Cameras Weren’t Built For Black Skin: The Racist Roots of Photography’s Exposure Bias

Have you ever looked at your picture and wondered why your skin looks all ashy and dull? Your face appears to lack details, looking ashy but your light-skinned friend’s face has that clarity and warmth you both possess in reality. Safe to tell you that it was never bad lighting or your skin but rather a racial bias that was inbuilt in camera films.

For decades, camera films were designed to bring out the best in white skin, completely ignoring black skin or skin tones closer to the black shade. Black skin was never the priority in camera technology.

In the 1950s through to around 1980s, camera colour film technology dominated by Kodak developed films around lighter, Caucasian skin tones and this resulted in Black and Brown skin being underexposed, flat and lacking nuance.

Yes, you are right: the reason why your black skin wasn’t shining in photos is because it was never built for you.

Let’s go down the historical lane a bit.

The Shirley Standard: Whiteness as a Norm

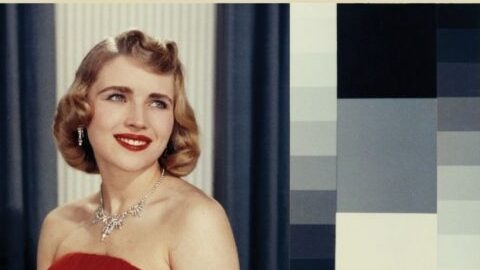

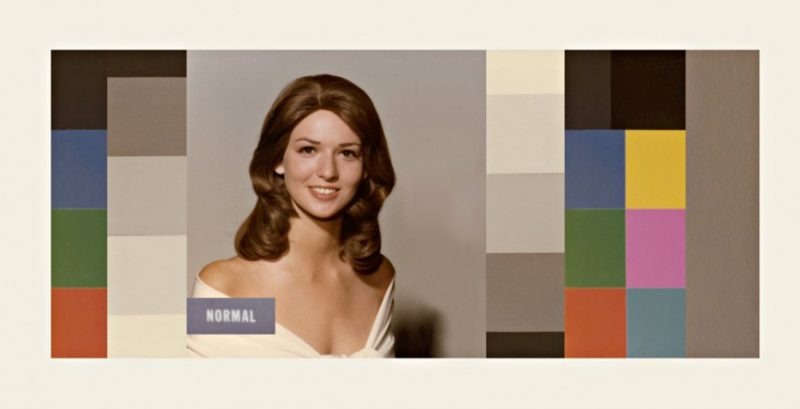

To understand how photography became biased, we need to understand how “normal” was defined. Camera manufacturers did not guess what proper exposure should look like; they relied on reference images. These images were known as Shirley cards, and they were used to standardise colour balance and exposure during film processing.

The problem was simple and devastating: Shirley was almost always white.

These reference cards featured white women with light skin, carefully styled and evenly lit. When technicians adjusted film to make Shirley look “right,” the film was considered balanced and ready for mass use. No similar effort was made to ensure Black skin looked accurate, detailed, or alive.

This meant that whiteness became the silent benchmark. Any skin tone that did not fall within that narrow range became a technical afterthought. Black skin was not invisible because it could not be captured, but because it was never the focus of calibration.

What made this standard particularly harmful was how long it went unquestioned. For decades, the industry treated these practices as neutral and purely technical, ignoring the social implications. By the time concerns were raised, the damage had already been normalised across generations of photographs.

Visible Harm: Erasure in Everyday Life

This bias did not exist in theory alone; it showed up in everyday life. Family photographs, school portraits, wedding pictures, and studio shots repeatedly failed to capture Black skin properly. Faces appeared darker than they should, details disappeared into shadows, and expressions lost depth.

Over time, this repeated misrepresentation became normalised. Black people grew accustomed to seeing themselves poorly rendered in photos and internalised the idea that this was unavoidable.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

The camera, often seen as an objective tool, quietly reinforced inequality by deciding who looked clear and who did not.

This erasure also affected how Black beauty was perceived. When cameras consistently failed to capture darker skin well, it reinforced harmful ideas about what was photogenic, professional, or desirable. These visual biases spilled into advertising, media, and fashion, shaping public perception far beyond the photograph itself.

Although minimal updates came slowly but ironically, it was not from civil rights pressures alone. In the 1970s, companies selling chocolates, dark furniture and wood tones complained about inaccurate browns. This made Kodak go back to their drawing board to make improved emulsions like Gold Max film and eventually multiracial cards.

The Digital Legacy

When photography moved from film to digital, many assumed the problem would disappear. But technology does not reset itself; it carries its past forward. Early digital cameras inherited the same assumptions that shaped film technology.

Automatic exposure systems and image-processing software were trained on limited datasets that still prioritised lighter skin tones. As a result, darker skin was often treated as shadow or background, leading to overexposed highlights and crushed details.

Even today, these remnants exist in facial recognition systems and most smartphone cameras, proving that bias can survive technological advancement if it is not intentionally addressed.

Progress Today: Rebuilding for Equity

In recent years, conversations around representation and technology have forced some level of change. Camera companies have begun to acknowledge the gap and adjust how imaging systems handle diverse skin tones. Expanded calibration charts, improved dynamic range, and better testing practices have started to emerge.

Google’s Real Tone technology, introduced on Pixel phones from 2021, used broader datasets to tune Ai for accurate, natural representations across all complexions. Other brands like TECNO followed suit with theirUniversal Tone.

This progress did not happen naturally. It came from critique, public pressure, and Black photographers insisting that their work and their subjects deserved better tools. While improvement is visible, equity in photography is still being rebuilt, not fully achieved.

Visibility as Power

Photography is not just about images; it is about who gets seen clearly and who does not. Visibility shapes confidence, memory, and history. When Black skin is accurately represented, it challenges decades of neglect embedded in technology.

The issue was never your skin. It was the system behind the lens. Reclaiming visibility is not about aesthetics alone, it is about demanding fairness in how the world is documented.

Being seen is not a luxury. It is power.

You may also like...

Osimhen Unleashes Fury & Victory: The Galatasaray-Juventus Saga Unpacked!

Victor Osimhen's decisive goal led Galatasaray to a dramatic 7-5 aggregate victory over Juventus, securing their spot in...

Netflix Sensation 'Bridgerton' Season 4 Part 2 Sparks Debate with Bold Moves and Familiar Flaws

Bridgerton Season 4 Part 2 delves deeper into the forbidden romance of Benedict and Sophie, alongside a myriad of family...

Berlin Film Festival Rocked: Staff Rally Behind Chief Tricia Tuttle Amid Future Uncertainty

Berlin Film Festival director Tricia Tuttle faces an uncertain future as its governing body failed to decide on her cont...

Director Jafar Panahi Unveils The Secret Behind His Oscar-Nominated Film's Haunting End

Jafar Panahi's latest clandestine film, "It Was Just an Accident," explores the moral dilemmas of former political priso...

The 'Scrubs' Crew Spills Why Revival Needed a 'Resetting'

The beloved medical comedy <i>Scrubs</i> returns with a 30-minute revival, reuniting Zach Braff and Donald Faison as J.D...

Art World Cheers: Ken Nwadiogbu Crowned 2026 Young Generation Art Award Winner in Berlin

Nigerian-born, London-based artist Ken Nwadiogbu has been honored with the 2026 Young Generation Art Award, triumphing o...

Damson Idris Revs Up! British-Nigerian Actor Becomes Formula 1 Global Ambassador

British-Nigerian actor Damson Idris has been named Formula 1’s Global Brand Ambassador, a role that recognizes his deep ...

Cross-Border Rail Roars Back: TAZARA Link Between Tanzania and Zambia Resumes After Eight-Month Halt

TAZARA has resumed its cross-border passenger train services between Tanzania and Zambia after an eight-month suspension...