Who Told You Afro Hair Isn’t Formal?

I once overheard a girl whisper to her friend during a convocation ceremony, “She should have at least made her hair.”

The girl in question had a glorious afro, black, lush, round. The kind of hair that doesn’t need to explain itself. The kind that takes up space, as it should. But at that moment, all anyone could see was that she didn’t “do” it. Because in their minds, Afro equates to unfinished. Afro equates to informal.

This is not new. If anything, it is very predictable.

We have grown up around these silent corrections. “Your hair is rough.” “Go and pack it well.” “Are you going to the office like that?”

At first, you think they are just being helpful. Until you realise what they are actually saying: your hair, in its natural form, is not good enough for this space.

And by “this space,” they mean anything remotely professional, respectable, or sacred.

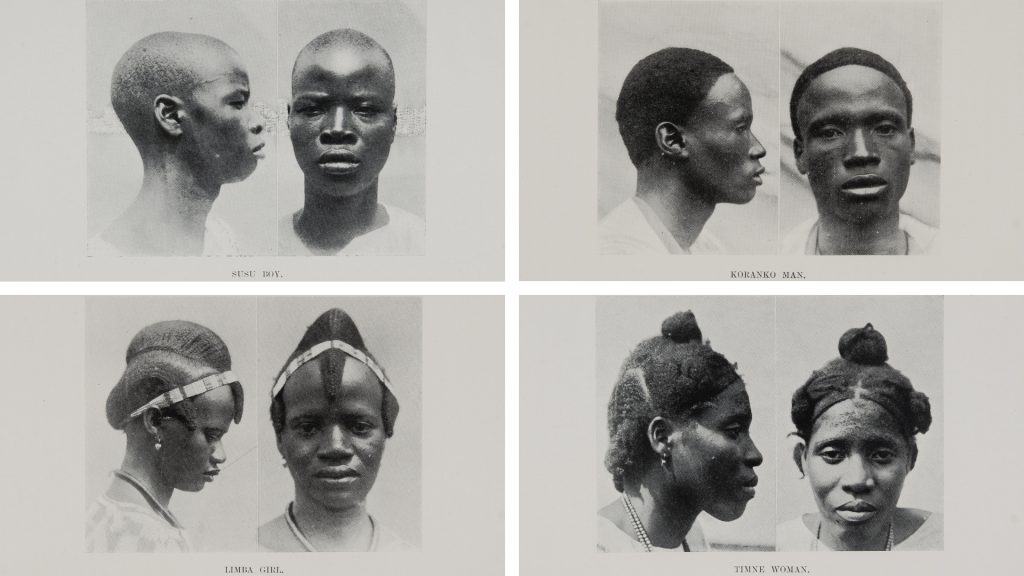

Photo Credit: Entanglements

The Colonial Gaze Behind the Comb

Let us call it what it is; this is conditioning. The kind inherited from generations who were told their features had to be corrected before they could be accepted.

Our hair was one of the first things the colonial gaze attacked. It did not conform to European standards of beauty, so it had to be “tamed.”

In Western societies, neatness was defined by sleekness, traits tightly coiled African hair did not naturally possess. So, over time, straight hair became the gold standard. It was professional, proper and presentable. It was safe.

In most African schools, there are policies that banned certain hairstyles for being “unkept” or “distracting.” What they meant was that this hair makes us uncomfortable. It reminds us too much of Africa, too much of freedom, too much of defiance.

We internalised that discomfort and passed it down through generations. Not always in violent ways, but in small, painful ones. The “be neat” mantra. The hot comb days. The relaxer burns we wore like rites of passage.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

“Are You Not Going to Do Your Hair?”

These are the microaggressions we rarely name out loud. Because sometimes it is not outright discrimination, it is just the lingering questions, the passive-aggressive suggestions.

It is the auntie who hugs you at a wedding and whispers, “You didn’t have time to make your hair?”

It is the HR manager who says, “This look is nice, but not exactly corporate.”

It is the school administrator who insists that natural hair must be braided or threaded, anything but loose and loud.

It is how we talk about "doing" our hair as if our hair in its natural state is somehow undone.

These statements seem harmless until you start realising how often they come up, how deeply they shape our self-image and career decisions. For a lot of Black women, navigating workspaces is not just about competence; it is about conformity. And hair is the first test.

If your hair looks too free, too full, too “nappy,” you will be seen as unserious. Or worse, uncultured.

Straight Hair Is Not Just a Style, It is a Survival Strategy

Let us not pretend, a lot of us straightened our hair not for style but for safety.

Relaxers were about fitting in. Wigs were about getting hired. Weaves were about being taken seriously. The decision to straighten or cover up was never always rooted in vanity. Sometimes it was just about reducing the risk of being rejected.

We knew early on that “presentation” could protect us. And presentation was always defined by your proximity to whiteness. The straighter your hair, the more likely you were to be perceived as professional, clean, disciplined.

This is not to demonise straight hair or the women who choose it. There is nothing wrong with versatility. The problem is when choice becomes a code for survival, when afro-textured hair is only accepted when it is stretched, slicked back, or hidden altogether.

You start to ask: is this really about grooming? Or is this about control?

The Politics of Respectability and the “Good Hair” Complex

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Hair became a battleground in the war for respectability. We were taught to earn our way into rooms by sacrificing parts of ourselves. Don’t be too loud, don’t be too dark, don’t be too African.

And definitely, don’t let your hair be too natural. You hear it even now in subtle comments:

“She has good hair.” “She’s lucky her natural hair is soft.” “Natural is nice, but only if you can manage it.”

The texture hierarchy is still alive where looser curls get praised and tighter coils get pathologised. So even when people “accept” natural hair, they prefer it in diluted, disciplined forms.

We have simply moved from “hide your hair” to “make it look cute enough for us to tolerate.”

Photo Credit: The Modern Met

Wearing the Crown Proudly

The natural hair movement fueled by bloggers, YouTubers, and unapologetic public figures has shifted the conversation. We have watched Black women cut off years of processed hair and start again with pride. We have seen social media platforms fill up with afro puffs, loc buns, wash-and-goes, and twist-outs.

In Nigeria, local brands are emerging, selling products made for our textures by people who understand them. In the US, laws like the CROWN Act are pushing back against hair discrimination in schools and workplaces.

We now have CEOs with locs. News anchors with short afros. Actresses walking red carpets with hair that defies gravity.

Natural hair is not just a style anymore, it is a statement. A refusal to edit ourselves for acceptance. A declaration that we don’t have to trade our texture for our respect.

Let’s Not Pretend We Have Arrived

There is still a form of resistance. The kind that hides behind dress codes, school rules, and PR statements about “brand alignment.”

We are still hearing about students being punished for afros, cornrows, or dreadlocks. We are still seeing models being asked to “do something about that hair” on set. We are still watching women walk into interviews with straight-texture wigs because they know the risk of “coming as they are.”

So, no, we are not there yet. The revolution is visible, but it is not complete. Representation does not automatically mean respect. Visibility is not the same as validation.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Until natural hair is treated with the same normalcy and neutrality as straight hair, the battle continues.

If Your System Can’t Handle My Hair, It Is Your System That Is Unprofessional

Let us flip the question. Who told you afro hair isn’t formal?

Who decided that a style thousands of years older than the modern blazer is somehow inappropriate? Who said “neat” means “non-African”? Who taught us to shrink ourselves to fit someone else’s definition of elegance?

Because here is what is true: Afro hair is not unfinished.

It is not a rebellion. It is not a distraction.

It is history and identity. It is beautiful.

If your office, your school, your church, your system can’t handle that, then maybe it is your system that needs a makeover.

Maybe the real issue was never the hair.

Recommended Articles

There are no posts under this category.You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...