Urgent Call to Reform and Strengthen Music Education Across Africa

African music—long regarded as one of the continent’s most enduring repositories of history, identity, and collective memory—is now at the center of a growing call for urgent reform in music education. As global appetite for African sounds continues to expand, scholars warn that weak local educational structures threaten the survival and transmission of this cultural heritage across generations. The moment, they argue, demands deliberate and sustained investment in indigenous music education systems.

Across Africa, music has always been more than entertainment. It functions as a vessel for memory, moral instruction, political commentary, and communal identity. Yet despite its cultural weight, formal music education on the continent faces persistent challenges of marginalization, insufficient structure, and declining recognition. The current debate has moved beyond acknowledging these shortcomings to examining how music education can be rebuilt through intentional policy, curriculum reform, and institutional commitment.

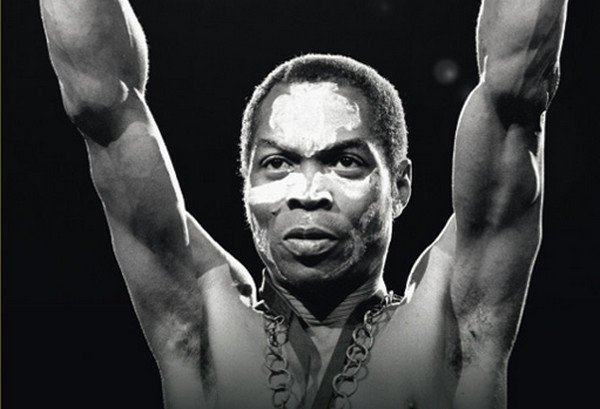

Professor Adeoluwa Okunade, a respected scholar in Ethnomusicology and African Musicology, describes the state of music education as one filled with promise but increasingly under threat. He explains that while colonial-era systems introduced structured Western music education, the post-independence period has seen a gradual erosion of formal music learning. In Nigeria, for example, recent curriculum revisions folded music into broader cultural and creative arts subjects—an approach Okunade believes has effectively submerged the discipline and weakened its academic identity.

According to him, the consequences extend far beyond the classroom. Music, he says, preserves Africa’s political struggles, economic realities, and social values, acting as a living archive of communal experience. Without proper structures to sustain it, those histories risk being lost. He warns that the early termination of formal music education—often ending at junior secondary school—squanders the immense creative potential visible in African children from a young age.

Professional bodies such as the Association of Nigerian Musicologists and the Society of Music Educators in Nigeria have intensified advocacy efforts in response. Delegations have engaged the Federal Ministry of Education, pressing for music to be restored as a standalone subject, drawing parallels to the successful reinstatement of history following public pressure. Okunade argues that meaningful music education must involve structured training that transforms raw talent into expertise, not merely informal exposure. Without this foundation, he says, Africa risks losing one of its most powerful cultural languages.

While policy engagement continues, scholars and practitioners are also turning to community spaces—churches, cultural centers, and local ensembles—to sustain musical practice. Religion, in particular, remains a crucial avenue for musical transmission. Through teaching and performance, African music has also found strong global resonance, with Okunade’s work reaching audiences in the United States, Brazil, and parts of Asia. He observes a growing international hunger for African musical expression, as listeners seek alternatives to dominant Western sounds.

This shift is reflected in evolving global perceptions of African music. Concepts such as African pianism—where Western instruments are played using African rhythmic and aesthetic principles—illustrate how indigenous musical values are reshaping global practice. Elements often dismissed in Western harmony, such as parallel movement, are central to African musical logic. Research into African music in the diaspora has further expanded global conversations about identity, with festivals, academic forums, and religious traditions in places like Brazil and Cuba demonstrating how African music survived displacement and evolved into enduring cultural symbols.

Religion has also played a protective role abroad, with African-derived spiritual music in the Americas functioning as a living historical archive. At home, Nigerian universities have made progress by incorporating indigenous instruments, ensembles, and performance traditions into their programs. Still, Okunade stresses that practical training remains inadequate, limiting students’ ability to fully internalize African musical techniques. He believes the renewed global interest offers a rare opportunity for African institutions to deepen investment in indigenous music education and assert a stronger cultural presence internationally.

Dr. Samuel Ajose, former Public Relations Officer of the Association of Nigerian Musicologists, shares cautious optimism about the direction of music education on the continent. He notes a gradual shift away from Western dominance toward recognition of indigenous knowledge systems. Music, he argues, plays a critical role in social development—supporting public health awareness, civic responsibility, national unity, and respect for labor. He also highlights its economic significance, pointing to African popular music as one of the continent’s most successful cultural exports.

However, Ajose warns that preservation efforts must accelerate in the age of artificial intelligence and digital aggregation. He advocates for systematic digitization, noting that African sounds remain underrepresented on global platforms. Without proactive documentation, future technologies may fail to reflect Africa’s cultural identity accurately. He describes this gap as existential, stressing that digital absence could translate into cultural erasure.

Efforts to strengthen scholarship and practice continue through professional recognition. The Association of Nigerian Musicologists annually confers its highest honor—the Fellow of the Association of Nigerian Musicologists—on individuals who have made exceptional contributions to research, teaching, performance, and community service. Among recent recipients is Professor Okunade, recognized for decades of scholarship, leadership in Pan-African music education, and pioneering research such as the Yoruba Art Music project. The honor, awarded through a rigorous selection process, is reserved for a select group whose work has significantly shaped the evolution of music education in Nigeria and beyond.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...