BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 2302 (2025) Cite this article

Screen-based sedentary behavior (SB) is associated with elevated BMI; however, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. This study investigates the mediating role of weight concern in the SB-BMI relationship and examines how body image perception and gender moderate this mediation. By focusing on body image as a critical contextual factor, the study aims to inform targeted interventions for adolescent obesity and overweight.

In 2016, self-report questionnaires assessing screen-based SB, weight concern, and body image perception were collected from 508 Chinese adolescents (grades 7–9), yielding 438 valid responses (response rate: 86.22%). Path analysis and bootstrap procedures with bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals were used for data analysis.

Screen-based SB was positively associated with weight concern (b = 1.115, p = 0.009) and BMI (b = 0.183, p < 0.001). The mediation analysis showed that weight concern partially mediated this relationship, with an indirect effect of 0.056 (95% CI = [0.006, 0.114]). This mediation was moderated by body image perception and gender. Specifically, the interaction between BMI overestimation and weight concern was negatively associated with BMI (b=-0.157, p = 0.011), whereas the three-way interaction of gender, weight concern, and overestimated body image perception showed a positive association with BMI (b = 0.080, p = 0.025).

Screen-based SB influences BMI, with weight concern as a mediator and body image perception and gender as moderators. These findings highlight the importance of targeting sedentary behavior and body image concerns in gender-sensitive interventions for adolescents.

Screen-based sedentary behavior (SB), such as watching TV and playing computer games, has become ubiquitous among adolescents. National surveys in the United States [1], Canada [2], and France [3] have indicated that screen-based SB accounts for a substantial proportion of waking hours in various environments. In China, approximately 34.6% of adolescents exceed the recommended daily screen time of two hours, a behavior that has been linked to adverse health outcomes [4].

Overweight and obesity are major public health issues affecting adolescent globally, particularly in developed countries [5]. Extensive evidence confirms that adolescent who spend more than two hours a day looking at screens are more likely to be overweight or obese [6, 7]. Given that screen-based SB is a modifiable behavior, understanding its association with body mass index (BMI) and its underlying mechanisms is crucial for developing effective interventions to address adolescent obesity and overweight.

The pervasive influence of weight stigma in screen media poses significant challenges for adolescents in developing a healthy body image. Body image, defined as an individual’s thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors related to their own body [8, 9], comprises two key components: weight concern and body image perception [10]. Weight concern is an individual’s preoccupation with body shape, which may manifest as a fear of weight gain, worry about body shape, and disordered eating behaviors [11]. The notion of body image perception, as implied by the term, refers to an individual’s self-assessment of body size.

Among adolescents, a strong association between body image and BMI has been observed, with notable gender differences [12,13,14]. Prolonged screen-based SB has been demonstrated to be associated with concern about body weight and to contribute to distorted body image perception [15]. Nevertheless, the relationship between screen-based sedentary behavior, body image, and BMI remains inconclusive. For instance, a study among adolescent females in Kuwait revealed no significant correlation between weight concerns, perceived body image, sedentary activities, and BMI categories [16]. In contrast, another study discovered that students exposed to prolonged screen-based SB had an increased risk of obesity and body image disturbances [17].

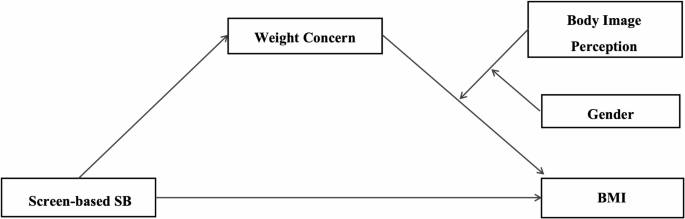

To further explore the relationship between screen-based SB and BMI in the context of body image, this study employs a moderated mediating model (see Fig. 1) to test three key hypotheses: (1) whether weight concern mediates the relationship between screen-based SB and BMI, (2) whether body image perception moderates this mediating effect, and (3) whether gender differences exist in this moderating effect. By elucidating these interrelationships, this study aims to inform more effective interventions targeting adolescent obesity and overweight through a deeper understanding of the roles of weight concern and body image perception.

This school-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in Shanghai, China, in 2016, using a random cluster sampling method. Five junior high schools were approached, and three agreed to collaborate with our research team. Students in grades 7 to 9 were invited to participate voluntarily and independently completed a comprehensive 12-item questionnaire, which covered sociodemographic information, screen-based SB, weight concern and body image perception. Following the guideline that the sample size should be ten times the number of questionnaire items [18], a minimum sample size of 120 was determined. The target sample size was adjusted to 150, accounting for a 20% non-response rate. After obtaining consent from both the adolescents and their legal guardians, 508 students were enrolled, yielding 438 valid responses (response rate: 86.2%).

Anthropometric measures

Trained researchers conducted on-site assessments using portable height and weight measurement equipment. Height was measured without shoes to the nearest 0.05 cm, and weight was measured in lightweight clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg. The BMI z-score was calculated according to the WHO Child Growth Standards [19]. In addition, Participants were classified as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese based on the National Screening Standard for Malnutrition of School-age Children and Adolescents [20] and the National Screening for Overweight and Obesity among School-age Children and Adolescents [21]. The standards were stratified by age and gender, with BMI thresholds used to define classification categories.

Screen-based sedentary behavior

Screen-based sedentary behavior was assessed using a subscale from the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) [22]. This subscale measured time spent on activities such as watching television, playing video or computer games, and using computers for non-school-related purposes. Higher scores indicated greater engagement in screen-based SB. The YRBS has demonstrated strong reliability in previous studies [23], and in this study, the subscale showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.678) [24].

Weight concern

The Weight Concerns Scale (WCS) [11] is a brief five-item measure designed to assess concerns about body weight and to identify potential precursors of eating disorder symptoms. Participants rated their responses on a Likert scale ranging from 4 to 7 points, with higher scores indicating greater weight concern [25]. In this study, the WCS demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.737).

Body image perception

Body image perception was assessed using the Collin’s Children Body Image Scale (CBIS) [26], which has been validated among Hong Kong Chinese children [27]. Participants were shown seven images and asked to select the one they believed most closely resembled their own body. Body image (mis-)perception was calculated as the difference between actual weight status and perceived body size (actual minus perceived), yielding scores ranging from + 6 (underestimation) to − 6 (overestimation) [27]. A score of zero indicated an accurate perception of body image.

Descriptive statistics were computed using R (version: 2023.06.1 + 524). Categorical variables (e.g., gender, grade, and body image perception accuracy) were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or median [interquartile range, IQR] for non-normally distributed data. Group differences across weight status categories were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Missing values were excluded from the analysis.

A moderated mediation model was constructed to examine (1) whether weight concern mediates the relationship between screen-based SB and BMI, and (2) whether body image perception and gender moderate this mediation. Screen-based SB, weight concern, and BMI z-score were treated as continuous variables, while body image perception and gender were treated as categorical variables. Path analysis was performed using the SPSS macro-PROCESS, with direct, indirect, and total effects estimated using 5,000 bootstrap samples to generate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 1 presents the distribution of sociodemographic and outcome variables across different weight status categories. Among the 438 participants, 4.3% were classified as underweight, 60.7% as normal weight, 18.7% as overweight, and 16.2% as obese. Regarding grade level, 54.1% of participants were in the 7th grade, 42.7% in the 8th grade, and 3.2% in the 9th grade. Significant differences in weight status were observed between genders (p < 0.001). Boys showed a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity compared to girls (overweight: 21.2% vs. 15.9%; obesity: 21.2% vs. 10.6%). No significant differences in screen-based sedentary behavior were found across the different weight states (F = 1.481, p = 0.108). However, weight concern and body image perception exhibited significant differences (p < 0.001).

Table 2 illustrates the correlations between the variables under investigation. Significant correlations were observed between screen-based sedentary behavior, potential mediators (e.g., weight concern), and BMI. Based on these correlations, a mediation analysis was conducted to further investigate the relationships between these variables.

PROCESS macro-Model 4 was used to examine the mediating effect of weight concern on the relationship between screen-based SB and BMI. As shown in Table 3, screen-based SB was positively associated with weight concern (b = 1.115, p = 0.009) and BMI (b = 0.183, p < 0.001). The mediation analysis indicated that weight concern partially mediated the relationship between screen-based sedentary behavior and BMI, with an indirect effect of 0.056 (95% CI = [0.006, 0.114]), in addition to the direct effect.

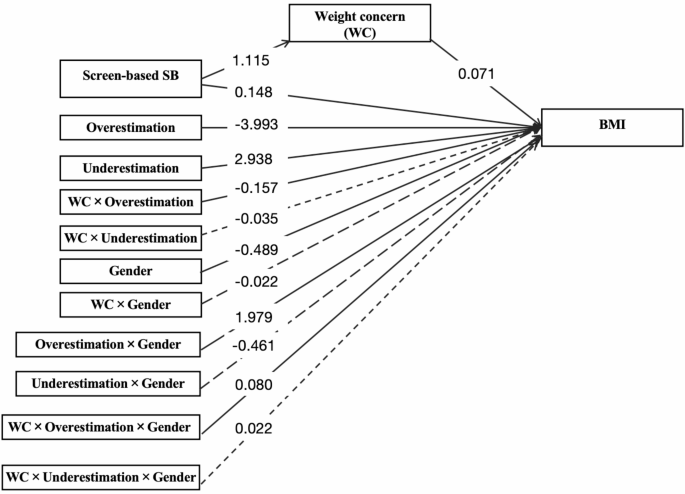

To assess the full conceptual model, a moderated mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS macro-Model 18. The results, summarized in Table 4 and illustrated in Fig. 2, demonstrated a strong model fit, with an R-squared value of 0.492 and a significant F-statistic (F = 34.229, p < 0.001), reflecting the model’s substantial explanatory power.

Consistent with prior findings, screen-based SB was positively associated with BMI, supporting the hypothesis that increased sedentary behavior may contribute to higher BMI and a greater likelihood of obesity (b = 0.148, p < 0.001). Additionally, screen-based SB influenced BMI indirectly through weight concern, conditional on the accuracy of body image perception and gender. Specifically, weight concern interacted with the overestimation of body image perception, moderating its effect on BMI (b = -0.157, p = 0.011). When gender interacted with weight concern and overestimation of body image perception, a significant positive effect on BMI was observed (b = 0.080, p = 0.025). When body image perception was accurate, the indirect effect of screen-based sedentary behavior on BMI through weight concern was stronger among males(conditional indirect effect = 0.055, 95% CI = [0.003, 0.128]. Among females, this indirect effect was slightly strengthened when body image perception was overestimated (conditional indirect effect = 0.035, 95% CI = [0.002, 0.092]).

Bootstrap results of the moderated mediation model. Note: The solid line indicates a significant path (p < 0.05), while the dashed line represents an insignificant path

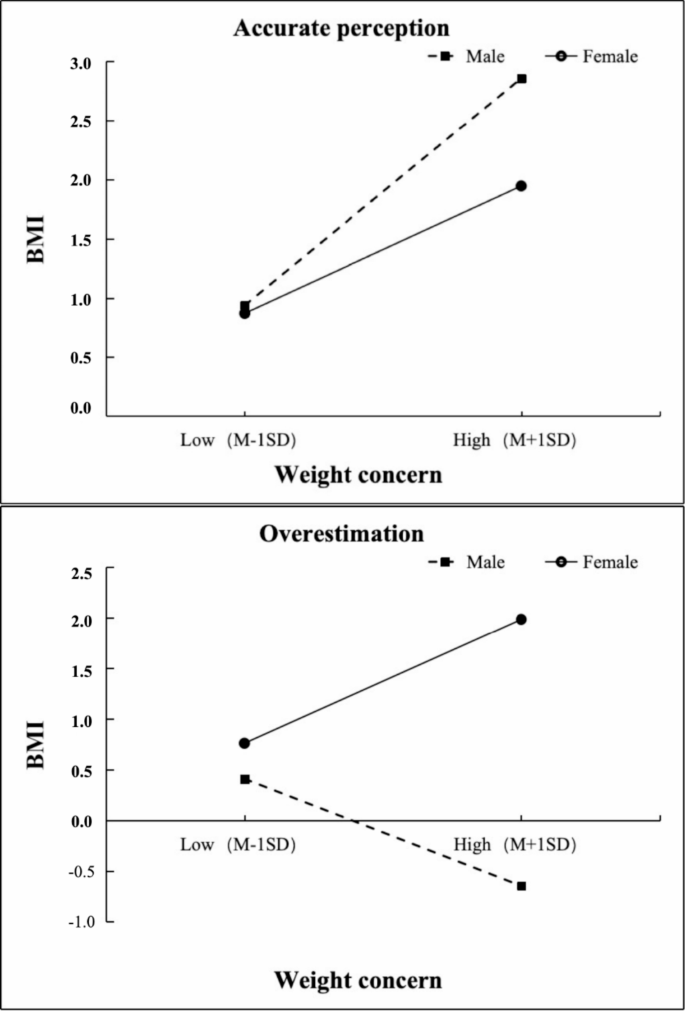

The moderator effects were further explored through a spotlight analysis conducted using the PROCESS macro. The spotlight analysis examined the three-way interaction among weight concern, body image perception, and gender on BMI (Fig. 3). An increase in weight concern was associated with a rise in BMI when individuals had an accurate body image perception, with a greater increase observed among males. Among males who overestimated their BMI, an increase in weight concern was linked to a decrease in BMI, whereas in females, a significant and substantial rise in BMI was observed.

This study aimed to explore the complex relationship between screen-based sedentary behavior and BMI from the perspective of body image, with the goal of informing more effective weight management programs for adolescents. In this sample, 34.93% of participants were classified as overweight or obesity, with a higher proportion of boys (64.05% vs. 35.95%). Similar trends have been observed in studies from other cities in China, where boys also exhibit higher rates of overweight and obesity compared to girls [28, 29].

Extensive literature has established a link between screen-based SB and negative body image outcomes, including body dissatisfaction and heightened weight concerns [30, 31]. Our results add to this literature, confirming a positive relationship between screen-based SB and weight concern among adolescents. Moreover, our study found that weight concern mediated the relationship between screen-based SB and BMI. Specifically, higher levels of screen-based SB were associated with increased weight concern, which in turn was linked to a higher BMI. Excessive weight concern can lead to anxiety, emotional distress, and body dissatisfaction, potentially contributing to the development of eating disorders [25, 32, 33]. A systematic review also supports this notion, indicating that adolescents with high body weight concerns tend to engage in unhealthy weight-related behaviors, such as binge eating, extreme dieting, and the use of weight-loss drugs [34]. Previous studies have also suggested that individuals engaging in extreme weight-control behaviors often have higher BMIs [35]. Similarly, adolescents who adopt restrictive dieting behaviors to control their weight may paradoxically experience weight gain [36]. Collectively, these findings provide insights into the reasons why heightened weight concern has a positive association with BMI.

Our study also underscores the critical role of body image perception in moderating the mediation effect. Specifically, the interaction between overestimation of body size and weight concern was negatively associated with BMI. However, among female adolescents, the combination of overestimated body image perception and weight concern was positively associated with BMI. Previous research suggests that adolescent girls are more likely to experience negative body image concerns and overestimate their body size compared to boys, which may increase their likelihood of engaging in unhealthy weight-control behaviors [30, 37]. Additionally, individuals with inaccurate weight perceptions are more likely to report extreme weight-related behaviors than those with accurate perceptions [38]. Despite highly valuing self-image, girls may also exhibit lower levels of physical activity [15], potentially amplifying the impact of negative body image concerns. These factors may contribute to the observed association between overestimated body image perception, weight concern, and higher BMI among female adolescents.

There are several limitations to this study that should be considered. First, the assessment of screen-based SB relied on subjective questionnaires, which may introduce information bias. Another limitation is that this study used data from 2016, making it challenging to establish a causal relationship between weight concern and BMI. Future longitudinal research is required to clarify the mechanisms at play, particularly in terms of temporal precedence.

Despite these limitations, it is important to highlight the strengths of this study, including the use of structural equation modeling to explore the relationship between screen-based SB and BMI from the perspective of body image. Our findings have significant practical implications, especially for the design of weight management programs targeting adolescents. Screen-based SB is associated with weight status and may also be linked to body image concerns. Therefore, efforts to reduce screen-based SB should also consider promoting a healthy body image, which may have lasting and meaningful implications for adolescent health. This is particularly important for girls, who may be more susceptible to extreme weight-related behaviors. Interventions should encourage healthy, active behaviors, such as increasing physical activity levels.

Taken together, the available evidence supports several key findings. First, screen-based sedentary behavior is significantly and positively associated with BMI. Second, weight concern functions as a mediator, indicating that the association between screen-based SB and BMI may, in part, be explained by weight concern. Finally, body image perception moderates this mediated relationship, with differences observed across gender.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- SB:

-

Sedentary Behaviors

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- BI:

-

Body Image

- WC:

-

Weight Concern

- YRBS:

-

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

- WCS:

-

Weight Concerns Scale

Thanks for Sanquan, Fengfan, and Chaoyang junior middle schools organizing the field surveys, and all investigators and participants were involved in.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [grant numbers 2022YFC3601505]; National Natural Science Foundation of China for Young Scholars [grant numbers 71603182]; Soft Science Project of the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission [grant numbers 24692113600]; Education and Scientific Research Project of Shanghai [grant numbers C2021039]; Hong Kong Polytechnic University [grant numbers 1-ZVH8]. The authors had no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the presented work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the presented work.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of Tongji University (ref: LL-2016-ZRKX-017). Written informed parental consent and student assent for participation were obtained from participants.

No applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Tan, S., Zhou, L., Abdukerima, G. et al. Screen-based sedentary behavior and BMI among Chinese adolescents: weight concern as a mediator moderated by body image perception. BMC Public Health 25, 2302 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22367-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22367-2