The Village That Owns No Land: How Communal Ownership Shapes Life in Rural Africa

INTRODUCTION: A Village Without Private Land

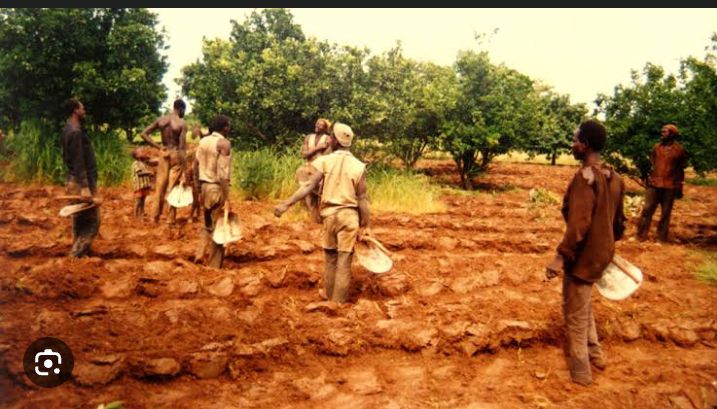

At sunrise, the dusty footpaths of many African villages are always alive. Children race barefoot to fetch water from the communal well, their laughter echoing across the valley. Farmers tend to the earth with patient hands, planting seeds in fields they have worked for generations, yet not a single plot is legally theirs. Goats wander freely, unbothered by boundaries, because here, boundaries are more social than physical.

In this villages, no one holds a land deed. No family can claim a fence line or title document. Yet, remarkably, no one is landless, and homelessness is unheard of. Every villager has a place to farm, to build, to belong. This isn’t a utopian experiment or a socialist reform, it is a centuries-old system rooted in African tradition, where the land is seen as a shared inheritance from ancestors, to be guarded for future generations rather than traded as a commodity.

Photo Credit : Google Image

But in a rapidly globalizing world, where economies thrive on property markets and private investment, can such a community model still survive? Can a village that rejects private land ownership compete in a modern economy driven by titles, collateral, and legal ownership? These questions lie at the heart of a debate that is as much about identity and tradition as it is about development and survival.

The Roots of Communal Land Ownership

In many African societies, the idea of owning land in the Western sense simply did not exist for centuries. Instead, land was seen as a living legacy, a sacred trust passed down from ancestors to be preserved for future generations. It wasn’t a personal asset to be bought, sold, or fenced off; it was a shared resource that bound the community together.

Communal land systems often emerged from tribal and clan-based arrangements, where chiefs, elders, or councils acted as custodians rather than landlords. In this worldview, land was not property, but heritage, something you belonged to, rather than something that belonged to you.

Across Africa, variations of this system still exist: among the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania, grazing pastures are held collectively, allowing herders to move freely with their cattle according to seasonal needs. In many Igbo communities of Nigeria, ancestral compounds remain family-owned for generations, with no single individual holding exclusive rights. Similarly, in Zulu traditional systems, large tracts of land are reserved for communal grazing, ensuring that even the poorest households have access to pasture.

This philosophy was more than cultural tradition, it was a survival strategy in environments where cooperation often meant the difference between prosperity and famine. In such systems, the wellbeing of the community outweighed the wealth of the individual.

How It Works: The Social Contract of Shared Land

In a village without private land ownership, the rhythm of life depends on an unwritten yet deeply respected social contract. Land is held collectively, but access is granted based on need, contribution, and lineage.

Allocation is often overseen by a council of elders, the chief, or a community assembly. When a family needs farmland, they approach the elders, who assign a portion of the communal land for use, not for sale. This allocation is temporary in a legal sense, yet it can last generations as long as the family remains part of the community and respects its rules.

Photo Credit: Google Image

Disputes rarely end up in a courtroom. Instead, they are resolved in public gatherings where both sides present their case, and the elders, acting as both judges and mediators, give a ruling. The aim is not punishment but restoration, ensuring peace and fairness so that harmony is preserved.

Inheritance follows a similar communal logic. A farmer cannot pass land down in the Western sense, but their children inherit the right to use the same portion of land, provided they continue to live in and contribute to the village. If heirs leave for the city or abandon their responsibilities, the land reverts to the communal pool, ready to serve another family in need.

The Benefits: Security, Solidarity, and Sustainability

In a world where land disputes often spark bitter feuds and displacement, a village without private land titles might sound like a fragile experiment. Yet, in many parts of rural Africa, it has proven remarkably resilient, precisely because ownership is collective.

Communal land ownership creates security that money can’t buy. Every family knows they will have a place to farm and build a home, regardless of economic status. Even the poorest households have access to fertile soil, ensuring that food and shelter are not privileges but rights.

This shared ownership also breeds solidarity. When one farmer’s crops fail, neighbors step in to help, knowing that tomorrow they might need the same kindness. Celebrations, harvests, and even house-building projects become communal affairs, deepening trust and social cohesion.

From an environmental perspective, shared land fosters sustainability. Because the land belongs to everyone and no one, the community enforces responsible farming, rotational grazing, and tree preservation. The goal is to leave the land as fertile for the next generation as it was for the last.

Lastly, social equality is baked into the system. Without the possibility of amassing large private estates, there is less risk of land monopolies, eviction, or forced migration.

THE CHALLENGES: Tradition Meets Modern Economics

While communal land ownership offers stability and solidarity, it also faces mounting pressures from the realities of a modern economy. One of the most immediate obstacles is access to capital. In most financial systems, land titles serve as collateral for bank loans. Without individual deeds, farmers and entrepreneurs are often locked out of formal credit, limiting their ability to expand businesses, invest in new equipment, or weather economic shocks.

Photo Credit: Google Image

The generational gap is another fault line. Younger community members, especially those who migrate to cities, often see the system as restrictive. Influenced by urban values and individual wealth-building aspirations, they question why land cannot be bought, sold, or leveraged for personal gain. Some return to the village pushing for private plots, sparking debates that test the community’s unity.

Governments, too, are applying pressure. In the name of development and taxation, many push to formalize land ownership through registration and titling. Officials argue it streamlines infrastructure projects, attracts investors, and increases public revenue. But for communities with deep cultural ties to shared land, such policies feel like an erosion of identity and in some cases, a prelude to displacement.

These tensions reveal the central dilemma: how to preserve a centuries-old tradition while adapting to the economic demands of the 21st century. The survival of such systems may depend on finding creative middle grounds that honor heritage without stifling progress.

The Future of Communal Land in Africa

The fate of Africa’s communal land systems hangs in a delicate balance between cultural preservation and economic modernization. At its heart is a question: can a tradition built on collective stewardship survive in a world that increasingly rewards individual ownership?

For many elders and traditional leaders, communal land is more than soil, it is the lifeblood of the community, a sacred inheritance that binds generations together. They argue that once land becomes a commodity, the community’s soul risks being sold alongside it. In their view, modernization should come in ways that strengthen tradition, not dismantle it.

On the other side, younger generations, particularly those shaped by urban life, see the current system as limiting. They point out that without land titles, they cannot access loans, invest in larger ventures, or fully participate in a global economy that prizes capital mobility. For them, the question is not whether tradition should evolve, but how fast.

The debate is not only generational but also geographical. Rural communities, where livelihoods are tied directly to the land, tend to favor the status quo, while urban migrants push for reforms that allow land to generate greater economic returns.

Hybrid models are emerging as possible middle grounds. Community-owned cooperatives could preserve collective ownership while granting partial private leasing rights, enabling individuals to invest and profit without undermining communal control. Some regions are experimenting with long-term lease agreements, shared profit arrangements, and community trust funds to finance development while keeping land within the collective’s hands.

Whether these solutions take root will depend on dialogue, trust, and adaptive governance. If handled with sensitivity, Africa’s communal lands could evolve into models that protect heritage while embracing the economic realities of a changing continent, proving that tradition and progress need not be sworn enemies.

CONCLUSION: Ownership Beyond Paper

Communal land ownership challenges the modern obsession with property deeds and market value. It asks us to consider whether true security lies not in a piece of paper, but in the bonds between people, in trust, cooperation, and shared responsibility. While private ownership promises individual autonomy, it often comes with risks of isolation, exploitation, and displacement. Communal systems, despite their flaws, offer a form of stability rooted in identity and belonging.

As Africa navigates the crossroads of tradition and modernization, the question remains: In a world racing toward privatization, could the continent’s oldest land systems hold the key to a more equitable and sustainable future?

Recommended Articles

Crypto World Buzzes: Yellow Card Enlists Psycho YP as Brand Face

Yellow Card Financial, Africa's rapidly growing crypto exchange, has partnered with Nigerian artist Psycho YP as its new...

E-commerce Giant Jumia Reports Stellar 13% Revenue Surge to $188.9 Million, Driven by Nigerian Market

Africa's e-commerce leader, Jumia Technologies AG, reported a 13% revenue surge in 2025, driven by strong GMV and increa...

Jumia's Bold Exit: Algeria Operations Halted for Profitability Push

Jumia exited Algeria in February 2026, part of a strategy to streamline operations and focus on profitable markets amids...

Africa's Next Big Bet: Tapping into the $12 Billion Decentralized Prediction Market

The global Decentralised Prediction Market (DPM) sector has seen a massive surge, yet Africa, despite its high crypto ad...

Bitcoin Philanthropy: Paxful Co-founder Ray Youssef Funds 100 Nigerian Schools

Ray Youssef, co-founder of Paxful and Built With Bitcoin, discusses the transformative power of peer-to-peer Bitcoin ado...

Microsoft and Women in Tech SA Launch Massive AI Training Initiative Across Africa

The ElevateHer AI programme, a collaboration between Women in Tech South Africa, Absa Group, and Microsoft Elevate, is e...

You may also like...

If Gender Is a Social Construct, Who Built It And Why Are We Still Living Inside It?

If gender is a social construct, who built it—and why does it still shape our lives? This deep dive explores power, colo...

Be Honest: Are You Actually Funny or Just Loud? Find Your Humour Type

Are you actually funny or just loud? Discover your humour type—from sarcastic to accidental comedian—and learn how your ...

Ndidi's Besiktas Revelation: Why He Chose Turkey Over Man Utd Dreams

Super Eagles midfielder Wilfred Ndidi explained his decision to join Besiktas, citing the club's appealing project, stro...

Tom Hardy Returns! Venom Roars Back to the Big Screen in New Movie!

Two years after its last cinematic outing, Venom is set to return in an animated feature film from Sony Pictures Animati...

Marvel Shakes Up Spider-Verse with Nicolas Cage's Groundbreaking New Series!

Nicolas Cage is set to star as Ben Reilly in the upcoming live-action 'Spider-Noir' series on Prime Video, moving beyond...

Bad Bunny's 'DtMF' Dominates Hot 100 with Chart-Topping Power!

A recent 'Ask Billboard' mailbag delves into Hot 100 chart specifics, featuring Bad Bunny's "DtMF" and Ella Langley's "C...

Shakira Stuns Mexico City with Massive Free Concert Announcement!

Shakira is set to conclude her historic Mexican tour trek with a free concert at Mexico City's iconic Zócalo on March 1,...

Glen Powell Reveals His Unexpected Favorite Christopher Nolan Film

A24's dark comedy "How to Make a Killing" is hitting theaters, starring Glen Powell, Topher Grace, and Jessica Henwick. ...