this period [4].

Globally, child physical health remains a significant concern. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) prioritize childhood development, with Target 4.2 aiming to ensure access to quality care and education by 2030. Childhood development is essential for achieving at least seven SDGs addressing poverty, hunger, child mortality, health, gender equality, water, sanitation, and inequality [5]. Strengthening these areas is vital for improving child physical health and well-being. According to the World Bank (March 2021), over 40% of children below primary school age worldwide require childcare but do not have access to it. Between 2010 and 2016, 25.3% of children in 63 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) experienced developmental deficits, with South Asia reporting a 32.6% prevalence [6]. Additionally, a study by Islam et al. (2021) indicated that in developing countries, approximately 200 million children during the first five years are at risk of developmental delays [7].

In Bangladesh, socioeconomic and cultural factors significantly influence a child’s physical health, including parental education, income levels, housing conditions, healthcare access, and traditional practices [8, 9]. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Social Determinants of Health framework highlights how economic, social, and environmental conditions shape health outcomes [10]. Findings from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) highlight concerning trends. In 2012, 70% of children were developmentally on track. However, the MICS 2019 showed that 25.26% of children were not meeting early childhood development milestones, indicating ongoing challenges in child physical health development [11, 12]. Bangladesh ranks among the top ten nations with the highest number of underprivileged children who face severe risks, including cognitive, physical, social, and emotional impairments [7]. Factors such as poverty, malnutrition, and limited healthcare facilities continue to hinder child physical health development in the country.

Early childhood development (ECD) is closely linked to physical health. According to Hasan et al., (2023), inadequate cognitive and socio-emotional growth can lead to physical and mental health problems [12]. F. Reiss (2013) identified parental socioeconomic status (SES) as the most significant determinant of a child’s physical health. Children from low-income families often face higher rates of malnutrition, limited access to quality healthcare, and unhygienic living conditions [13]. Urban-rural disparities also contribute to differences in child health outcomes, with urban children generally having better access to healthcare and education [14, 15]. A study by S. M. Sipone et al. (2011) highlighted how maternal factors such as age, nutrition, and education significantly affect child health, nothing that teenage mothers are more likely to give birth to underweight or preterm babies [16]. Additionally, research by J. Dyment et al., (2013) examined the relationship between maternal anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and their impact on adverse birth outcomes, as well as, in some cases, advanced motor development [17]. Access to diverse outdoor play areas can positively influence children’s physical health by encouraging physical activity [18].

Research on child development has shown that cultural and religious beliefs significantly influence various aspects of a child’s growth. These beliefs shape health perceptions, dietary habits, healthcare-seeking behaviour, and breastfeeding practices [16, 19, 20]. Furthermore, low birth weight and preterm deliveries can lead to long-term cognitive and socio-emotional challenges, increasing the risk of chronic health conditions [21]. Another growing concern is childhood obesity, which can result in metabolic disorders such as high blood pressure and diabetes [22].

Malnutrition continues to be a pressing issue in Bangladesh, contributing to illness and mortality among children [22]. Despite extensive research on child health, there is a significant gap in understanding the combined impact of multiple determinants on children’s physical health in Bangladesh. Existing studies often focus on isolated factors rather than a holistic approach encompassing socioeconomic, demographic, maternal, and environmental influences.

Given these multifaceted determinants, it is essential to conduct comprehensive cross-sectional studies to identify and address the factors influencing child physical health development in Bangladesh. This study aims to examine the key determinants affecting child physical health development in the country and provide an in-depth analysis to bridge the existing literature gap. By identifying these key determinants, this research will offer evidence-based recommendations for policymakers and public health practitioners to enhance child health in Bangladesh.

This study examines the socioeconomic, demographic, and cultural determinants of physical health development among Bangladeshi children aged 6 to 10 years. A two-stage sampling approach was employed to ensure representativeness.

In the first stage, four divisions—Dhaka, Chattogram, Mymensingh, and Rajshahi were randomly selected from the eight administrative divisions of Bangladesh. In the second stage, 33 elementary schools (17 government and 16 private institutions) were randomly chosen from these selected divisions to ensure diversity in school type and regional representation.

Children aged 6 to 10 years were included based on parental presence and consent from the selected schools. Only those whose parents were available at school on the day of data collection and who provided verbal consent participated in the study. Structured interviews were conducted with parents to gather information on socioeconomic status, demographic characteristics, and their children’s physical development.

Children who were absent on the survey day or whose parents did not provide consent were excluded from the study. This two-stage sampling strategy facilitated the inclusion of a diverse and representative sample while addressing logistical constraints in data collection.

The dependent variable of this research is Children’s Physical Health, which is evaluated through six primary indicators, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (Very Poor = 0, Poor = 1, Fair = 2, Good = 3, Very Good = 4). The indicators consist of the ability to Recover from Disease – which shows the child’s immune response and how quickly they recover from common illnesses. Restlessness – assesses the child’s tendency to be hyperactive, fidgety, or unable to remain calm. Sleeping Performance – encompasses the quality and length of sleep, along with how often the child wakes up during the night. Playing Intention – measures the child’s eagerness and willingness to participate in physical play. Self-control ability – reflects the child’s capacity to manage emotions and behaviours in social situations, and Motor Skills – reviews coordination and the capability to perform physical activities like running, jumping, and grasping objects. Together, these indicators offer a thorough perspective on children’s physical health.

Explanatory variables included a variety of socioeconomic and demographic parameters, such as gender (boy, girl), place of family residence (urban, rural), and house types, which were divided into three categories: single-family homes, apartments, and multi-family dwellings. Family types included joint families and nuclear families.

Among the demographic birth factors considered were the following: birth weight (less than 2.5 kg, 2.5–3.5 kg, > 3.5 kg), cesarean section delivery (yes, no), premature birth (yes, no), and breastfeeding status during the first six months (always breastfed, breastfed and formula-fed, always formula-fed). Additional factors included whether the mother took calcium-related drugs during pregnancy (yes, no), the mother’s nutritional status (poor, adequate), psychological stress during pregnancy (yes, no), current use of any family planning method (yes, no), and the mother’s age at the time of the child’s birth (less than 18, 18–25, 25–30, 30 + years).

Parents’ educational attainment was classified into four categories: illiterate, primary, secondary, and higher education. The father’s employment status was categorized into six types: government job, private job, daily labor, unemployed, remittance worker, and others. Monthly family income was divided into four ranges: less than 10,000, 10,000–20,000, 20,000–40,000, and more than 40,000. Religion was classified into two categories: Muslim and Hindu.

After a comprehensive review of the existing literature, the authors developed a structured questionnaire for this study [23]. The questionnaire encompassed parental health during pregnancy, as well as challenges encountered by the child before and after birth, including early childhood illnesses and preterm birth. Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews with parents to collect responses. Parental observations of their children served as the basis for assessing physical health development. The questionnaire was structured into three main sections. The first section included neonatal information such as the child’s age (number), gender (male or female), religion (Muslim, Hindu, or others), birth weight (< 2.5 kg, 2.5–3.5 kg, > 3.5 kg), early childhood disease (yes, no), premature birth (yes, no) and breastfeeding status in the first 6 months (always, breastfeed and formula milk, always formula milk). The second part provides information about parents’ socio-demographic traits and health status. The variables included in the second section were father’s age, mother’s age, number of household members, father’s and mother’s education (less than secondary level, secondary level, higher secondary level), father’s occupation (not employed, private service, government service, daily work, remittance worker), monthly family income (less than 10,000, 10,000–20,000, 20,000–40,000, and more than 40,000), family types (joint family, nuclear family), location of residence (urban, rural), mother’s age at childbirth (less than 18, 18–25, 25–30, 30+), maternal history of particular drug use throughout pregnancy (yes or no), Poor nutrition during pregnancy (No, Yes); Psychological stress during pregnancy (Yes, No). Parents’ education, occupation, family type (joint/nuclear), present residence, and monthly family income were all key characteristics utilized to assess socioeconomic status.

Finally, the socioeconomic status was divided into three categories: low, middle, and high. Mothers’ psychological stress levels during pregnancy were assessed based on their self-reports and use of antidepressants at the time. The third portion used the following domains to assess childhood physical health development outcomes: recovering from disease, rating the child’s restlessness, rating the child’s sleeping performance, rating the child’s playing intention, rating the child’s self-control ability and motor skill (picking up and holding tiny objects, standing, running, jumping, and so on).

The current study included six items to distinguish children’s physical health. Each item was coded with five levels: 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. Where 0 means that the child’s physical health is very poor, 1 indicates poor physical health, 2 suggests medium physical health, 3 indicates good physical health, and 4 represents extremely good physical health. The CPHS considers the following items: Adding all six factors yields a total physical health score (TPHS) ranging from 2 to 24. The resulting TPHS was transformed into a score ranging from 0 to 1 by dividing the TPHS by 24 for each child. Let \(\:{V}_{ij}\) be the value of the \(\:{j}_{th}\:\)category of the \(\:{i}_{th}\) item responded by the parents of the children. Now the total physical health score (TPHS) for that child can be calculated by,

$${\rm TPHS } = \:\sum\:_{i}\sum\:_{j}{V}_{ij}$$

(1)

Where i = 1,2,3,. … … 0.6 and j = V = 0,1,2,3,4.

Now the Childhood Physical Health Score (CPHSc) can be calculated by the formula,

$$\:\text{C}\text{P}\text{H}\text{S}\text{c}\:=\:\frac{TPHS}{{TPHS}_{max}}\:=\:\frac{\sum\:_{i}\sum\:_{j}Vij}{{TPHS}_{max}}$$

Here \(\:{TPHS}_{max}\) can be obtained when j = 4 for all i.

The range of the CPHSc lies between 0 and 1, i.e., 0\(\:\le\:CPHS\le\:1\). CPHSc will be 0 when

j = 0 for all i, and 1 when j = 3 for all i.

This score is the Childhood Physical Health Score (CPHSc). The score tending from 0 to 1 indicates that the severity of physical health increased.

A two-stage sampling technique was employed in this study to collect data on the physical health development of children. In the first stage, four administrative divisions of Bangladesh—Dhaka, Chattogram, Rajshahi, and Mymensingh—were randomly selected. According to the Annual Primary School Census 2021, Bangladesh had 118,891 primary-level educational institutions, including 65,566 government primary schools and 4,799 private primary schools.

In the second stage, 40 schools were randomly selected from these divisions, and written applications for data collection were submitted. Of these, 33 institutions granted permission for participation. The required sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for a finite population, ensuring statistical validity and representativeness. The Cochran’s formula for sample size determination for the finite population is.

$$n = \frac{{n}_{0}}{1+\frac{{(n}_{0}-1)}{N}}$$

(2)

Where N is the size of the finite population, \(\:{n}_{0}\) is the sample size for an infinite population, and \(\:{n}_{0}\:\) be defined as

$$\:{n}_{0}=\frac{{z}^{2}pq}{{e}^{2}}$$

(3)

Here, z is the critical value of excepted confidence level, p is the proportion of a certain attribute presented in the population, q = 1-p, and e is the level of precision. Now if we consider 5% level of significance or 95% confidence interval, we have z = 1.96, considering the expected proportion of the study’s attribute is 50%, i.e., p = 0.5, q = 1 − p = 0.5, and e = 0.05. Putting all these values in Eq. (3), we can get \(\:{n}_{0}\) = 384.16\(\:\approx\:\)384. According to the Ministry of Primary and Mass education, the estimated number of primary school children in Bangladesh is 16,230,000. Hence, the population size for this study is N = 16,230,000. Now, using the value of N and \(\:{n}_{0}\), we have from Eq. (2)

$${\rm n}=\:\frac{384}{1+\frac{384-1}{16230000}} = 383.99\:\approx\:384 $$

(4)

The appropriate sample size for this study was determined to be 384 children. To account for potential issues such as incomplete responses and participant withdrawal, data collection efforts targeted 450 parents. Ultimately, complete responses were obtained from 401 participants, resulting in a response rate of 89.11%.

A team of trained professionals conducted face-to-face interviews with parents, who were informed that completing the questionnaire would take approximately 5–10 min. All collected data were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis. The data collection period spanned from October 1, 2023, to March 1, 2024.

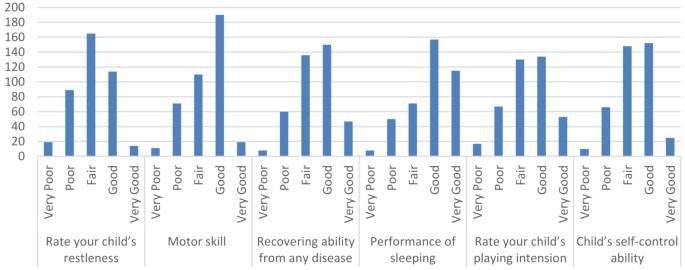

Since children were unable to provide information regarding their physical, socioeconomic, and demographic conditions, responses were obtained from their parents. A detailed illustration of the children’s physical health, as examined in this study, is presented in Fig. 1.

This study employed list-wise deletion to manage missing data, ensuring that all analyses were conducted using complete cases. The dependent variable, Child Physical Health Score (CPHS), is a numeric variable ranging from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate better physical health conditions. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests confirmed the non-normality of the study variables (p < 0.05), as presented in Table 1. Due to the non-normal distribution of CPHS, traditional parametric regression methods, such as ordinary least squares (OLS), were deemed unsuitable. Instead, generalized linear models (GLMs) and other non-parametric approaches were applied to account for the data distribution.

To begin the analysis, a frequency distribution of all explanatory variables—covering children’s characteristics, parental socioeconomic status, and demographic traits—was generated to provide an overview of the dataset. Next, bivariate analyses were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis H test. The Mann-Whitney U test was applied to assess differences in CPHS across binary categorical variables, while the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used for categorical variables with three or more groups [24]. The variables identified as important in the bivariate analysis were considered in the multivariate analysis.

Four generalized linear regression (GLM) models: generalized linear gamma regression (GLGR), generalized linear beta regression (GLBR) models, generalized log-normal regression (GLNR), and generalized exponential regression (GLER) have been applied to assess the significant impact of different socioeconomic and demographic variables on physical health. To determine the optimal model, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were calculated for each of the four [24]. The values of AIC (AIC: -488.9162) and BIC (BIC:-365.1034) in Table 2 were found to be the lowest for the GLNR model compared to the other three models, indicating that the generalized log-normal regression model is better than other models. The log-normal model allowed us to account for the positively skewed distribution of the dependent variable (child physical health scores), providing coefficients that are interpretable in terms of multiplicative effects. This is particularly useful for understanding proportional changes in health outcomes.

Hence, the results of the GLNR model have been extracted for this study and prepared the results accordingly. Kendall’s tau_b and Spearman’s rho correlation were used to analyze the link between physical health and other explanatory variables [24]. The statistical analysis was conducted using the software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) v25 and R version 4.3.2.

Figure 1 depicts the frequency of the physical health indicators used in this investigation. The figure shows that 190 children had good motor skills (47.4%), 150 demonstrated good disease recovery ability (37.4%), 157 showed good sleeping performance (39.2%) and 134 exhibited a positive child’s playing attitude (33.4%). Furthermore, the survey discovered that 152 (37.9%) of children exhibited high self-control abilities. These findings reflect the complexity of children’s physical health. While the majority of indicators yielded positive results, several places had slightly lower percentages. For instance, child restlessness 114 (28.4%) said that specific children required more care for their physical well-being.

Tables 3 and 4 exhibit general frequency distribution tables generated to help understand the characteristics of the explanatory variables employed in this study. Regarding educational institutions, government schools received more students (68.1%) than private schools (31.9%). With 50.6% of girls and 49.4% of boys participating, the gender breakdown was almost equal. The division Chattogram accounted for the greatest percentage of children (30.2%). Participants’ religious makeup leaned more towards Muslims (82.8%) than Hindus (17.2%). Although there was variation in birth weight, the majority (52.9%) of the children were born with a weight between 2.5 and 3.5 kg. A significant majority of children (55.6%) had experienced early childhood illnesses, and nearly an equal proportion was born via cesarean Sect. (48.6%). Most children were not born prematurely (63.8%) and were nursed with formula milk for the first six months (56.4%). Furthermore, most parents gave their children supplemental food/milk on occasion (70.6%) and allowed them to play/go outside/meet friends on occasion (46.9%).

Table 4 shows that the majority of parents (74.1%) use a family planning approach. In terms of fathers’ education levels, only 16.2% (n = 65) have a primary level, 51.1% (n = 205) have secondary education, and 32.7% (n = 131) have further education. Table 4 reveals that 13.2% (n = 53) of the mothers had a higher education. The father’s occupations varied, with a significant presence in private (32.2%) and government jobs (23.2%). Monthly family income distribution ranged from less than 10k (5.5%) to 20k-40k (51.6%). The most frequent kind of housing was single-family dwellings (43.9%), followed by apartments (26.2%) and multi-family homes (29.9%). Urban areas were slightly more prevalent (59.4%) than rural regions (40.6%). The maternal age at childbirth varied, with a considerable proportion falling between the 18–25 age group (59.6%). Many children (n = 215, 53.6%) belong to nuclear families, whereas 46.4% (n = 186) live in joint households. The findings revealed that 52.0% (n = 209) of mothers had inadequate nutrition, and 66.7% (n = 268) experienced psychological stress during pregnancy. Table 4 also showed that 63.4% (n = 255) of pregnant women took calcium-related medications.

Table 5 represents the results of bivariate analysis exploring the association or significant mean rank or median difference of physical health among different categories of the explanatory variables. The Mann-Whitney U tests demonstrate no significant differences in the median scores of CPHSc between school types (Mann-Whitney U = 16899, p > 0.05) and religion (Mann-Whitney U = 9796, p > 0.05). However, gender (Mann-Whitney U = 17337, p < 0.05) and early childhood disease (Mann-Whitney U = 15134, p < 0.05) emerge as significant factors associated with children’s physical health. Specifically, premature birth (Mann-Whitney U = 15390, p < 0.05), mother’s poor nutrition (Mann-Whitney U = 17192, p < 0.05), psychological stress during pregnancy (Mann-Whitney U = 15066.5, p < 0.05) also demonstrates significance in influencing physical health outcomes. Conversely, variables such as child’s delivery by caesarean section, family planning method, type of place of residence and family type show no significant associations with physical health.

In addition to the Mann-Whitney U test, the Kruskal-Wallis H test for testing the significant mean rank difference of CPHSc has been calculated and presented in Table 6. A significant difference is found between the children who have the opportunity to play or go outside or meet with friends (Kruskal-Wallis H = 10.824, P < 0.05), and the highest mean physical health score was observed in the children who were always given an opportunity to play/going outside/meeting with friends (0.6239\(\:\pm\:0.14700)\). Given child supplementary food/milk (Kruskal-Wallis H= 6.309, P<0.1) and the division (Kruskal-Wallis H= 12.326, P < 0.05) were found to be significant with physical health outcome. Furthermore, significant disparities are observed based on the father’s education levels (Kruskal-Wallis H = 14.326, P< 0.05) and fathers’ occupation (Kruskal-Wallis H= 11.177, P< 0.05) with higher-educated fathers and fathers who do private jobs correlating with higher physical health scores. Additionally, monthly family income (Kruskal-Wallis H= 28.517, P < 0.05) and the type of house (Kruskal-Wallis H= 6.012, P < 0.05) also exhibit significant associations with physical health outcomes, with lower-income households and individuals living in multi-family homes reporting lower physical health scores. Moreover, the table showed that the mother’s age at the time of birth of that child was also significant (Kruskal-Wallis H= 8.844, P < 0.05) with the score of physical health, with individuals born to mothers aged less than 18 showing lower physical health scores (0.5524\(\:\pm\:0.14149)\:\)compared to other age groups.

Table 7 shows a positive correlation coefficient between physical health scores and several demographic variables, including the child’s age, the father’s age, the mother’s age, and the number of household members. For instance, the positive coefficients suggest that with the increase in the parent’s age, the child’s physical health score also increases.

Table 8 illustrates the impact of socioeconomic and demographic factors on children’s physical health development. Early childhood disease shows a significant negative impact on physical health (OR: 0.9537, p = 0.000769), suggesting that children with early childhood diseases are about 4.63% less likely to have good physical health compared to those without such diseases. Infrequent opportunities for outdoor play also negatively impact physical health. Specifically, children who sometimes (OR: 0.9644, p = 0.025740) or seldom (OR: 0.9451, p = 0.007235) have the chance to play outside are respectively 3.56% and 5.49% less likely to have good physical health, compared to children who always play outside. The influence of gender seems to be minor but statistically significant. compared to boys, to be in better physical condition (OR: 0.9693, p = 0.025684). Additionally, children from the Rajshahi division have better physical health outcomes, being 1.05 times more likely (OR: 1.0496, p = 0.021429) to be in good health compared to children from other divisions. Moreover, income has a significant impact on physical health. Children from lower income families are roughly 7.53% less likely than those from families with higher incomes to be in good physical health (OR: 0.9247, p = 0.015046). Furthermore, providing supplementary food sometimes (OR: 1.0583, p = 0.001819) or seldom (OR: 1.0605, p = 0.026123) significantly improves children’s physical health, with these children being about 5.83% and 6.05% more likely, respectively, to have good physical health compared to those who are never provided supplementary food.

The study focused on the effect of socioeconomic, demographic, dietary, parental, and birth-related factors on the physical health development of children in Bangladesh. The bivariate study revealed that a parent’s socioeconomic level significantly impacted their children’s physical health. Previous research in various settings has shown that children from the richest homes are more likely to receive treatment than those from the poorest households [25]. An earlier study found that children of young mothers (≤ 19 years) in low- and middle-income countries are disadvantaged at birth and during childhood, with increased chances of low birth weight, preterm birth, stunting, and failure to complete secondary schooling [26]. A population-based longitudinal study in the United States found that low levels of household income are connected with multiple lifetime physical disorders and suicide attempts, and a decline in household income is associated with an increased risk for incident physical disorders [27].

The findings of this study demonstrated that maternal poor nutrition during pregnancy significantly impacts children’s physical health. Previous research indicated that malnutrition caused developmental delays, and children who were hungry or frequently unwell were more likely to face developmental issues [28]. In addition, the study found no link between birth weight and children’s physical health. On the contrary, a study in the US found a significant association in children with ‘’normal’’ birth weights of 2,500-2,999 g were more likely than those with birth weights of 3,500-3,999 g to have physical retardation, cerebral palsy, learning disability without physical retardation, and other developmental delay [29]. Research on the population of England also identified the significance of early birth factors such as birth weight and socioeconomic class in children’s psychological well-being [30].

This analysis discovered that house type considerably impacts children’s physical health, where lower-income households and individuals living in multi-family homes report lower physical health scores. Similarly, a study conducted among Austrian children reveals that children who reside in multiple-family dwellings manifest significantly stronger associations between residential density and a standardized self-report index of psychological health as well as teacher ratings of behavioral conduct in the classroom in comparison to their counterparts residing in either single-family detached homes or row houses [31].

This study found that father education significantly impacts children’s physical health. A longitudinal study conducted in Indonesia also indicated that although the father’s education has a substantial impact on child’s physical health, the mother’s education shows no significant association [32]. This study showed that children with early childhood diseases are less likely to have good physical health compared to those without such diseases. A study showed that poor physical fitness in childhood is connected with a variety of unfavorable health-related outcomes in children, including high blood pressure, cholesterol, obesity, and chronic disease [33].

Gender also plays a role, with girls being slightly less likely to have good physical health than boys. Gender is widely shown to be a correlate of objectively measured physical activity in youth samples, with boys on average engaging in more activity than girls, with the effect magnitude relatively consistent across ages [34]. A recent study revealed gender differences in health, physical growth, and development in early childhood in three groups of medically at-risk newborns, finding that prematurely born girls showed better cognitive and motor development than prematurely born boys [35].

In this study, psychological stress during pregnancy significantly influences physical health outcomes. Recent research reveals that a woman’s psychological condition during pregnancy can significantly affect learning, motor development, and conduct in offspring [36]. In China, pregnant women with a second child report low to moderate levels of stress [37]. Prenatal anxiety is widely recognized as a potential risk factor for unfavourable birth outcomes such as preterm birth, low birth weight, and preeclampsia [38]. An Australian study found that high scores for stressful life experiences during pregnancy are associated with BMI, overweight, and obesity in offspring [38].

The study found that the mother’s age at the time of birth of that child also significantly impacts the child’s physical health. A review of older maternal age and child behavioural and cognitive results indicated that older maternal age appeared to exhibit a protective influence on offspring behavioural and cognitive outcomes [39]. A study in Thailand, on the other hand, found that increasing maternal age was associated with a lower risk of developmental vulnerability for infants born to women aged 15 to 30 years [40].

The highest mean Physical Health score was observed in the children who were always allowed to play/go outside/meet with friends. The outdoors is an open atmosphere where booming voices and huge, exuberant, and risky motions are permitted, which provides youngsters a sense of excitement and freedom of being and doing [41]. Outside, children are exposed to sunlight, fresh air, and natural and living creatures, which benefits their health and development [41]. Furthermore, the outdoors is a free, accessible, and constantly changing environment where children may interact with nature, experience natural phenomena, meet new people, and become familiar with their surroundings, allowing them to feel comfortable and independent in moving throughout the community [41].

The study included questions about the mother’s health status during pregnancy, early life and the physical health of the children, which could result in recall bias. Although the study examined a broad range of factors, certain variables, such as environmental pollutants were not included. One notable limitation of this study is that madrasa students, who constitute a significant portion of the child population in Bangladesh, were not included in the sample. The findings of the study have strong practical implications for child health interventions and policy-making in Bangladesh. Using two-stage sampling ensured that urban and rural populations were adequately represented, providing a more comprehensive understanding of child health nationwide.

Physical health refers to a state of well-being in which all internal and external body systems, including organs, tissues, and cells, function optimally. This study examines the key factors influencing children’s physical health in Bangladesh. Our findings highlight several critical determinants, including gender, regional division, early childhood illnesses, access to play and social interaction, parental education, household income, maternal age, and housing conditions.

Maternal factors, such as inadequate nutrition, psychological stress during pregnancy, premature birth, and supplementary food intake, play a significant role in shaping children’s health outcomes. In Bangladesh, children who experience early childhood illnesses tend to exhibit poorer physical development. Conversely, those with greater opportunities for outdoor play demonstrate improved health outcomes compared to their peers with limited physical activity. Moreover, access to supplementary nutrition is associated with better physical health among children.

The insights from this study can contribute to public health initiatives aimed at improving children’s physical health in Bangladesh. Addressing maternal health concerns, reducing socioeconomic disparities, and promoting opportunities for physical activity could significantly enhance the overall well-being of children in the country.

The corresponding author will provide data upon request.Riyadh Hossain Email: [email protected].

- CPHSc:

-

Child physical health score

- GLBR:

-

Generalized linear beta regression

- GLNR:

-

Generalized log normal regression

- GLGR:

-

Generalized linear gamma regression

- GLER:

-

Generalized linear exponential regression

- MICS:

-

Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey

We thank the respondents for their consent and participation in this study.

The author(s) received no specific grant for this work.

This study was approved by the Noakhali Science and Technology University Ethical Committee (NSTUEC), and the ethical approval number of this study is NSTU/SCI/EC/2022/90(B). Written consent was taken from the primary school authorities. As the study did not involve any medical or surgical procedure experimented on humans, verbal consent was obtained from primary school children’s parents (either fathers or mothers). The ethical committee approved the parents’ verbal or oral consent for their children. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were ensured the confidentiality of their identity and given data. The nature of the study was entirely voluntary, and no incentives were given for participation.

Not applicable to this article.

The authors declare no competing interests.

There is no conflict of interest among the authors. All authors read the final manuscript and approved it.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Hossain, R., Faruk, M.O. & Begum, N. Determinants of child physical health development in Bangladesh: a study of key socioeconomic and cultural influences. BMC Public Health 25, 2447 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22843-9