Seeing Beyond Sight—The Language of Touch and the Quiet Power of Braille

Growing up, I once read a story that never really left me. It was about a group of blind men who went out and encountered an elephant for the first time. Each man reached out and touched a different part of its body to feel what the elephant truly was. One held the trunk and said the elephant was like a snake. Another touched the leg and insisted it was like a pillar. One felt the ear and swore it was a wide fan. None of them were entirely wrong, yet none of them saw the full picture. But that was never the point of the story for me.

What stayed with me was not their disagreement, but their determination. Despite being visually impaired, these men still wanted to understand the world for themselves. They did not sit back and wait for descriptions to be handed to them. They reached out—literally—to know, to interpret, to experience. They refused to be passive observers of life simply because sight was denied to them.

That story comes back to me every time conversations around blindness are reduced to pity or helplessness and on days like January 4th—World Braille Day—even though it has passed, it is a day that exists not just to acknowledge a system of reading and writing, but to remind us that vision does not end where sight fails.

This article is not about loss or speaking of impairments, it is one about adaptation. It is about how human curiosity refuses to die, even when one of its primary tools is taken away and it is about Braille, not as a symbol of disability, but as evidence that life continues, learns, and insists on inclusion.

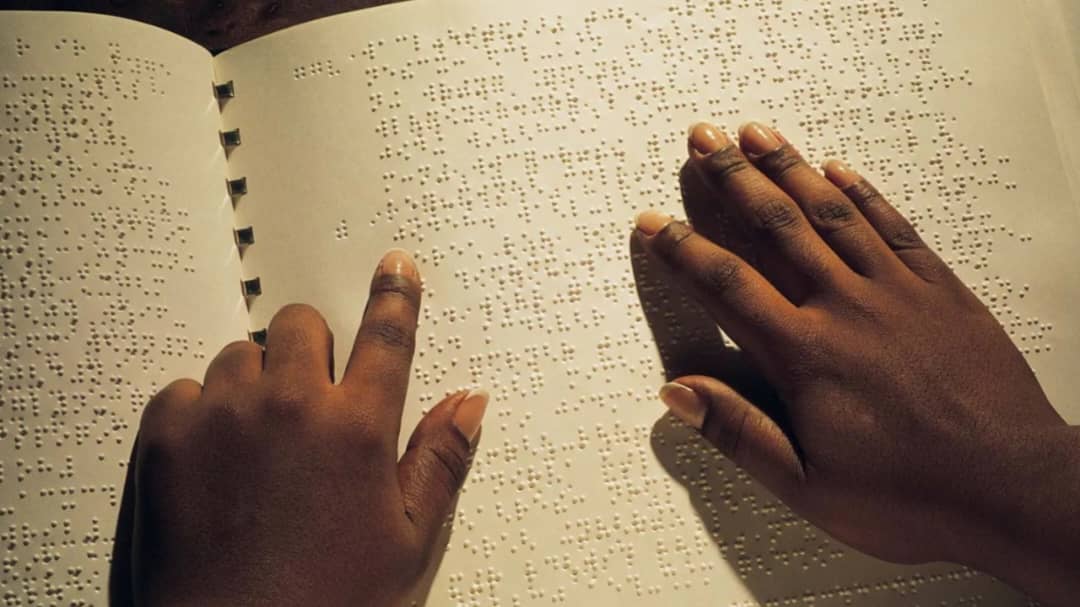

Braille: When Touch Became a Language

The Braille is often misunderstood as a consolation prize for failed vision. In reality, it is one of the most radical tools of independence ever created. It was invented in the early 19th century by Louis Braille, a French educator who lost his sight at the age of three due to an accident. Like many blind children of his time, he was expected to adapt quietly to a world that was not built for him. Instead, he chose to change the rules.

At just 15 years old, Louis Braille developed a tactile writing system based on raised dots that could be read through touch. His system allowed blind individuals not only to read but also to write—something that had been nearly impossible before his time. This was revolutionary and mind blowing at the time the Braille was invented, because for the first time, visually impaired people could access education, knowledge, and self-expression without intermediaries.

Over the years, the Braille has evolved, it has expanded beyond literature into mathematics, science, music, and digital technology. Today, Braille exists on paper, on screens, on elevators, on currency, and in public spaces. It has adapted to languages across the world, including African languages, proving that accessibility is not static—it grows with society.

What the Braille actually represents is larger than dots carefully crafted on a page, it represents dignity. It tells the world that blindness does not erase intelligence, ambition, or contribution. It is a reminder that accessibility is not charity, it is infrastructure that fuels the world economy and overall growth.

Vision Is Fragile, and Sight Does Not Disappear Overnight

One of the most dangerous misconceptions about visual impairment is the belief that it happens suddenly, accidentally, dramatically, and without warning. In reality, vision loss often begins quietly, a slight eye pain dismissed as stress, blurred vision blamed on tiredness, persistent itching ignored. These small discomforts are often normalized until they become irreversible.

Vision does not vanish overnight—it changes, it fluctuates, it declines and in many cases, it could have been managed or slowed with early medical care. This is where responsibility comes in—especially for parents and guardians.

When children complain about changes in their eyesight, it should never be brushed aside and maybe attributing it to carelessness or playful behaviours. Growing teens, students, and even adults deserve to be taken seriously when they say something feels off.

Routine eye checkups are not optional luxuries. They are preventive care measures, yet in many African societies, eye health is often neglected until the damage is done and cannot be reversed.

Many times we wait for emergencies before acting, we adapt to discomfort instead of investigating it and by the time intervention happens, the narrative shifts from prevention to coping.

World Braille Day should not only remind us of those who are already visually impaired—it should remind us to care for those whose visions are quietly declining. The honest truth is that care is not panic—it is attentiveness, it is listening early, it is choosing not to let life “just happen” to us without medical awareness.

Beyond Pity: Inclusion, Systems, and Seeing People Fully

The greatest injustice faced by visually impaired individuals is not blindness—it is pity disguised as concern. Love does not look like treating someone as fragile or helpless. Empathy does not mean reducing a person to their impairment. Visually impaired individuals are not objects of unending sympathy; they are people with full emotional, intellectual, and professional capacity.

Braille is not a symbol of failure, it is proof that life adapts no matter the circumstance. That knowledge finds new pathways and inclusion is possible when society chooses to care.

Being visually impaired does not impair potential in any way. It does not disqualify dreams of any individual, their dreams still remain valid. It does not relegate anyone to the background of life, they still have a fair chance too.

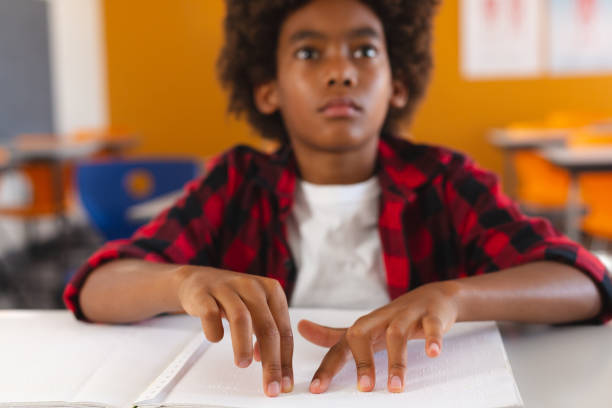

African societies, in particular, must move beyond performative concern to genuine and progressive structural inclusion. Schools must be equipped with learning tools for visually impaired children to include them into the curriculum of education.

Public spaces must be designed with accessibility for everyone in mind. Employment systems must focus on ability, not limitation. Inclusion should not depend on individual kindness—it should be embedded into systems.

World Braille Day exists to remind us that everyone deserves to be seen, even when they cannot see. And all of this would happen not through pity, but through policy and not through sympathy, but through structure. Because the measure of a society is not how it treats its most visible members, but how it supports those navigating life differently.

In summary, vision is not just about the eyes. It is about how far a society is willing to see beyond assumptions and the Braille, in its quiet simplicity, continues to teach the world that sight is only one way of knowing and never the only way of living.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...