Zimbabwe And The Loaf of Bread That Cost a Trillion

In 1980, Zimbabwe emerged from colonial rule with pride, promise, and a new currency: the Zimbabwean dollar. Pegged at par with the US dollar, the currency was strong, trusted, and widely accepted. For a while, it seemed like the beginning of an African economic success story.

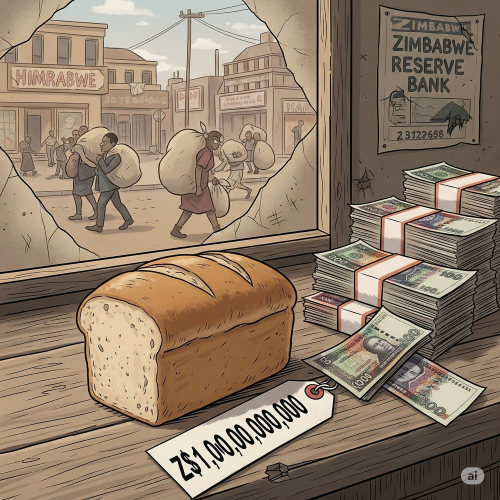

The streets of Harare were busy with commerce, fueled by a robust agricultural sector and a well-educated population. In those early years, a loaf of bread cost about one Zimbabwean dollar. Life was predictable. The currency held value. The baker knew what to charge, and the customer knew what to expect.

But as the decades rolled on, that single loaf would chart the rise and spectacular collapse of one of the most volatile currencies in modern history. By mid-2008, that same loaf cost 100 billion Zimbabwe dollars. Within months, it would soar into the trillions. By the end, the money itself had become more valuable as novelty paper than legal tender.

A Nation's Descent into Hyperinflation

Image Credit: Radar Africa

The fall began slowly, masked by years of overconfidence. Through the 1990s, Zimbabwe’s economy started showing signs of distress. In 1997, the government made an unbudgeted payout to war veterans—about Z$50,000 each—triggering a seismic loss of market confidence. The Zimbabwean dollar lost 71 percent of its value in a single day. It was dubbed “Black Friday,” but the panic was just beginning.

From that point forward, the government leaned more heavily on the printing press. Budget deficits ballooned. By the early 2000s, the situation worsened. President Robert Mugabe’s land reform program, intended to redistribute land from white commercial farmers to black Zimbabweans was executed chaotically. Once-thriving farms were abandoned or mismanaged. Agricultural output, the backbone of Zimbabwe’s economy, collapsed. Exports plummeted. Food shortages followed.

To fund the growing deficit, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe printed more money. And then more. By 2003, the cost of a loaf of bread had jumped to Z$500. By early 2007, it cost Z$16,000. Inflation was no longer creeping; it was sprinting.

By 2008, Zimbabwe had entered the most extreme hyperinflation ever recorded in peacetime. The annual inflation rate reached an unfathomable 516 quintillion percent—that’s 516 followed by eighteen zeros. Prices doubled roughly every 24 hours. Currency notes were printed in trillions, then quadrillions. That same loaf of bread that had once cost Z$1 was now priced at Z$100 billion in July 2008—and just five months later, it was selling for Z$7 trillion.

Money became meaningless. Shops stopped using price tags because they couldn’t update them fast enough. Salaries were paid in wheelbarrows of cash, and employees had to run to stores during lunch breaks to spend their wages before prices jumped again. Many people stopped using Zimbabwean dollars altogether, bartering instead with fuel, maize, or foreign currency.

The 100 Trillion-Dollar Bill

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

In early 2009, Zimbabwe issued its most infamous banknote: the Z$100 trillion note. It was both absurd and tragic—legal tender whose face value couldn’t buy a loaf of bread. In the global financial imagination, that note became the symbol of hyperinflation’s absurdity. Tourists bought them as souvenirs. Zimbabweans treated them with weary disdain.

Three separate redenominations had already failed. In 2006, the government knocked off three zeroes. In 2008, it removed ten. In 2009, it tried again—this time slicing off twelve. None of it worked. The economy was fundamentally broken, not just the arithmetic.

Eventually, the government gave in. In February 2009, Zimbabwe abandoned its currency entirely, legalizing the use of foreign currencies such as the US dollar, South African rand, and the euro.

Overnight, the Zimbabwean dollar was effectively dead. In 2015, it was formally demonetized, with a conversion rate so extreme it was almost comedic: 35 quadrillion Zimbabwean dollars for one US dollar.

Dollarization brought relief. Inflation evaporated. Bread became affordable again—at around $1 USD per loaf. The economy stabilized. Businesses reopened. But scars ran deep. Life savings had vanished. Pensioners who had worked their entire lives were left destitute. Confidence in national institutions was shattered.

A Second Chance That Wasn’t

A decade later, in 2019, Zimbabwe reintroduced its national currency, this time called the Zimbabwean dollar again—though locals often referred to it as the RTGS or ZWL. It was meant to mark a return to monetary sovereignty.

But history repeated itself with uncanny speed. Inflation crept back, then sprinted. By the end of 2019, prices were again rising at an annual rate of over 500 percent. The government insisted this was temporary. Zimbabweans, more experienced than hopeful, knew better.

In 2020, inflation surged to 837.5 percent. The money supply ballooned. By early 2024, the ZWL had lost more than 70 percent of its value. The exchange rate reached Z$30,000 per US dollar. Bread, once again, was out of reach for many if priced in local currency. For the average Zimbabwean, the reintroduction of the dollar had felt like a cruel joke—a sequel to a nightmare they thought they had survived.

A New Currency, Backed by Gold—And Skepticism

In April 2024, Zimbabwe launched yet another bold new experiment: a gold-backed currency known as the ZiG, short for Zimbabwe Gold. The government claimed it would restore faith in money by tying it to real reserves. Initially, the exchange rate was set at 13.56 ZiG to the US dollar.

But optimism was short-lived. Within months, the ZiG had lost nearly half its value on the black market. Officially, it traded at around 24 per US dollar. Unofficially, some were selling it at 50 per dollar or worse.

For Zimbabweans, the psychological trauma lingers. And that loaf of bread—still priced in US dollars for stability, has become more than food. It’s become a measure of trust, or rather the absence of it. When the price of bread remains steady, Zimbabweans breathe easier. When it shifts, they prepare for another storm.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

The Loaf as Ledger

Tracking the price of bread in Zimbabwe is not just an anecdote. It’s an economic instrument. In normal economies, the cost of bread is boring. In Zimbabwe, it has been prophetic. It has mirrored the strength of institutions, the honesty of leadership, the reliability of data, and the consequences of fiscal fantasy.

From Z$1 in 1990 to Z$100 billion in mid-2008 to Z$7 trillion just months later, the bread told the truth when governments did not.

Money is, ultimately, a promise—a shared belief in value. In Zimbabwe, that promise was broken so many times that even gold, even new notes, even rebranding couldn’t easily rebuild it.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...