The Strangers Next Door: A New Dilemma at Africa’s Threshold

When America Sends Them Back

In the hushed valleys of eSwatini, a quiet storm is brewing. News recently broke that the United States had deported dozens of African nationals—many of them Swazi-born or long exiled—and quietly housed them in the tiny southern African kingdom. The development, at first glance, seemed procedural. Nations deport people. Others receive them. But in a continent like Africa, where colonial borders bleed into every decision, and sovereignty is still a sensitive subject, the story is far from simple.

South African intelligence services have since raised concerns, not over the legality of the deportations, but over what lies beneath them. Who are these deportees? Are they just returnees, caught in the US immigration clampdown, or are they, as security chiefs suspect, carriers of other interests—criminal affiliations, technological surveillance tools, or international baggage far greater than their modest appearances suggest?

As whispers turn into questions, and questions into suspicion, we are once again drawn to an uncomfortable truth: Africa remains the recipient of other people’s decisions.

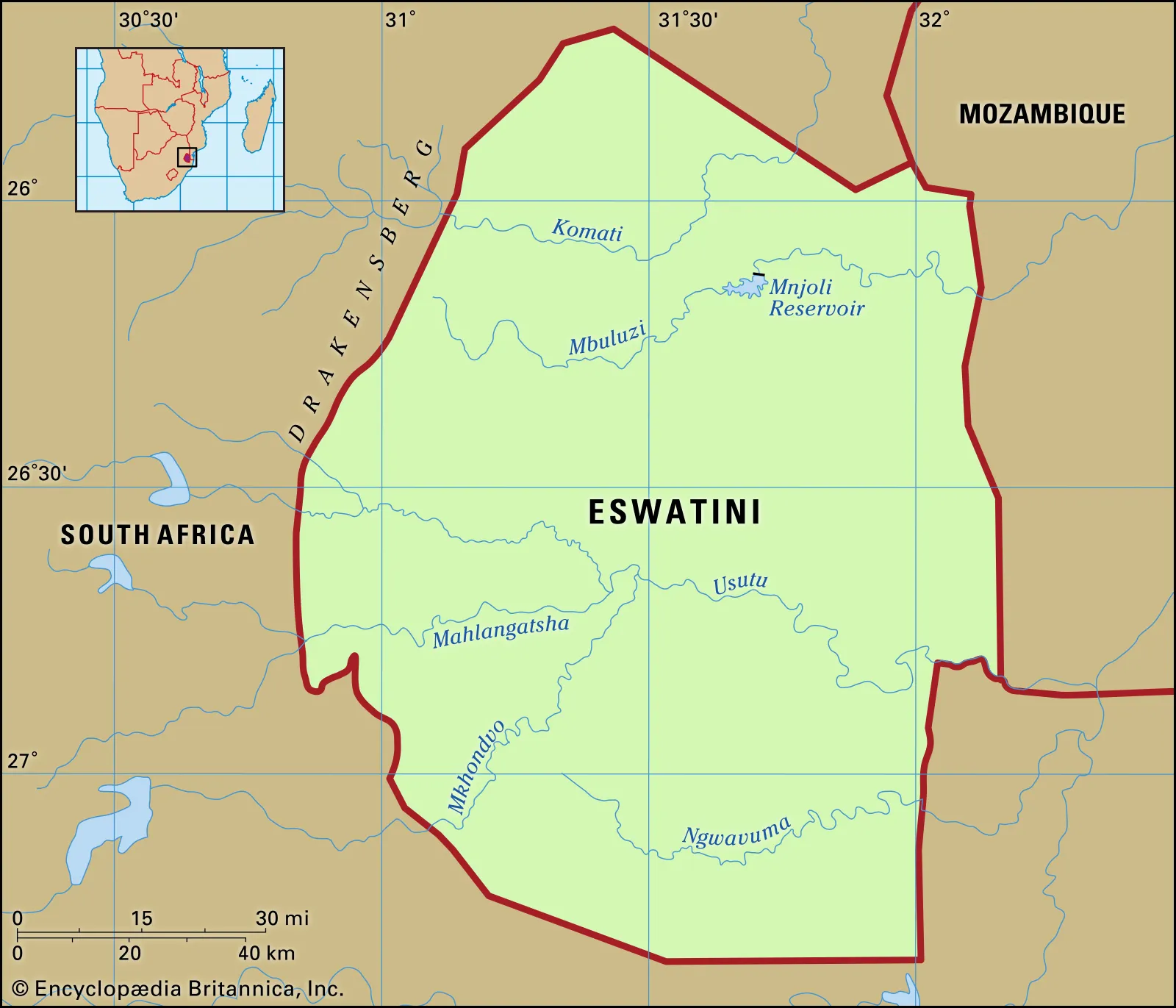

eSwatini: Between the Mountains and the Margins

SOURCE: britiannica

With its landlocked geography and monarchy-preserved governance, eSwatini often escapes the headline reels. To outsiders, it may seem a nation curled quietly in the folds of southern Africa, preoccupied with its own pace of modernity. But to its neighbors—especially South Africa—it is no less important than any strategic outpost.

eSwatini’s hosting of US deportees was not a publicized diplomatic gesture, nor the result of national policy debated in open parliament. It was, instead, a quiet transaction—silent enough to slip beneath international radars, but loud enough to rattle Pretoria.

And rattle it did.

South Africa, sharing long borders and even longer historical ties with eSwatini, immediately demanded clarification. Who approved the arrivals? What were their backgrounds? Why eSwatini? And more pressing—was this a one-time decision or a new pattern being tested on African soil?

The answers remain elusive. But the implications do not.

Sovereignty and Soft Power: An Unequal Exchange

When nations like the United States deport foreign nationals, there is an expectation that they are returned to their countries of origin. What made this case distinct was not just the lack of transparency but the apparent outsourcing of responsibility. It begs the question: Why would a country thousands of miles away deposit its immigration residue in eSwatini?

The answer, as with many African dilemmas, lies not in law but in leverage.

The quiet truth is that many African states, including eSwatini, are tethered to Western aid, trade preferences, and geopolitical favors. In moments like this, sovereignty is not always about what a nation chooses to do—but what it dares not refuse.

Diaspora Connect

Stay Connected to Home

From Lagos to London, Accra to Atlanta - We Cover It All.

If eSwatini was asked—or pressured—to accept deportees under some bilateral understanding, it would not be the first African country made to accommodate foreign interests under the guise of cooperation. From hosting foreign military bases to allowing experimental medical trials, the continent has long been the testing ground of foreign anxieties.

But housing deportees—especially those flagged with criminal associations—is not a harmless decision. It carries risks, not just of social integration but of national security, cross-border crime, and the further erosion of African autonomy.

Strangers on the Border: South Africa’s Unease

For South Africa, which has long struggled with undocumented migration, cross-border syndicates, and delicate diplomatic relationships, the sudden presence of US-returned individuals in neighboring eSwatini feels more like a provocation than an accident.

Pretoria’s response has been sharp and public. Intelligence agencies are monitoring the movements of these individuals, and internal memos warn of a potential surge in organized crime and foreign influence. Already, some Swazi and South African residents alike are questioning who exactly these returnees are—and why no public record exists of their deportation.

SOURCE: gettyimages

More than security, though, the incident speaks to a broader fear among African states: the fear of being outmaneuvered in a world that rarely gives them the benefit of equal partnership.

A Continent Still Negotiating Its Borders

What makes this episode even more complex is the irony of African borders. The deportees housed in eSwatini are said to be Swazi nationals, but many had lived abroad for decades—some since childhood. Their ties to eSwatini are fragile, and their reintegration is uncertain.

Yet, like many postcolonial states, eSwatini lacks the bureaucratic muscle to challenge deportation decisions made in Washington. So it becomes the reluctant host, forced to absorb lives shaped elsewhere.

The broader African reality is this: postcolonial states still operate within frameworks they didn’t design. Whether it is migration law, extradition treaties, or trade policy, African countries are often reacting to global decisions rather than initiating them.

So, when foreign powers decide to return their undocumented immigrants, the question of reintegration—of identity, of documentation, of legality—is not one asked by the deporting nation. It is answered, painfully and awkwardly, by the receiving one.

The Human Layer: Exiles and Returnees

Beneath the diplomacy and suspicion lies a deeply human story. These deportees, regardless of what they’ve been accused of, are still people. Many of them were uprooted from familiar systems, reclassified as illegal, and expelled to a country they barely remember. Their reentry into Swazi society will not be seamless.

There will be tension. Some may face rejection. Others may fall into darker patterns—especially if jobless, homeless, and stripped of the right to rebuild.

eSwatini is no stranger to poverty and unemployment. Adding returnees with fragile support systems may only worsen the social fabric. Without a robust plan for reintegration—education, healthcare, psychological support—these returnees risk becoming a problem rather than a priority.

And if that happens, Africa loses twice: first, by hosting a burden it didn’t ask for, and second, by failing to reclaim its own.

Whose Decision Is It, Really?

This case forces Africa to ask a fundamental question: who decides who comes and who stays?

Diaspora Connect

Stay Connected to Home

From Lagos to London, Accra to Atlanta - We Cover It All.

SOURCE: gettyimages

If deportations like this continue—silent, sudden, and secured behind diplomatic curtains—then the continent may find itself on the receiving end of global excess. Not just migrants, but also policies, debts, and digital surveillance.

eSwatini’s quiet compliance may soon become a blueprint. Other nations, weaker or more beholden, could be asked to host deportees, refugees, or even military outposts in exchange for aid. That trade may not be officially acknowledged—but it is real.

And in that trade, sovereignty becomes a commodity.

Between Silence and Sovereignty

There are no easy answers to the situation unfolding in eSwatini. But silence, as always, is dangerous. If African states do not collectively define the terms of engagement when it comes to deportation, migration, and international influence, then the future will be defined for them.

South Africa’s concern is valid. eSwatini’s position is precarious. And the deportees themselves are caught between policies and prejudices, uncertain of where home truly is.

As always, Africa must look within. The continent cannot afford to simply absorb the world’s leftovers—its debts, its deportees, or its discarded responsibilities. To do so would be to accept a future written by others, in which African agency is the first casualty.

eSwatini may be small, but the question it raises is enormous: when others choose for us, do we still govern ourselves?

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...