BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 2392 (2025) Cite this article

The prevalence of adverse mental health outcomes experienced by deaf adults – members of deaf communities connected through a shared sign language and culture is greater than that faced by their hearing counterparts. In addition to everyday life stressors, deaf people can experience further communication related stressors. For this group, early life communication and language deprivation is a significant contributing factor to subsequent adverse mental health outcomes. This study aimed to understand how deaf people viewed the impact of inadequate access to early life communication on their mental health across their life.

One-on-one semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 16 deaf Australian adults who identified as having mental health challenges. Interviews were conducted in Auslan and inductively coded using thematic analysis.

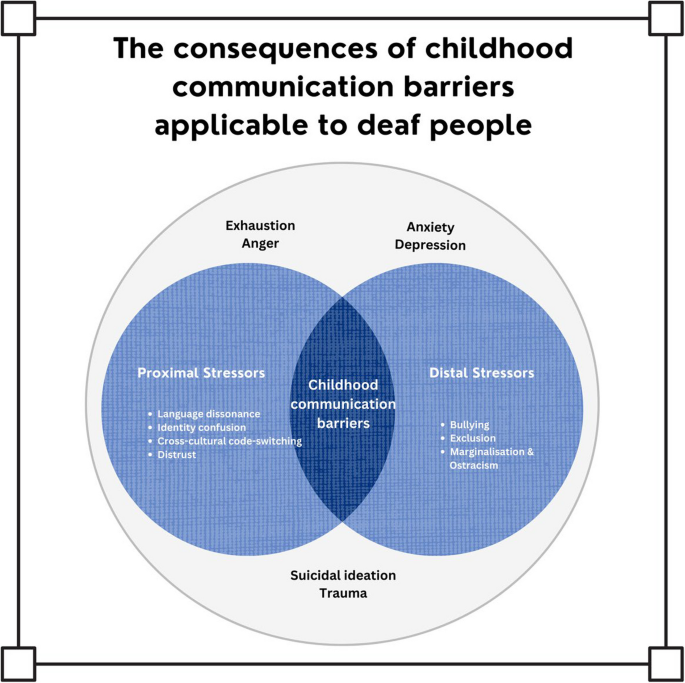

Participants attributed various forms of mental ill-health to interactions with people who could not sign, particularly within the family and school environments. Proximal stressors such as language dissonance, identity confusion, cross-cultural code-switching, and distrust were identified by participants. Distal stressors included three themes: bullying, exclusion, and marginalisation and ostracism. These stressors were perceived to be linked to experiences of mental ill health including periods of exhaustion, anger, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation.

The study highlights deaf Australians’ perceived negative impacts from proximal and distal communication-related stressors during childhood on mental health outcomes. Addressing communication barriers in childhood through the implementation of interventions and support strategies may help to avoid adverse mental health outcomes for deaf adults.

There are more than 70 million deafFootnote 1 people who use sign language worldwide [2]. The limited available data estimates that among the 3.6 million Australians with hearing loss [3], the number of Auslan (Australian Sign Language) users is considerably smaller, with the estimated number being more than 16,000 people [4]. These statistics are comparable to other countries with health care systems similar to Australia where the congenital deafness rate ranges from 1 to 3 per 1,000 newborn babies [5]. Individuals who form part of deaf communitiesFootnote 2 identify as members of a cultural and linguistic minority group [7].

Communication is a fundamental human need and is the foundation of human interaction, facilitating social connection, understanding, and the establishment of meaningful relationships [8]. This requires a shared language for communication of any depth to occur. However, by far the majority of deaf children are both born into and continue to be exposed to situations in which there is a lack of accessible language [9]. Hall et al. [10] have described the mismatch that deaf people experience between their perceptual abilities and the surrounding majority language environment. Within the context of this article, the term ‘inadequate communication’ draws on this idea of a ‘mismatch’ and the subsequent impact it has on a deaf person’s ability to fully participate in social, educational, or professional activities.

Despite being inter-related and frequently conflated in everyday usage, the terms ‘language’ and ‘communication’ are not synonymous. For Chomsky [11], language is a tool of communication and a shared set of symbols used to exchange thought or communication between two or more people, whereas communication refers to an effort to get people to understand what one means. Humans can communicate to some extent without language, but communication of any depth requires language [12]. Similarly, communication at more than a superficial level is only possible when there is a shared language between two or more people involved.

The critical period for language acquisition occurs during the first five years of a child’s life [13], at which point a child is expected to have mastery in their native language(s) [10, 13]. If a child does not achieve fluency in a language by the age of five, they may never become fully fluent in any language [14].

Failure to develop language mastery during the early years may lead to difficulties in learning, the ability to establish social relationships, behaviour and emotion regulation [15]. Deaf children have the capacity for typical intellectual potential; however, their development is often compromised as they grow up without adequate access to a (spoken or signed) language necessary for acquiring language mastery [16]. Language deprivation may also begin during this period, due to a chronic lack of full access to a natural language [17,18,19], which contributes to the developmental barriers that deaf children face. Hall et al. [10] report that the long-term implications of limited language are evident in reduced cognitive development, social and emotional skills, school readiness and academic outcomes.

For many deaf people, sign language is the most accessible and preferred mode of communication [10, 16]. Age-appropriate mastery of a natural sign language is more likely to be achieved for deaf children because the visual modality is not compromised by hearing loss [10]. Sign languages are the natural languages of deaf communities. Sign languages are visual-gestural languages with distinct phonological, morphological, syntactic and discourse organisation [20]. Accounting for all other variables, a deaf child who is proficient in sign language does better academically than deaf children who do not sign well [14]. Yet, it is estimated that worldwide, two percent of deaf children receive early signed language exposure [21] and only 1–2% are provided with an education with a sign language as the language of instruction [22]. Similarly, only 8% of deaf children in Australia receive early, immersive access to a signed language [23].

Globally, between 90%−97% of deaf children are born to hearing parents with little or no previous experience with sign language [24, 25]. Apart from deaf children who have access to sign language from birth (mostly those with deaf parents), most deaf children experience barriers in accessing the chosen language of their family, with very few families being willing or able to learn a sign language for their deaf child [26].

Inadequate childhood communication may impact on mental health outcomes in adulthood. For example, a systematic review conducted by Dall et al. in 2022 [27] found that earlier onset and more persistent mental health problems were apparent in children who had the most severe social communication difficulties. Studies involving special populations such as children with emotional or behavioural difficulties, those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds, or those with language disorders or challenging personality traits reported higher rates of social communication issues compared to typically developing children [28,29,30]. Additionally, these children experience worse mental health outcomes when they have additional social communication difficulties.

There are many ways to understand and measure mental health. Mental health assessment often includes the measuring of communication skills, with early communication challenges recognised in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for diagnosing communication disorders, including Unspecified Intellectual Disability (Intellectual Developmental Disorder) [31]. An individual’s verbal and nonverbal communication is critical throughout all aspects of their mental health assessment, diagnosis, treatment and support for recovery [32, 33]. Communication disorders are common co-morbidities with mental health conditions, with estimates showing that 60% of adults with mental health disorders have communication and discourse impairment [34].

Importantly, mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders. The World Health Organization emphasises the need for a holistic understanding of mental health and wellbeing, recognising that adverse mental health occurs along a continuum and is influenced by internal and external factors, with relationships playing a central role [35].

Research has found that deaf people experience a higher prevalence of adverse mental health outcomes when compared to the general population [36]. In Australia, the National Health Survey 2017–18 highlighted that the prevalence of anxiety and/or depression among individuals with hearing loss (including deaf individuals) was 14.8%, relative to 9.7% reported among the hearingFootnote 3 population [38]. Similarly, the Australian Survey of Disability, Ageing, and Carers 2017–18 found that 14.4% of individuals who experienced anxiety and depression also identified as being completely or partially deaf compared to 6.2% of the population without deafness or hearing loss who experienced anxiety and depression [39].

A range of factors reported amongst the deaf population may help to understand the rate of their poorer mental health outcomes. For example, both discrimination and disadvantage are due in part to the negative perceptions of deafness by hearing people [40], poor child-caregiver communication [41, 42] and limited academic achievement [43]. These outcomes continue into adulthood, manifesting through barriers to employment [44,45,46] and in accessing health care information [47].

There is limited research from the perspective of deaf people as to what influences their mental health [42]. Incorporating lived experiences into analysis enhances the relevance and practical impact of any conclusions drawn. The meaningful involvement of stakeholders affected by the research from the outset is therefore likely to be advantageous for the quality of the research [48, 49].

This study aimed to understand how deaf people viewed the impact of early life communication access on their mental health across their life. Use of a participatory approach meant that the research was informed by deaf people’s views, thereby increasing understanding of the connection between communication and mental health [50].

This study used a qualitative research design. This was selected given its appropriateness as a method when undertaking research with traditionally marginalised and vulnerable individuals, such as the deaf community [51, 52]. In-depth one-on-one semi-structured interviews were used to explore deaf peoples’ perspectives on the impact of early childhood communication access and their mental health across their life. Specifically, qualitative inquiry was used to examine participants’ social circumstances. Underlying the research was the assumption that people use “what they see, hear, and feel” to make sense of social experiences [49].

Participants were recruited using purposive sampling [49] within the deaf community, deaf networks, organisations, and social media platforms. Recruitment videos were disseminated in Auslan with English subtitles on social media. Flyers titled “Looking to interview Deaf and Hard of Hearing people about life experience” were circulated via deaf clubs, advocacy organisations, and community groups. Further, snowball sampling [53] was used to expand the participant pool.

Participant eligibility criteria encompassed:

We ensured participants met the criteria through use of a demographic screening tool accessed through a QR code. Participants were asked about their own and their parents' hearing status, as well as their own Auslan language fluency, gender, age, cultural background, education and residential location.

Participants were provided with a Plain Language Statement (PLS) with detailed information about the study in written English and a QR code for the Auslan version. Participants had access to an initial meeting with RM to discuss the PLS and the research, before returning a signed consent form by email. This is in line with best practice for communication with deaf people [54].

It is increasingly common for research with and from within minority groups to account for the positionality of the research team, adding accountability and rigour to the research [55]. Manohar [56] highlights the importance of both recognition and perception of the insider/outsider status of researchers when conducting studies of culturally and linguistically diverse groups. As a deaf researcher and Auslan user, RM conducted data collection in Auslan. This facilitated an authentic understanding of participants'experiences without the potential loss of nuance that may occur in an interpreted interaction [57]. The research team also included a hearing woman and Auslan-English interpreter (AO), a hearing child of deaf adults (KB), a deaf researcher (RA) and a hearing researcher (JD). Authors’ contributions to the research are included in the ‘Acknowledgements’ section.

RM engaged with participants through two Zoom-based encounters, with the second encounter video recorded and transcribed for data analysis. The initial research encounter, lasting 30 min, enabled RM to discuss the research, establish cultural safety along with rapport and explain the research purpose. The second encounter was a recorded Zoom interview which lasted approximately 1.5 h, and used open-ended questions to prompt discussion about participants’ experience with childhood language access and the potential impact this has had on their mental health across their life, thereby allowing multiple meanings to surface. The interview guide was developed and refined with reference to the literature and research team discussions. Appendix 1, containing the English version of the interview guide, has been attached as a supplementary file.

Certified interpreters translated the Auslan recordings into written English interview transcripts. This is necessary for written analysis as Auslan has no written form and also addresses concerns from deaf scholars [1, 58, 59] that participant anonymity is not maintained if the data is presented in video form [60]. Accuracy of the transcriptions was reviewed by an experienced deaf translator, from which point, pseudonyms were assigned to each participant to ensure anonymity. Participants were emailed their individual transcript for member checking [61] before data analysis commenced. Member checking was available using the English transcript, with the option of conducting this process over video in Auslan. Minor refinements were requested by two participants which were made accordingly.

This study used the Braun and Clarke’s [62] six step approach to thematic analysis. Three authors (RM, KB, AO) were involved in the thematic analysis process. RM developed the coding framework using an inductive approach that did not rely on any theoretical frameworks. This was reviewed and cross-checked by AO. RM coded the transcripts individually using open coding techniques [63]. Similar codes were used to construct the initial themes. This led to exploration of relevant frameworks, such as the Minority Stress Model [64] and Acculturation Theory [65] which helped to contextualise and refine the emerging themes with input from the authorship team. The Minority Stress model [64,65,66] focuses on the cumulative stressors both proximal (e.g., internalised stigma, self-concealment) and distal (e.g., harassment, violence, and discrimination) experienced by marginalised groups due to their minority status. In the context of signing deaf adults, the model is relevant as it highlights the intersection of and collective adverse impact of internal stressors, systemic barriers and attitudes of mainstream society. Further, Acculturation Theory [67], examines how individuals navigate and adapt when interacting with a dominant culture different from their own. For signing deaf adults, this theory provides a lens to understand their experiences with the hearing majority. Using inductive coding [68], themes were then categorised into proximal and distal stressors in line with the Minority Stress Model [64]. NVivo 12 [69] facilitated data management and results were then narratively summarised using illustrative quotes.

Forty individuals expressed interest in participating in this study. Seven participants did not meet the eligibility criteria. The final sixteen participants were identified using purposive sampling strategies [49] to provide a diverse group across gender identities, age, cultural background, location, and with a mix of deaf and hearing parents (Table 1).

We identified seven themes. These represented the early life communication barriers that were perceived to be associated with mental health outcomes. In line with the Minority Stress Model, four were categorised as proximal stressors and three as distal stressors. The themes are summarised in Fig. 1 and described below.

A diagram showing the consequences of childhood communication barriers applicable to deaf people with themes categorised as either proximal or distal stressors and the resulting mental health impacts

Proximal stressors due to poor communication in childhood, usually associated with delayed first-language acquisition, were reported to be associated with negative mental health outcomes by all participants. Participants described several sources of proximal stress arising from interactions in childhood with hearing people (particularly if they felt that they were being treated in an audisticFootnote 4 manner), and the perceived association of those experiences with their mental health outcomes. Four themes were identified: language dissonance, identity confusion, cross-cultural code switching and distrust. Descriptions of each theme are listed in the Coding Framework in Appendix 2.

Language dissonance

All participants described their experiences of the different linguistic proficiency, language preferences, cultural understandings, and communication styles of those around them at home and school. For participants, language dissonance was usually exemplified by other people with whom they interacted not being able to use sign language. For all participants whose teachers and/or parents did not sign, this led to outcomes such as misunderstanding, misinterpretation and/or or challenges in effective communication.

Participant 11 reflected on this experience within their family:

I would look at everyone’s mouths moving around me, and I really just put up with that. I didn’t know it at that time but that that was actually audism [...] I just took it for granted. I think I was just used to it because I was born deaf.

Language dissonance was also evident in participants’ stories of feeling left out of daily conversation at home. The continuous need to seek clarification of auditory information was epitomised by the repetitive inquiry of "What did you say?", which reportedly became a tension within the family for some participants. This inadvertently disrupted shared activities, such as watching television with a hearing sibling. These communication barriers were also perceived to lead to future workplace communication issues.

In addition, language dissonance was apparent in the early educational setting, which led to a lack of confidence. One example of this came from Participant 13 who said:

In Prep or Year 1, I was transitioned to a hearing class […] I started to feel uneasy because I didn’t know what was happening. All the other children were all speaking very quickly, I was watching their mouths move.

This lack of confidence emerged again in adulthood and resulted in adverse mental health outcomes:

I had no confidence, I had emotional problems, issues going around in my head, depression, and a breakdown. I didn’t know what was going on. I had that negative/anxious feeling when I was with hearing people.

Some participants experienced challenges during school when they changed communication methods during their developmental years. For example, Participant 5 transitioned from using sign language to using Cued SpeechFootnote 5 when they were 10 years old. They expressed the impact of the changes in their communication methods on their linguistic comprehension and expression:

I went to speech therapy and tried to talk [speak] but internally, I knew it wasn’t for me. I felt different because I was deaf and […] all the other children were hearing. I tried my best to lipread and […] when we were playing, there was tag and there was touch involved, it was very visual […]. Sitting with others which involved talking [speaking] was for hearing children and I wasn’t interested in being part of that.

In adulthood, 11 participants described how changes in communication methods created anxiety, with 12 participants describing a suicide attempt.

I had a mental collapse at the end of 2001. I was finished, I was not well […] I had thought about suicide and slitting my wrists, for the second time (Participant 5).

So, I had two instances [suicide attempts]. Both through really traumatic experiences…They had…triggered…Where I did decide that’s it [enough]…Done (Participant 3).

Some participants also expressed concern about the lingering impacts of their struggles with English in their primary and secondary schooling. The inability to express themselves fluently in written English generated an ongoing fear of utilising their vocabulary as adults and led to anxiety connected to past traumas.

Identity confusion

Participants recounted experiences of identity confusion (in relation to their identity as a deaf person) commencing in childhood. Participants associated the challenges with identity and a desire to appear "normal"in the mainstream world with anxiety about feeling inferior and societal perceptions which perpetuate negative stereotypes:

[…] to this day I am still struggling with my identity […] but it was really hard because my mental health, my identity, I was unsure as to whether my identity was hearing or deaf (Participant 2).

Participant 14 described their identity confusion:

I felt on the outer. I felt distanced from my culture and the deaf community, I didn’t want to associate and, tried to fit in the mainstream. Trying to show and act normal (Participant 14).

Cross-cultural code-switching

Several participants described cross cultural code switching—having to adjust their language or behaviour to fit a hearing culture. They described this as a way of minimising negative consequences for themselves.

[…] I felt a huge pressure [burden] […] to walk quietly, eat quietly, need to pay respect and say thank you, please. Because I didn’t want to be hurt (Participant 7).

Participants' narratives revealed the perceived need to please others, particularly those within wider society. They wanted to maintain harmony and ensure happiness of hearing individuals, which masked anger that extended into adulthood:

I wanted to see my mum happy, I wanted to see society happy, and I became a “pleaser”. I still have the same issue, because from my childhood I pleased people […] but for me, internally, I was angry, sad (Participant 14).

Distrust

Participants described experiences of interpreter-mediated communication which left them feeling powerless and frustrated. This view carried over into adulthood, for example, Participant 10 described an incident in their childhood where they felt that communication was compromised by insufficient interpreter skill. Participant 10 experienced a loss of trust in interpreters which has remained with them for many years.

I don’t have any trust in them [interpreters] because I always have at the back of my mind, what happens if they tell other people [...] I have witnessed interpreters telling the community confidential information [about deaf people] (Participant 10).

Participant 13 also highlighted the importance of trust in interpreter mediated communication:

Trust is a major issue, sometimes it can happen with interpreters [or any hearing person] […] if they try to control me, that makes me really annoyed (Participant 13).

Participants raised issues which could be interpreted to be distal stressors. Individuals recounted feelings of distance from others within their immediate environment either on a one-off or a recurring basis. All participants felt left out within family and school environments, with three themes identified namely: bullying, exclusion and marginalisation and ostracism. Descriptions of each theme are listed in the Coding Framework in Appendix 2.

Bullying

Participants highlighted bullying that occurred within familial and formal education settings with subsequent isolation and disconnection from peers culminating in emotional distress. For example, Participant 1 stated:

I was going to slit my wrists because in school my teachers bullied me, interpreters bullied me, students bullied me, students with additional disabilities even bullied me (Participant 1).

In a more extreme example, Participant 8 recounted:

My father’s idea was that I would be locked in a cupboard to try and improve my speech. I would practise speech sounds and my parents would listen from outside the cupboard and then the cupboard would be opened to let me out.

Schools were a common site for experiences of bullying even when a supportive home communication environment was present. As one participant said:

At home, everything was great as was the community, but it really hit me at school. It caused trauma and that’s when my mental health issues started [...] different teachers and the other students really bullied me (Participant 13).

This had enduring effects with Participant 13 going on to say:

I still do have issues due to the impacts of my past school experiences […] With relationships, with friends, relationships not in the deaf space but with hearing people.

Exclusion

Participants repeatedly described feelings of exclusion during childhood.

When I was growing up, I felt very lonely […] at school, both my sister [deaf] and I… really struggled to develop friendships and maintain friendship groups because of feeling different from them [...] I also felt excluded […] we could communicate but they were all hearing […] students always had their own [friendship] groups. I was always on the outer, by myself (Participant 3).

Participants also experienced exclusion during family mealtimes:

Everyone around the table, my family, brother and sister. All eating, but my brother and sister when they talked, mum interacted with them. But when I wanted to talk, I wasn’t allowed to (Participant 14).

For others, exclusion came via incorrect assumptions regarding intelligence and understanding:

There would be a joke and the hearing kids would say “oh don’t worry, you wouldn’t understand” (Participant 2).

Marginalisation and ostracism

Participants described how a lack of communication access within the home led to marginalisation and feelings of being left out, being misunderstood and/or emotionally neglected. These feelings led to poor mental health outcomes later in life. As one participant described:

My brother and sister, they had much more…they were the first people to know [anything] […] I was the last to know, that was frustrating (Participant 14).

Participants reflected on how feelings of frustration and anger as children were exacerbated in adulthood. As Participant 7 said:

I was always angry, I’d keep my patience for so long, but it would build up, and then when I cracked, I didn’t know how to stop. I couldn’t control it because I didn’t have any education on how to [act appropriately].

For participants from Aboriginal or multicultural backgrounds, the intersection of deafness and race compounded challenges:

I felt stuck in the middle, without an identity. I felt directionless. Also, I’m Aboriginal too. I’m black, brown skin. I was darker than everyone else (Participant 14).

I have an [Aboriginal] mob, but I never joined in because of communication. I didn’t know what they were saying […] I’m the only deaf one [in my area] (Participant 7).

I suffered from racism. Growing up for many years as a child I copped it because of my race and my skin colour, some of it was direct and some of it was indirect (Participant 1).

Seven central themes, representing proximal and distal stressors limiting communication access, were identified as negatively impacting mental health among signing deaf adults in our study. Specifically, these themes represent the challenges relating to communication and identity that arise from linguistic and cultural difference. Challenges also came from the behaviour of others, particularly the unwillingness of family members, teachers and peers who did not use sign language to adapt their communication. This aligns with the medical model of disability, in which disability is positioned as an abnormality to be eradicated or at least remediated so that people with disabilities conform as closely as possible to society’s idea of a normal person [73]. In this view, the stressors would be understood as inherent to participants’ deafness, rather than as the interaction between their deafness and society.

In line with the Minority Stress Model, participants’ negative experiences over time became internalised and functioned as both proximal and distal stressors [64]. For example, stories of language dissonance and marginalisation were reported in ways which indicated that participants had taken on the ideas of others and internalised them in their own sense of self. This is further evidenced when reviewing the video recordings of participant interviews. In Auslan and many other sign languages, the extended index finger is used to indicate people, places or objects in space. Different positions in space can be used to show the relative position of each. Most participants referred to hearing people using the pointing index finger at a position higher in space, meaning they perceived hearing people to be of higher status than themselves or other deaf people. Engberg-Pedersen [74] explains that the selection of spatial loci in sign language is influenced by conventions related to authority. Signers may assign higher spatial positions to individuals in authoritative roles, while placing less authoritative figures lower in space. This linguistic feature reflects broader societal ideologies of power and hierarchy. In this study, deaf participants often placed themselves 'lower' than the hearing people involved in their stories, allocating the hearing person a greater status and level of authority [75]. This use of space, therefore, serves as a representation of power dynamics between hearing and deaf individuals.

In homes without a shared language between the deaf participants and their families, participants felt excluded from every day and incidental family discussions, a phenomenon framed as ‘dinner table syndrome’ [18, 76]. Participants reported limited access to communication both within the family and at school during childhood, aligning with a study by Listman and Kurz [77]. Further literature has shown that deaf children who are not provided with a sign language early in their development are at risk of linguistic deprivation [78]. Hall [17] and Humphries et al. [14] also show that having an accessible language is protective for healthy psychological development. Our findings support these prior studies revealing that the absence of a shared linguistic framework resulted in anxiety about English language competency. Language deprivation for these individuals also contributed to an interplay of frustration, isolation and disconnection with hearing people, as well as thoughts of suicide.

Difference is not generally valued in society. Instead, sameness is seen as desirable [79]. Deaf people, commencing in childhood, are typically expected to change who they are, to fit in with the mainstream, to become ‘normal’[80]. Eight out of sixteen participants in this study specifically mentioned that identity confusion was associated with later adverse mental health outcomes. Identity suppression, educational barriers, and enduring stigma and discrimination have been found to collectively contribute to heightened stress, anxiety, and challenges to mental health and well-being for deaf people [40, 59, 81].

Deaf identity is central to the personal experience of being deaf [82]. Participants connected their experiences of ‘identity confusion’ to internal conflict between finding belonging and a sense of self in the deaf community and meeting the expectations of the hearing world. This was exacerbated by external characterisations in which some of these deaf individuals were equated to those with lesser intellect, or otherwise considered ‘not normal’.

Some participants in this study reported cross-cultural code-switching practices in line with previous research [81, 83]. This permeated their everyday interaction with the hearing world. Participants reported trying to act normal to align with the conditioned views of mainstream society that equated deafness with disability and with associated stigma [84]. Interactions with interpreters for some participants exacerbated feelings of disempowerment and distrust of hearing individuals. Meyer [64] framed stigmatisation by external people as a conflict between self-perceptions and others’ perceptions. This leads to a greater likelihood that the self-perception of a stigmatised individual is unstable and vulnerable. Thus, it is not surprising that despite participants in our study demonstrating resilience in navigating environments where different communication modes intersected [77], cross-cultural code switching was associated with negative mental health outcomes.

Establishing personal connection is important in initiating trust [85]. Studies of deaf people and interpreters often cite trust as the cornerstone of a successful interaction [86] despite this not necessarily being a reciprocal relationship, or trust even being desirable or possible as a marker of competence [87]. Participants highlighted the importance of trust when dealing with interpreters, with concerns about both interpreters’ skill level and attempts to exercise control. These findings align with research undertaken by Sheppard and Badger [88] who identified that reaching out for help was difficult for some deaf people with depressive symptoms due to concerns about interpreter confidentiality.

Bullying throughout school was one of the distal stressors reported by participants. Evidence shows higher rates of bullying among deaf adolescents compared to hearing students [89, 90]. This bullying, motivated by communication differences, can increase the risk of depression and other negative mental health outcomes [91]. In a scoping review of bullying of deaf and hard of hearing children, seven of the nine included studies reported that hearing loss was significantly associated with increased victimisation [92]. The consequences of bullying in this cohort included sleep issues and anxiety [92]. Increasing deaf awareness among hearing children, as well as more rigorous interventions to prevent bullying in the first place (especially within the school setting) is vital to bringing about change [93].

Our study highlights the experiences of marginalisation and ostracism of signing deaf adults in line with previous work undertaken on the difficulties experienced by deaf people in terms of educational social inclusion [94, 95]. These behaviours could be minimised with support from both regular and itinerant teachers of the deaf. For example, Power and Hyde [96] found that deaf students generally function socially (and academically) as successfully as most of their hearing peers in integrated classrooms when they received appropriate interventions from educational practitioners.

Children acquire language without instruction if they are regularly and meaningfully engaged with an accessible human language [97, 98]. The negative experiences of language dissonance shared by participants in this study support the need for early language intervention in childhood. Although parents need not be fluent signers for deaf children to benefit from their signing [99], responsiveness to cultural and linguistic diversity is critical for family-centred early interventions to be effective [100]. Examples of promising interventions within the literature relevant to enhancing communication access for deaf children include Norway’s Al Course Center [99], which delivers courses in sign language and communication for parents and extended family, while deaf children can concurrently partake in training in communication and sign language through play-based activities. The Center also provides the opportunity for deaf adolescents and adults to exchange experiences and build social networks as well as tools for improved quality of life and coping. In the United Kingdom, the DOT Deaf project (Developing Online Training with deaf people) [101] focuses on supporting deaf children to learn British Sign Language (BSL) by providing language therapy in BSL. Deaf professionals, also known as Deaf Language Specialists, are employed to work with children and young people who have difficulties learning sign language. Similarly, trained deaf guides are employed within Hands and Voices in the United States, as part of a parent-to parent support program [102].

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore deaf adults’ experiences of childhood communication access and adult mental health. Authors RM and RA are members of the deaf community, providing the project with cultural capital as well as authentic engagement with participants [103]. Kusters et al. [1] advocate for deaf epistemologies (ways of knowing) and ontologies (ways of being) in which deaf people are ideally placed to collect data about their own experiences. However, some respondents may have been hesitant to discuss specific experiences with a deaf researcher given the close-knit nature of the deaf community. Involving multiple deaf interviewers in future studies of this nature could offer opportunities for participants to identify a preferred interviewer.

Participants were provided with definitions of anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation in Auslan and written English. Participants were not asked about any formal diagnosis or other clinical verification of their experiences. This may have resulted in the under or over reporting of mental health issues. However, this research aims to understand deaf individuals lived experiences and prioritise deaf ways of knowing and being. Furthermore, while recall bias is inherent given the retrospective nature of this study, we can infer the meaningful nature of the events reported by participants who are now well into their adulthood.

We note the high proportion of participants with deaf parents (6 out of 16) given that only about 3% of deaf children globally are born to deaf parents [104]. It was beyond the scope and purpose of the present study to conduct a comparison between parent and child hearing status, but this does warrant further research. The specific focus of this research resulted in a modest sample size; however, we do not make claims as to the generalisability of the research. Nonetheless, this research contributes to an important gap in understanding mental health outcomes when limitations in communication are experienced.

This study highlights the proximal and distal stressors which result from less-than-optimal childhood communication access for deaf sign language users, demonstrating the enduring impact of early-life adversities on mental health in adulthood. The results of this research point to the need for targeted interventions and culturally safe mental health practices for signing deaf people to mitigate the long-term consequences of these stressors. Future endeavours should focus on addressing the specific factors which contribute to these inequities and means to foster inclusive environments and improve access to mental health services. Such efforts are critical to promoting equitable mental health outcomes and enhancing the overall well-being of signing deaf individuals.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

We wish to thank the 16 people who shared their experiences as part of the interview process. We would also like to thank Dr Gabrielle Hodge whose advice was pivotal in shaping the manuscript.

Finally, we thank the Auslan<>English interpreters who facilitated communication throughout the project.

not applicable.

This research was supported by a Deakin University PhD scholarship.

All activities were conducted in line with the ethical approval from Deakin University Human Ethics Research Committee (2023–078). All interview participants provided written informed consent to take part in the study which was approved by Deakin University Human Ethics Research Committee (2023–078). This research complies with the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007), for studies conducted under Australian ethical guidelines.

All participants provided written informed consent after an explanation in Auslan. Consent was obtained for their data to be included in publications, with the assurance that their names or images would not be published. All data will remain anonymous, and participants will be referred to as "Participant."

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

McRae, R., Backholer, K., Adam, R. et al. “At home, I never felt included, I always felt on the outside”: Deaf peoples’ perspectives on how inadequate access to childhood communication influences mental health outcomes. BMC Public Health 25, 2392 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23456-y