When Playing Games Took a Village: Indigenous Games vs Modern Games

There once was a time when the sound of laughter echoed across open fields, when sticks, stones, and pure imagination were enough to create entire worlds. Children didn’t need sophisticated devices to connect, they only needed each other. Games were shared, not downloaded. From the rhythmic slap of skipping ropes to the calculated pause before flicking a pebble in ayo, oware, or mancala, leisure in Africa once had a tune that was played by the community.

Play was never just play, it was instruction, competition, storytelling, and socializing rolled into one big ball. Through games, everyone had a sense of belonging. But that was before digital games and global culture redefined fun.

How then did the fun, lively village slowly disappear behind large screens, headphones and controllers?

Games as Culture, Not Just Pastime

In most African societies, games weren’t just mere hobbies, they were part of life’s design. Every community had its own form of play that mirrored its environment, values, and rhythm.

In Ghana and Nigeria, ayo (other varieties are called oware or mancala) was a mathematical game, which taught risk management, problem solving and resilience. In Kenya, ajua did the same, teaching logic, strategy and patience. Southern Africa had morabaraba , a tactical board game that mirrored the intelligence of cattle herders, teaching forward planning and observation. For many, these weren’t leisure in the Western sense, they were education disguised as fun. The playground was basically an outdoor classroom, and older players became mentors. Children learned by watching, imitating, and participating. The highlight of it was that everyone played. Playtime blurred gender, age, and class lines. Elders joined in when the game allowed, not because they missed childhood, but because play itself was an expression of community.

When Fun Had a Tribe

Games carried the unspoken principle that joy, like food, was best enjoyed together. You could find hide-and-seek equivalents in nearly every African society, each with its own name and rhythm. Across these games, laughter became a universal language. Teasing had purpose, it sharpened one's wit and taught endurance. Even losing wasn’t seen as humiliation, it was social training.

Play and culture used to be intertwined, a means to show a sense of belonging. This collective energy extended beyond childhood, as even Men and women used it as a means to relax after work or to connect during work hours. This, simply put, was life expressing itself in community. We say “it takes a village to raise a child”, but it also takes a village to entertain one. And so, leisure was communal because living was communal.

The Arrival of Screens

Over time, everything changed. Urbanization brought about smaller compounds and busier streets. Children began to stay indoors due to safety concerns. The Western-style education left little time for unstructured play, and with technology came a quieter but deeper shift. A shift from physical community to digital solitude.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Modern games helped to reshape what fun looked like. They offered worlds of their own, yet, they also turned play into something personal and private. The same African child who once ran barefoot through dust now battles opponents halfway across the world through a glowing screen.

There’s no doubt that digital games have their merits, they teach reflex, problem-solving, and creativity in an advanced manner. They connect global players in ways that would have been otherwise impossible. But, something vital was lost in the process, which is presence. The warmth of shared laughter, the lessons learned and the fairness those games came with were replaced.

The New Rules of Play

It would be unfair to reminisce about the past without acknowledging the appeal of modern gaming. It’s very thrilling, immersive, and increasingly inclusive. The rise of African developers is also reclaiming space, with titles like Aurion: Legacy of the Kori-Odan giving global gaming an African feel.

But, there’s still an undeniable shift in how we experience joy. Where indigenous games were collective, modern games are curated. You choose your console, your difficulty level, your opponents. Hence, fun has become individualized, filtered through preference and privacy. Indigenous games, on the other hand, thrived on compromise and participation. You didn’t always get your way, you played whatever the group decided. The rules weren’t programmed, they were negotiated. And in those negotiations, children learned democracy before they knew the word for it.

Today, children are far more entertained but less connected. They win games alone, lose alone, and restart alone. The village has been replaced by usernames and avatars, the shared shouts of victory replaced by the faint clicks of a console.

Cultural Memory in Play

Games carry culture and when we lose them, we lose more than just fun. We lose ways of thinking, teaching, and bonding. Indigenous games were oral archives, passed down by repetition and participation. They exist now more as symbols of our heritage than everyday living habits. In urban communities, space for traditional play has vanished.

But, there are some sparks of revival. Some African educators now use indigenous games to teach math, logic, and teamwork. Community centres in Kenya, South Africa, and Ghana host cultural play festivals. Social media isn't left out as well, as creators remix childhood games into challenges, keeping them alive in new forms. It shows that while the village might have changed, the instinct to connect through play remains.

Perhaps that’s the secret, we don’t have to choose between old and new. The challenge isn’t preserving dust-and-stick play forever, it’s remembering why we played in the first place.

Why Games Still Need a Village

When games took a village, fun was everyone’s business. You couldn’t sulk for too long because someone would drag you back into the circle. You learned to share space, time, and laughter, not because it was convenient, but because the community demanded it.

Social Insight

Navigate the Rhythms of African Communities

Bold Conversations. Real Impact. True Narratives.

Modern life, as convenient as it is, often steals that sense of shared joy. Rarely do we gather in the same way that our ancestors did. The village is gone, yet the longing for it lingers.

The lesson in this is simple: progress doesn’t have to mean isolation. We can bring the village back even in the age of screens, not by turning off technology, but by turning toward each other again. Because when games took a village, we didn’t just learn how to win. We learned how to belong.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

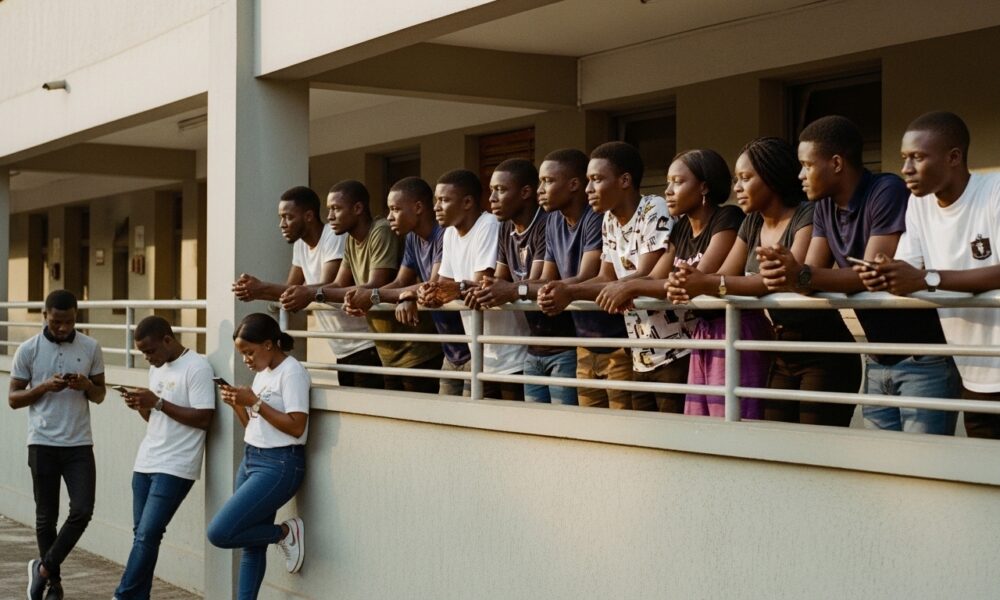

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...