BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 2380 (2025) Cite this article

Female genital mutilation (FGM) remains a critical global public health challenge, with over 230 million affected women and girls, predominantly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Despite the reduction in FGM in both countries, the proportion of women who had FGM are still considerably high. Therefore, the study seeks to examine the socio-economic/demographic determinants of FGM in Kenya and Tanzania to inform more targeted interventions.

A retrospective analysis of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 6,517 women aged 15–49 in Kenya and Tanzania (2008–2022) was conducted. Trends were assessed using weighted prevalence percentages and visualized via line graphs. Chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for complex survey design, identified associations between FGM and socio-demographic, economic, and media-related determinants.

Higher education (AOR = 0.25, p < 0.001), wealth (AOR = 0.62, p < 0.002), urban residence (AOR = 0.37, p < 0.001), and weekly radio exposure (AOR = 0.53, p < 0.001) significantly reduced FGM risks. Conversely, rural residence (AOR = 4.12, p < 0.001), religious mandates (AOR = 3.81, p < 0.001), and recent internet use (AOR = 2.40, p < 0.001) increased vulnerability. Contextual disparities emerged: Kenya’s FGM was strongly associated with Muslim affiliation (AOR = 9.41, p < 0.001), while Tanzania’s persistence stemmed from rural agrarian livelihoods and occupational inequities. Internet use paradoxically correlated with higher FGM prevalence, reflecting potential urban-rural divides in digital health messaging efficacy.

Education, economic stability, urban living, literacy, and radio exposure lower FGM risks in Kenya and Tanzania, while rural poverty, limited education, religious justifications, and internet use increase them. FGM in Kenya is linked to Muslim practices, requiring faith-sensitive strategies, while in Tanzania, it is tied to rural ethnic traditions. Interestingly, higher internet use correlates with increased FGM prevalence, suggesting it may perpetuate harmful norms without targeted messaging. Effective interventions should integrate legal enforcement, community education, women’s empowerment, and cultural partnerships, extending urban strategies to rural areas and combating misinformation through digital literacy. Limitations like cross-sectional design highlight the need for longitudinal research. Ongoing, context-driven efforts are crucial for eliminating FGM and advancing global gender equity.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as all procedures involving partial or total removal of external genitalia or injury to female genital organs for non-medical reasons [1]. It remains a critical global public health and human rights challenge. Over 230 million women and girls worldwide have undergone FGM, with Sub-Saharan Africa bearing the highest burden (144 million cases) [2, 3]. The WHO classifies FGM into four types, ranging from clitoridectomy (Type I) to infibulation (Type III) and symbolic nicking (Type IV) [1]. Immediate complications include severe pain, hemorrhage, and infections, while long-term consequences encompass chronic pain, obstetric risks like perineal tears, neonatal mortality, and psychological trauma [1, 4,5,6]. Despite international condemnation, FGM persists due to deeply rooted cultural norms, perceived religious obligations, and economic incentives, such as dowry negotiations and financial gains for practitioners [1, 7, 8]. Alarmingly, healthcare providers increasingly perform medicalized FGM, driven by misconceptions of safety and profit, further complicating eradication efforts [9, 10].

In East Africa, FGM prevalence varies significantly across countries and communities. Kenya reports a decline from 27.9% (2008/09) to 16.0% (2022), while Tanzania shows a reduction from 17.6% (2010) to 8.9% (2022) [11, 12]. In contrast, Uganda has low prevalence (0.2%) but high awareness (50%) [13]. The practice is often perpetuated as a social norm, particularly among ethnic groups like the Maasai in Tanzania and Somali communities in Kenya, where FGM is viewed as a rite of passage ensuring marriageability and cultural identity [14, 15]. Economic motivations also play a role: traditional circumcisers profit directly, while families may secure higher bride prices [7, 16]. Migration patterns have further globalized FGM, with diaspora communities in Europe and North America continuing the practice clandestinely [3, 17].

While existing studies emphasize sociocultural drivers of female genital mutilation (FGM) [18, 19], Critical gaps remain in understanding the interplay of socioeconomic and demographic factors among women of reproductive age. For instance, research in Nigeria highlights education as a protective factor [20], Ethiopian studies link wealth to reduced FGM prevalence [21]. However, comprehensive comparative analyses focusing on East African countries like Kenya and Tanzania, particularly using Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data across multiple periods, are limited. Despite a reduction in FGM prevalence between 2008 and 2022, the proportion of women affected remains considerably high in both countries. Therefore, this study seeks to examine and compare the socioeconomic and demographic determinants of FGM among women of reproductive age in Kenya and Tanzania to inform more targeted interventions. Kenya and Tanzania were selected due to their contrasting FGM trajectories, robust anti-FGM legislation, and availability of recent DHS data (2022). Although Kenya’s 2011 Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act and Tanzania’s 1998 Sexual Offenses Act criminalize FGM, enforcement remains inconsistent, particularly in rural and ethnic communities where traditional norms continue to challenge legal frameworks [16, 18].

This study leverages nationally representative DHS data from 6,517 women aged 15–49 in Kenya and Tanzania (2008–2022) to analyze trends and determinants. Employing a retrospective cross-sectional design, it examines socio-demographic, economic, and media-related factors to inform targeted interventions to accelerate progress toward eliminating FGM in culturally diverse settings.

This study utilized a retrospective cross-sectional design, analyzing data from the DHS conducted between 2008 and 2022 in Tanzania and Kenya. These countries were selected due to their recent availability of DHS data in 2022 and significant policy interventions to reduce FGM prevalence. By focusing on women aged 15–49, the study aims to identify key patterns and predictors of FGM practices, contributing to the understanding of the socio-cultural and health implications associated with FGM. The retrospective nature of the analysis facilitates the examination of temporal changes in FGM practices alongside associated socio-demographic factors, enhancing insights into the dynamics of FGM prevalence in these countries over time.

The study focuses on Kenya and Tanzania, two East African nations with recent DHS data (2022), and shared cultural contexts that influence FGM practices. Both countries have implemented policy measures to combat FGM, making them ideal for comparative analysis. The interconnectedness of these nations within the East African region underscores the importance of understanding FGM trends and their public health implications.

The study included 6,517 women aged 15–49 years from the 2022 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in Kenya (N = 4,488) and Tanzania (N = 2,033) for determinants analysis. Datasets spanning 2008–2022 were utilized to assess temporal trends in FGM prevalence.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was FGM status, defined as a binary measure (Yes = 1/No = 0) indicating if a woman underwent any form of FGM. Women were coded as “Yes” (1) if they reported genital nicking, removal, or infibulation for themselves. “No” (0) indicated the respondent had no history of FGM. Responses were derived from DHS questions on personal experience and daughters’ circumcision status, consolidating all FGM types into a single binary outcome.

Explanatory variables

The study identified interplay determinants of FGM prevalence by harmonizing variables from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) datasets across Kenya and Tanzania (2008–2022). Variables were selected based on theoretical relevance to socio-ecological frameworks and their potential interactions in influencing FGM practices. Data integration involved merging multi-phase DHS datasets while ensuring temporal and cross-country consistency. Key variables underwent systematic coding and recoding to align with study objectives, with coding and recoding found in Table 1. Socio-demographic factors: Age (recoded into 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–49), education (none, primary, secondary, higher), marital status (married/living with partner), literacy (categorized as unable to read, partial reading, full reading), occupation (agricultural, skilled/unskilled labor, domestic work), and wealth index (poor, middle, rich, derived from DHS asset-based quintiles). Environmental factors: Urban/rural residence, standardized across surveys. Women-specific factors: Age at circumcision (ordinal: <5, 5–9, 9–14, 15–19), daughters’ circumcision status (none, 1, 2, ≥ 3), perception of FGM continuation (continue/stop/depends), awareness of FGM (yes/no), and religious justification (yes/no/don’t know). Media exposure: Newspaper, radio, TV, and internet use frequencies (recoded as none, less than weekly, weekly).

The study includes women aged 15–49 who participated in the DHS surveys (2008–2022) in Tanzania and Kenya. Data from countries with a history of DHS data collection and relevant FGM-related measurements were considered. To ensure data integrity, incomplete or missing responses related to FGM status were excluded from the analysis.

Sampling techniques

The DHS employs a two-stage cluster sampling design:

Key components of the sampling design include the Primary Sampling Unit (PSU), identified by variable V021; strata, defined by variable V022; and weighting, applied using variable D005 to ensure representativeness. Two datasets were used: one for trend analysis (merged data from Kenya and Tanzania, 2008–2022) and another for determinants analysis (combined data from Kenya and Tanzania, 2022). Weights were applied using DHS survey weighting variables (D005) to adjust for sample design and nonresponse bias. All analyses accounted for DHS’s complex survey design, including stratification (variable V022), clustering (V021), and weighting (D005/1,000,000) to ensure nationally representative estimates.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26. The dataset underwent preprocessing, including cleaning, recoding, and weighting (d005/1,000,000) to account for sampling biases. Complex sampling techniques were applied to ensure representativeness. The relationships between FGM prevalence and socio-demographic factors were assessed using Chi-square tests (p < 0.05), Trends in FGM prevalence were analyzed using line graphs, and the determinants of FGM were identified using weighted Multivariate binary logistic regression. Multicollinearity was addressed using a correlation matrix, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and composite indices. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and results were reported as odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values (significance level: 0.05). To assess interplay, variables were cross-validated for consistency, with missing data addressed through listwise deletion.

This study utilized publicly available, de-identified data from the MEASURE DHS program, including the Tanzania and Kenya DHS. The respective Ministries of Health in Tanzania and Kenya obtained ethical approval and participant consent during the original data collection. MEASURE DHS and the ICF Institutional Review Board secured written permission to access and analyze the data.

Table 1 presents the sample’s sociodemographic, women, media, and environmental characteristics (N = 6,517 women of reproductive age). Age distribution was skewed toward younger cohorts, with 42.6% aged 25–34 and 22.1% aged 15–24. Educational attainment showed that 48.5% of women and 55.9% of their husbands completed primary education, while 10.4% of women and 12.8% of their husbands attained higher education. Households were predominantly male-headed (94.1%). Employment disparities were evident: 43.6% of husbands worked as skilled laborers, while 56.5% of women were non-working or engaged in domestic tasks. Economic stratification revealed 41.8% of households were classified as “rich” and 38.2% as “poor.” Most women were married (88.5%), and 74.0% demonstrated literacy. Attitudes toward female genital mutilation (FGM) were strongly oppositional: 98.0% advocated discontinuation, 99.3% reported not circumcising daughters, and 94.9% rejected religious justification. Media exposure varied: 54.8% listened to the radio weekly, 43.9% watched TV weekly, and 57.7% never used the internet. Geographically, 68.8% resided in Kenya and 66.3% in rural areas.

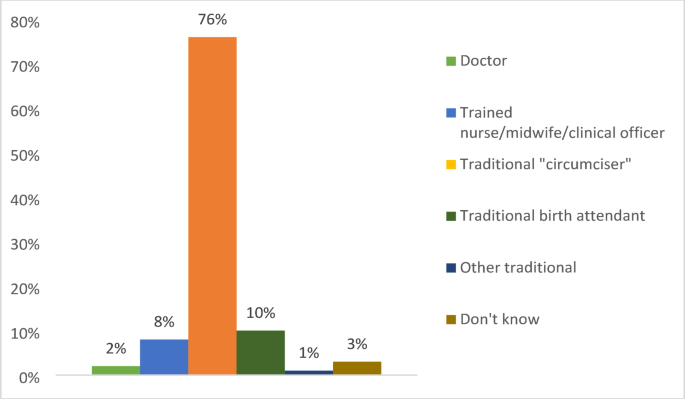

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of female genital mutilation (FGM) cases by practitioner type. Traditional circumcisers performed the majority of procedures (75%), followed by health professionals (18%) and informal providers (7%).

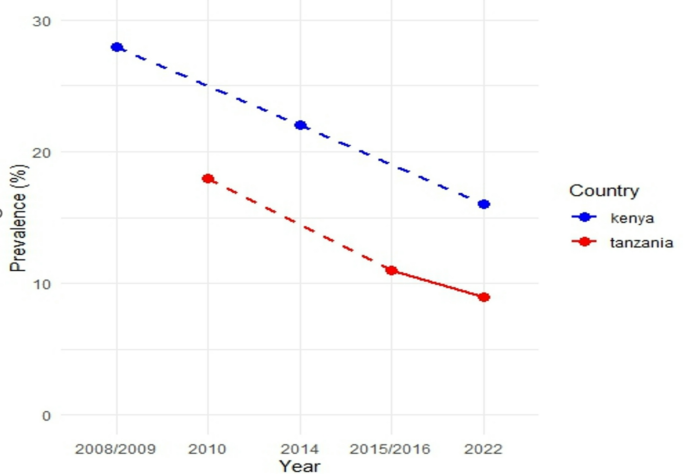

Table 2 presents data on the prevalence Trends of FGM among women of reproductive age in Kenya and Tanzania across different survey years. The table includes the total number of weighted women surveyed, the number of women with FGM, and the corresponding weighted FGM prevalence (%) for each year. In Kenya, FGM prevalence has shown a consistent decline over the years. In 2008/2009, the prevalence was 28% among 1,309 surveyed women, which decreased to 22% in 2014 with a larger sample size of 4,635 women. By 2022, the prevalence had dropped to 16% among 4,484 surveyed women, indicating a sustained reduction in the practice. Similarly, in Tanzania, FGM prevalence has also declined over time. In 2010, the prevalence was 18% among 839 surveyed women. By 2015/2016, the prevalence had fallen 11% among 1,197 women. In 2022, the prevalence further decreased to 9% among 2,033 surveyed women, reflecting continued progress in reducing FGM practices in the country.

Figure 2 shows the line graph displaying FGM prevalence Trends from 2008 to 2022, with the X-axis representing the phases of FGM in different years. Phase I comprises the years 2008/2009 and 2010 for Kenya and Tanzania. Phase II shall consist of 2014 and 2015/2016 for Kenya and Tanzania, and Phase III comprises the year 2022 for Kenya and Tanzania, respectively. The Y-axis shows the weighted prevalence percentage. It features separate lines for Tanzania and Kenya, allowing for a visual comparison of trends in FGM prevalence over the specified period.

Table 3 presents adjusted odds ratios (AORs) from a multivariable logistic regression analysis identifying predictors of female genital mutilation (FGM) among Tanzanian women (N = 2,033, 2022). Older age was strongly associated with FGM, with women aged 25–34 (AOR = 1.97, 95% CI:1.27–3.06, p = 0.003) and 35–44 (AOR = 2.16, 95% CI:1.36–3.45, p = 0.001) exhibiting significantly higher odds compared to those aged 15–24. Rural residence emerged as a key predictor (AOR = 4.12, 95% CI:2.08–8.13, p < 0.001), aligning with Table 4’s descriptive findings of disproportionately high Rural FGM prevalence (93.3% vs. 69.3%). Socioeconomic and occupational disparities persisted: agricultural workers had elevated odds (AOR = 1.74, 95% CI:1.17–2.60, p = 0.007).

Consistent with Table 4’s higher FGM prevalence in this group (46.1% vs. 26.1%). Lower media/technology engagement, a risk factor in Table 4, was partially reflected in regression results; weekly radio listeners had higher odds (AOR = 1.52, 95% CI:1.00–2.31, p = 0.048), while recent internet users paradoxically showed increased odds (AOR = 1.50, 95% CI:1.18–1.92, p = 0.001), potentially reflecting confounding or non-health-related usage. Formal education (AOR = 0.56, p = 0.078) and full literacy (AOR = 0.51, 95% CI:0.34–0.75, p = 0.001) were protective, corroborating Table 4’s inverse association between education/literacy and FGM. Notably, women aware of FGM had 49% lower odds (AOR = 0.51, 95% CI:0.36–0.74, p < 0.001).

Tables 5 and 6 present descriptive and multivariable logistic regression analyses of factors associated with female genital mutilation (FGM) among Kenyan women respectively (N = 4,488; circumcised: n = 719, non-circumcised: n = 3,769, 2022). Descriptive results (Table 5) reveal significant sociodemographic disparities: circumcised women were more likely to reside in rural areas (51.9% vs. 32.9%; p < 0.001), lack formal education (35.4% vs. 5.1%; p < 0.001), report no media exposure (91.5% never read newspapers vs. 83.3%; p < 0.001), and identify as Muslim (56.4% vs. 2.8%; p < 0.001). Regression analysis (Table 6) identified key predictors: Muslim women exhibited 9.4 times higher odds of FGM (AOR = 9.41, 95% CI:7.54–11.76; p < 0.001) compared to Christians, aligning with Table 5’s stark religious disparity. Urban residence was protective (AOR = 0.35, 95% CI:0.26–0.47; p < 0.001), contrasting with Table 6’s rural predominance, suggesting urbanization may mitigate FGM through access to education or anti-FGM campaigns. Formal education (AOR = 0.38, 95% CI:0.23–0.63; p < 0.001) and partial literacy (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI:0.34–0.89; p = 0.015) reduced odds, consistent with Table 5’s lower FGM prevalence among educated women (64.6% vs. 94.9%). Occupational patterns diverged: agricultural workers had 75% lower odds (AOR = 0.25, 95% CI:0.16–0.38; p < 0.001), while non-working women (62.0% in Table 5) showed elevated risk, underscoring economic vulnerability. Media engagement played a nuanced role: frequent radio listeners had 55% lower odds (AOR = 0.45, 95% CI:0.35–0.58; p < 0.001), aligning with Table 5’s lower radio use among circumcised women (36.5% vs. 69.9%). Paradoxically, recent internet users had higher odds (AOR = 1.52, 95% CI:1.17–1.98; p = 0.002), potentially reflecting confounding (non-health-related usage). Marital cohabitation was protective (AOR = 0.39, 95% CI:0.27–0.58; p < 0.001), contrasting with Table 5’s higher FGM prevalence among married women (94.6% vs. 87.3%), suggesting traditional marital norms may perpetuate FGM. Non-significant age and sex-of-household-head associations (p > 0.05) imply that cultural or intergenerational drivers outweigh individual demographics. These findings emphasize religion, education, and rural-urban inequities as critical determinants, advocating for faith-sensitive interventions and media literacy programs. Methodological limitations, such as overlapping media variable categorizations, warrant refinement to isolate behavioral pathways.

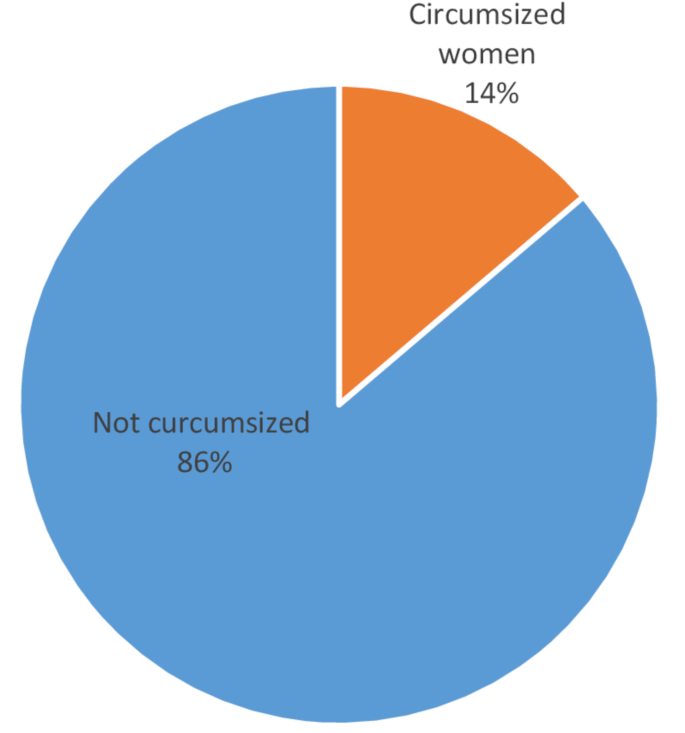

Table 7 highlights the significant socio-demographic, media, and environmental factors influencing FGM prevalence. As shown in Figs. 3 and 14% of women are circumcised, while 86% remain uncircumcised, based on a weighted sample of 6,517 women.

Education emerged as a critical determinant of FGM. Women with no formal education had the highest circumcision rate (35.2%), while those with higher education had the lowest (6.1%) (p < 0.001). Similarly, women whose husbands had no education were more likely to be circumcised (25.4%) compared to those whose husbands attained higher education (9.4%) (p < 0.001).

Occupational status significantly influenced FGM prevalence. Women who were unemployed or engaged in household domestic work had a circumcision rate of 69.8%, compared to only 10.5% among skilled workers (p < 0.001). Wealth status also played a role, with poorer women showing a higher circumcision rate (48.8%) compared to wealthier women (36.9%) (p < 0.001).

Literacy was another key factor, with 38% of circumcised women unable to read at all, compared to only 10.8% of non-circumcised women (p < 0.001). The presence of circumcised daughters in a household was significantly higher among circumcised women, with 4.2% reporting at least one circumcised daughter, compared to only 0.2% among non-circumcised women (p < 0.001).

Perceptions about FGM also varied significantly. While the majority of both groups believed the practice should be stopped, a slightly higher proportion of circumcised women (1.6%) supported its continuation compared to non-circumcised women (1.0%) (p = 0.006). Additionally, 19.1% of circumcised women believed FGM was a religious requirement, in contrast to only 2.1% of non-circumcised women (p < 0.001).

Media exposure was significantly associated with FGM. Women who did not read newspapers at all had a higher circumcision rate (90.3%) compared to those who read at least once a week (3.9%) (p < 0.001). Similarly, 50.6% of circumcised women never listened to the radio, compared to only 25.3% of non-circumcised women (p < 0.001). Television exposure followed the same trend, with 57.6% of circumcised women never watching TV, versus 42.8% of non-circumcised women (p < 0.001).

Place of residence significantly influenced FGM prevalence, with 42.9% of urban women being circumcised compared to 57.1% of rural women (p < 0.001).

Table 8 presents the results from Multivariate logistic regression examining the determinants of FGM prevalence among women of reproductive age in Tanzania and Kenya. The dependent variable, FGM status, was binary (0 = no, 1 = yes). The analysis included crude odds ratios (COR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. The findings are organized into thematic categories for clarity.

Significant associations were observed between FGM prevalence and socio-demographic characteristics. Women with higher educational attainment had significantly lower odds of FGM (primary education: AOR = 0.639, 95% CI = 0.497–0.82; higher education: AOR = 0.249, 95% CI = 0.155–0.399; p < 0.001). Similarly, women from wealthier households were less likely to undergo FGM (middle wealth: AOR = 0.733, 95% CI = 0.57–0.943; rich: AOR = 0.624, 95% CI = 0.461–0.845; p < 0.05). Rural residence was also associated with higher odds of FGM than urban areas (AOR = 0.369, 95% CI = 0.293–0.466; p < 0.001). No significant associations were found for participant age or sex of household head (p > 0.05).

Women who reported that FGM was required by religion had significantly higher odds of undergoing FGM (AOR = 3.812, 95% CI = 2.813–5.165; p < 0.001). Additionally, women who had heard of FGM were less likely to undergo the practice (AOR = 0.536, 95% CI = 0.414–0.693; p < 0.001).

Media exposure was inversely associated with FGM prevalence. Women who listened to the radio at least once a week had lower odds of FGM (AOR = 0.526, 95% CI = 0.432–0.64; p < 0.001). However, the frequency of watching television and reading newspapers showed no significant association in the adjusted model (p > 0.05). Internet use in the last 12 months was associated with higher odds of FGM (AOR = 2.395, 95% CI = 1.911–3.001; p < 0.001).

Women engaged in unskilled work had lower odds of FGM compared to those not working (AOR = 0.665, 95% CI = 0.54–0.819; p < 0.001). Higher literacy levels were also associated with reduced odds of FGM (able to read whole sentences: AOR = 0.451, 95% CI = 0.348–0.584; p < 0.001).

Women who believed that FGM should be stopped showed no significant difference in FGM prevalence compared to those who believed it should continue (p > 0.05). However, awareness of FGM was a protective factor, with women who had heard of FGM being less likely to undergo the practice (AOR = 0.536, 95% CI = 0.414–0.693; p < 0.001).

This study examines the socio-economic, cultural, and demographic determinants of female genital mutilation (FGM) among women of reproductive age in Tanzania and Kenya, contextualizing key factors within existing literature to explore their implications for eradication efforts. By analyzing nationally representative data from 2008 to 2022, the research identifies structural drivers and protective influences that shape FGM prevalence in these East African nations. The findings align with global strategies to combat FGM through education, legal frameworks, and community engagement, while underscoring the urgency of addressing persistent socio-cultural norms and systemic inequities. Below, we delve into the interplay of factors sustaining FGM practices and their implications for designing targeted interventions.

Our analysis identifies rural residence as a key predictor of FGM/C, consistent with studies linking rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa to entrenched traditions due to limited health education and gender equity policies [22, 23]. This geographic disparity is exacerbated by poverty, as circumcised women were disproportionately poor and employed in agriculture, reflecting broader patterns where economic precarity reinforces cultural conformity [24]. While education showed potential as a protective factor, it highlights no significance systemic barriers like underfunded rural schools and persistent gender inequities [25, 26].

Media exposure yielded mixed outcomes: limited internet and television access underscored inequities, while radio use was paradoxically linked to higher risk, likely due to programming reinforcing harmful norms [27]. Age and marital status further shaped vulnerability, with older women and cohabiting individuals facing elevated risk, aligning with evidence on generational norms and autonomy deficits in informal unions [28, 29]. Conversely, FGM/C awareness and literacy reduced risk, emphasizing education’s role in empowering women to resist harmful practices [30]. However, gaps in rural awareness campaigns reveal systemic failures in outreach [23, 31].

Effective interventions must address Tanzania’s intersecting inequities through economic empowerment, literacy programs, and community-led strategies, as demonstrated in African success stories. Prioritizing rural areas where deprivation and tradition intersect and engaging local leaders are critical to disrupting cycles of harm.

Muslim affiliation strongly correlates with higher FGM prevalence in Kenya, consistent with studies emphasizing the role of religious and cultural norms, particularly in East Africa [32]. A 2021 Kenyan study noted that religious leaders in Muslim-majority areas often promote FGM as a marital rite of passage, sustaining the practice despite legal bans [32]. This highlights the importance of faith-sensitive approaches, such as engaging religious leaders to reshape FGM narratives without alienating the community [33].

Urban residence was protective, reflecting greater exposure to anti-FGM messaging and legal enforcement [34]. A 2023 KDHS-based analysis linked urban living to higher female school enrollment, associated with delayed marriage and lower FGM risk [12]. In contrast, rural prevalence reflects barriers like poor education and healthcare access, as seen in a 2020 Samburu County study [35].

Formal education and partial literacy were protective, echoing UNICEF’s 2024 report that educated women are less likely to support FGM due to awareness of its health and legal risks [36]. Frequent radio use lowered the odds, aligning with a 2019 evaluation of Kenya’s “Let’s End FGM” campaign, which cut community support by 40% in target areas [27]. Paradoxically, recent internet use increased odds, possibly due to digital inequality and limited health content exposure among low-income users [37, 38].

Women engaged in agriculture had lower odds of supporting female genital mutilation (FGM) than non-working women, supporting research that links agricultural work to greater economic autonomy and reduced reliance on FGM for social acceptance [39]. Similarly, cohabiting women were less likely to support FGM than married women, suggesting that traditional marriage norms may reinforce FGM practices, as highlighted by the study of Socio-economic and demographic determinants of female genital mutilation in sub-Saharan Africa [39].

The prevalence and drivers of female genital mutilation (FGM) in Tanzania and Kenya reveal critical contrasts shaped by sociocultural, economic, and geographic contexts. In Tanzania, FGM is disproportionately concentrated in rural areas, reflecting entrenched traditional practices and limited access to education and healthcare services [22, 40]. This rural clustering aligns with studies linking geographic isolation to the persistence of FGM, as rural communities often rely on cultural norms to maintain social cohesion [41]. Conversely, in Kenya, while rural regions also exhibit high FGM prevalence, urban residence emerges as a protective factor, likely due to greater exposure to anti-FGM campaigns and legal enforcement [42,43,44,45].

Religion plays a divergent role in Kenya, FGM is strongly associated with Muslim communities, where cultural practices tied to Islamic marital rites perpetuate the tradition [45]. In contrast, Tanzanian FGM practices are less influenced by religion and more deeply rooted in ethnic traditions, particularly among rural ethnic groups where FGM is viewed as a rite of passage [45].

Education serves as a protective factor in both countries but operates differently. In Kenya, formal education significantly reduces FGM risk, likely by increasing awareness of health and legal repercussions [46]. In Tanzania, however, rural-urban disparities in educational access exacerbate vulnerabilities, with uneducated rural women facing heightened FGM risks due to systemic marginalization [47].

Economic drivers further differentiate the two nations. In Tanzania, rural women engaged in agriculture are disproportionately affected, as agrarian communities often perpetuate FGM to uphold traditional gender roles [48]. In Kenya, agricultural work paradoxically reduces FGM risk, possibly due to economic empowerment from female land ownership and participation in cooperatives [46].

Media and technology exhibit mixed impacts. In Tanzania, limited media access in rural areas correlates with FGM persistence, whereas in Kenya, frequent radio listeners show lower FGM engagement, underscoring radio’s effectiveness in disseminating anti-FGM messaging [43]. Both countries, however, report paradoxical links between internet use and FGM, suggesting that digital access alone cannot counter cultural norms without targeted health communication [49].

Socio-economic determinants: education and wealth

Our findings underscore education as a critical protective factor against FGM. Women with higher education (AOR = 0.249, p < 0.001) exhibited markedly lower odds of undergoing FGM compared to those without formal education. This mirrors evidence from Ethiopia, where educated women are more likely to reject FGM due to increased awareness of health risks and legal repercussions [50]. Education fosters critical thinking and access to health information, empowering women to challenge cultural norms [51]. Similarly, wealthier households (AOR = 0.624, p = 0.002) demonstrated reduced FGM prevalence, consistent with studies in Chad, where economic stability enables families to prioritize health over tradition [52]. Affluence often correlates with urbanization, improved healthcare access, and exposure to anti-FGM campaigns, which collectively diminish reliance on harmful practices [53].

Media exposure: dual roles of information and misinformation

Media engagement, particularly internet use (AOR = 2.395, p < 0.001), was paradoxically associated with higher FGM prevalence. While digital platforms can disseminate anti-FGM messaging, their misuse to reinforce traditional norms or spread misinformation common in tightly knit rural communities may explain this trend [54]. Conversely, frequent radio listening (AOR = 0.526, p < 0.001) and television exposure (AOR = 0.369, p < 0.001) correlated with lower FGM rates, echoing findings from Nigeria, where mass media campaigns effectively shifted public opinion [33]. This dichotomy highlights the need for targeted digital literacy programs to counteract misinformation while leveraging traditional media for awareness.

Urban-rural disparities and cultural persistence

Urban residence (AOR = 0.633, p < 0.001) significantly reduced FGM likelihood, reflecting Kenya’s and Tanzania’s urban-centric policy implementations and greater access to education [55]. In contrast, rural regions, where cultural adherence remains strong, exhibited higher prevalence. For instance, 76.3% of procedures were performed by traditional circumcisers, perpetuating intergenerational cycles. Similar patterns are observed in Sudan, where deep-rooted beliefs sustain FGM despite legal bans [56]. Religious misperceptions further entrenched the practice; women believing FGM was religiously mandated had 3.8-fold higher odds (p < 0.001) of undergoing it, akin to findings among Bohra Muslims in India [57]. These results emphasize the need for faith leader engagement to disentangle FGM from spiritual identity.

Declining trends: policy and advocacy impact

The observed decline aligns with national efforts, such as Kenya’s Anti-FGM Act (2011) and Tanzania’s Law of Marriage Act (2016), which criminalize FGM while promoting community education [58, 59]. Comparable reductions in Egypt and Burkina Faso highlight the efficacy of integrating legal deterrence with grassroots advocacy [60]. However, persistent pockets of high prevalence, particularly in Kenya’s North Eastern region, signal the need for hyper-local interventions addressing economic incentives for practitioners and dowry systems that valorize FGM [61, 62].

While this study benefits from nationally representative data, its cross-sectional design limits causal inference. Self-reported FGM status may be underreported due to stigma, and merging datasets across years risks methodological inconsistencies. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to assess intervention sustainability and qualitative methods to explore nuanced cultural drivers.

This study identifies education, economic stability, urban residence, literacy, and radio exposure as key protective factors against FGM in Kenya and Tanzania, while rural poverty, limited education, religious justifications, and internet use heighten risks. Contextual disparities emerge: Kenya’s FGM is closely tied to Muslim practices, requiring faith-sensitive engagement, whereas Tanzania’s persistence stems from rural ethnic traditions and agrarian livelihoods. Paradoxically, internet use correlates with higher FGM prevalence, suggesting digital platforms may propagate harmful norms without targeted health messaging. Interventions must prioritize multi-sectoral strategies, including legal enforcement, community education, women’s economic empowerment, and collaborations with cultural/religious leaders. Urban-centric policies and radio campaigns should expand to underserved rural areas, complemented by digital literacy programs to counter misinformation. Study limitations, such as cross-sectional design and potential underreporting, highlight the need for longitudinal and qualitative research. Sustained, context-specific efforts are vital to eliminate FGM, advancing global goals for gender equity and human rights.

Access to the datasets generated and analyzed in this study is restricted due to considerations related to privacy, policy, and governance. These datasets are not publicly available; however, they may be accessed upon reasonable request through the corresponding author. Access will be granted in alignment with the ethical guidelines and institutional policies governing the study.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Library of Southern Medical University for its invaluable support in facilitating access to critical literature and resources essential for this research.

This research was funded by Special Innovation Project of General Universities in Guangdong Province in 2024 (2024 WTSCX039); The Quang Dong Province self-funded science fund project in 2024 (2024 A1515010761); General Project of Philosophy and Social Science Planning of Quang Dong Province in 2023 (GD23CGL09); Project of Educational Science Planning of Guangdong Province in 2024 (No.: 2024 GXJK114).

The study analyzed the collected data from the Demographic Health Survey (DHS), which had already obtained ethical clearance; hence, this study did not need another ethical clearance. However, permission to use the data was requested from the DHS custodian. Procedures and questionnaires for standard DHS surveys have been reviewed and approved by ICF Institutional Review Board (IRB). Additionally, country-specific DHS survey protocols are reviewed by the ICF IRB and typically by an IRB in the host country. ICF IRB ensures that the survey complies with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for protecting human subjects (45 CFR 46), while the host country IRB ensures that the survey complies with the laws and norms of the nation.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Kisendi, D.D., Lyakurwa, D., Paulo, H.A. et al. Trends and determinants of female genital mutilation prevalence among women of reproductive age in Tanzania and Kenya: a demographic and health survey analysis (2008–2022). BMC Public Health 25, 2380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23519-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23519-0