The Placebo Effect: Why Some Fake Surgeries Actually Work

The placebo effect is when a person experiences real improvements in their symptoms or condition after receiving a treatment that has no active medical ingredients or therapeutic effect, simply because they believe it will help.

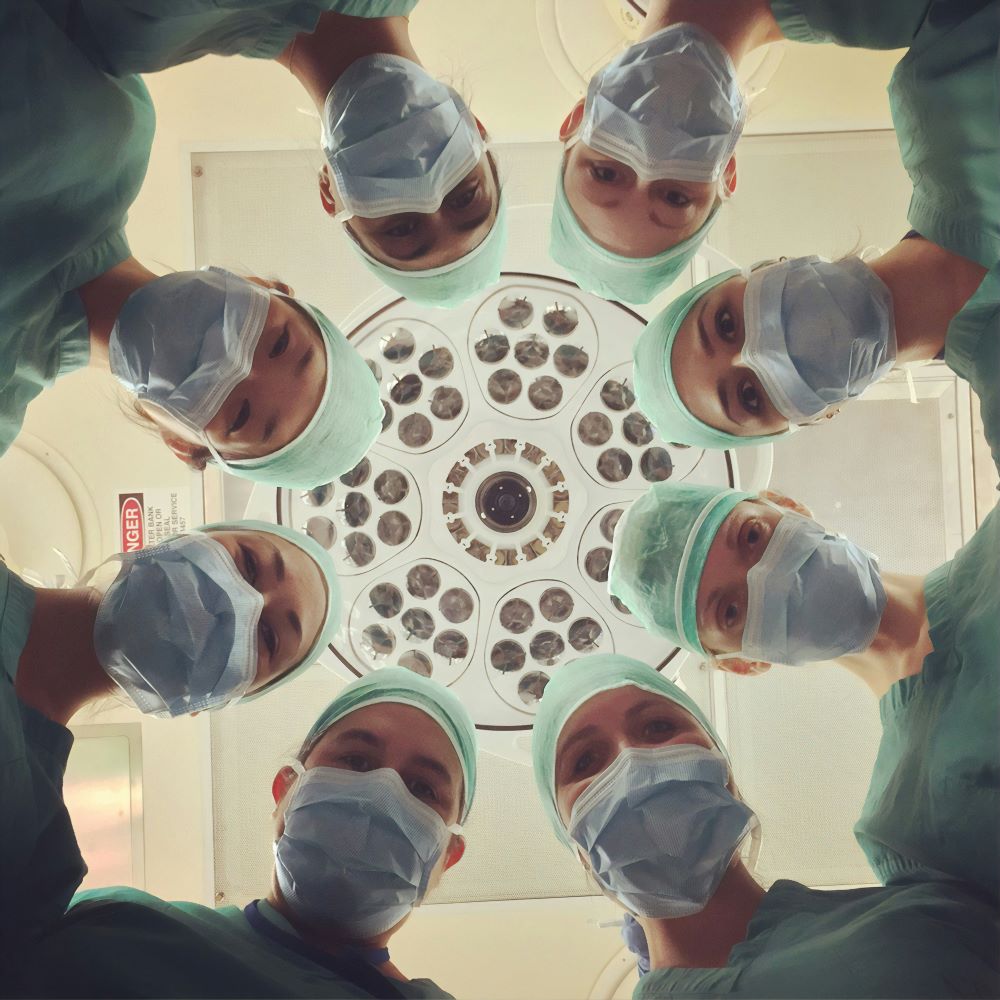

At the center of every hospital, behind the sharp tools and serious faces of surgical teams, is a quiet belief: that surgery helps people heal.

That when a body is cut and tools are used, pain and illness will go away. But over the past 20 years, this strong belief has been quietly challenged—not by opinions or stories, but by hard data. More and more studies show that some surgeries don’t work because of what they do, but simply because the surgery happens at all.

This is the strange and fascinating world of placebo surgeries—fake operations where patients go through everything, including cuts, anesthesia, and recovery, but the key part of the treatment is left out. And surprisingly, in many of these cases, patients still feel better.

The Uncomfortable Truth in the Numbers

In a large review of 53 placebo-controlled surgical trials, researchers found something surprising: 74% of patients who received fake (placebo) surgeries reported feeling better. That means nearly 3 out of 4 people improved, even though the surgery wasn’t real.

This iconic study took place in 2002. Researchers decided to test the effectiveness of arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis, a procedure routinely performed on aging, aching joints. Patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: one received a standard debridement procedure, another got a lavage (a flushing out of the joint), and the third underwent a sham surgery—incisions were made, instruments clattered, but nothing was actually done inside the knee.

The results were earth-shattering: there was no difference in outcomes between the real and the placebo surgeries. Patients in all three groups reported similar levels of pain relief and functional improvement. The scalpel had not healed them. The idea of the scalpel had.

In fact, in over half of the trials, there was no significant difference between fake and real surgeries. Real surgery was clearly better in only 49% of cases—and even then, the improvements were usually small.

A 2022 review of 100 surgical studies found that much of the improvement patients felt after minimally invasive surgeries—like knee or spinal procedures—wasn’t due to the surgery itself.

This isn’t a case of bad science or fake treatments. These were well-designed, peer-reviewed studies. But together, they paint a troubling picture: for some common procedures like arthroscopic knee surgery, the perceived benefits may be more about belief and expectation than what the surgery actually does.

More Surgeries, Same Illusion

Similar results were found in 2018 studies on vertebroplasty, a treatment for spinal fractures, especially in older adults. Even when doctors didn’t actually fix the broken bones and only pretended to do the procedure, many patients still felt just as much pain relief as those who got the real surgery.

The same pattern showed up with other minimally invasive procedures, like those used to treat chronic pain. In a review from 2016, 8 out of 10 studies found no clear proof that the real surgeries worked better than the fake ones.

Why Does This Happen?

How can this be?

The answer lies not in blood or bone, but in psychology and ritual. Surgery, after all, is not just a procedure—it’s a performance. The patient places their body into another’s hands. They are anesthetized, cut open, and stitched shut. They endure risk, pain, and recovery. This entire experience builds anticipation, faith, and most importantly, expectation.

When a patient believes they’ve been treated, the brain responds accordingly. Neurotransmitters shift, endorphins rise, and inflammatory markers fall. The body isn’t faking it—it is biologically reacting to belief. The placebo effect is not imagined relief; it is measurable, chemical, and real.

This is especially potent in conditions driven by subjective symptoms like pain, where perception and physiology blur. And it explains why, in so many studies, patients in the placebo group walked away feeling just as healed as those who underwent the real procedure.

The Scalpel’s Ethical Dilemma

But this knowledge comes with a sharp edge. Performing placebo surgeries is ethically fraught. Even though no therapeutic action is taken, the risks are real—incisions, anesthesia, and recovery time all carry potential harm. For a placebo trial to be justified, it must pass through rigorous ethical review, and participants must be fully informed and willing to take part in what is, essentially, an elaborate medical illusion.

Still, the real scandal may not be in the placebo surgeries themselves. It may lie in how many real surgeries are being performed without clear, data-backed benefit—surgeries that may be no more effective than their simulated counterparts, but carry significantly more cost, risk, and recovery burden.

Conclusion: The Knife’s Hidden Lesson

The story these numbers tell is not one of deception, but of deep human vulnerability—and power. We are hardwired to respond to care, to belief, to ritual. And sometimes, that response is as potent as the most precise surgical intervention. Data-driven research has revealed that placebo surgeries don’t just fool patients—they can truly heal, in ways science is only beginning to understand.

But these findings also demand humility from the medical world. If so many surgeries are only marginally better—or not better at all—than a placebo, then we must re-evaluate which procedures are truly necessary. Not just for the sake of cost or efficiency, but for the integrity of care itself.

Because sometimes, it’s not the hand that holds the scalpel that heals. It’s the mind that believes it’s being healed.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...